The story of the Caucasus Germans is one of survival, innovation and tragedy. It is undoubtedly fascinating yet surprisingly unknown, even in Germany, which makes a recent exhibition there all the more noteworthy.

Beyond Borders: Germans searching for a home between Württemberg and the Caucasus is part of a series of events being held across 2017 and 2018 to celebrate 200 years since Swabian Germans first settled in the South Caucasus. Shortly after the exhibition’s launch near Frankfurt in July Visions was grateful for the opportunity to correspond with Professor Dr Eva-Maria Auch, an expert in the Caucasus Germans and chairman of the society EuroCaucAsia.

VoA - How did you become interested and involved in the topic of the Caucasus Germans?

EMA - It’s a long story. During my Oriental Studies course in the 1970s I was already hearing repeated mentions by Azerbaijani fellow students and lecturers of the German traces left in Azerbaijan. However, the area around Kirovabad (today Ganja) was closed to foreigners and so a visit to the former German settlements was not possible at that time. After gaining my doctorate in the mid-1980s I was looking for a new research topic. The South Caucasus really interested me in the context of Enlightenment movements in the Near East. But here, too, archives needed for an investigation into the role of Islam were closed. So I turned to the topic “Caucasia in German-Russian relations,” and was able to carry out research on this in archives in Germany, Azerbaijan, Russia and Georgia. The outbreak of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict was then a further decisive point: flight; expulsion; reconciliation – central topics in German history – became a painful reality for over one million citizens of Azerbaijan. I was now indeed able to visit the former German settlements and was deeply impressed by the respectful treatment of the German heritage, but at the same time it became clear that the refugees who had been resettled in the Ganja region would know nothing at all about the German traditions. It was a very difficult situation: on the one hand the great need of the refugees for housing demanded the rebuilding and extension of the houses, on the other hand the German cultural heritage needed to be preserved. The latter was achieved with the support of the Azerbaijani government and in cooperation with Azerbaijani academic experts, creative artists as well as the German community and the German embassy in Baku. In 1997 we held the first international conference in Helenendorf/Khanlar/Goygol (Helenendorf was renamed Khanlar and then Goygol – Ed.) and there is an increasing openness in Azerbaijan towards recognising this common history and sensitivity towards the preservation of the German cultural heritage. Professor Dr Eva-Maria Auch at the launch of the exhibition at the Kunststation Kleinsassen art gallery, July 2017. Photo: courtesy of Professor Dr Eva-Maria Auch and EuroCaucAsia

Professor Dr Eva-Maria Auch at the launch of the exhibition at the Kunststation Kleinsassen art gallery, July 2017. Photo: courtesy of Professor Dr Eva-Maria Auch and EuroCaucAsia

How did the German public react to the exhibition’s launch at the Kunststation Kleinsassen art gallery? Is it a topic that is widely known in Germany?

The exhibition Beyond Borders: Germans searching for a home between Württemberg and the Caucasus is the first one to be dedicated explicitly to the history of the Caucasus Germans. With approximately 50,000 people deported in October 1941, the South Caucasians were a relatively small group among all the Germans in Russia/Soviet Union. Many exhibition visitors knew nothing about the history of the Caucasus Germans, others were pleased that this chapter of history had at last been addressed. A special feature of the Kleinsassen art station was that Azerbaijan could be presented within a varied cultural context, and our part of the exhibition was able to provide a direct reference point. With this chapter from German-Azerbaijani relationships in the past, visitors gained direct access to the Azerbaijan of today, where there is not only a justifiable pride in religious tolerance and multi-ethnicity, but also a recognition of this as something to be valued in facing the challenges of our own time.

Did any Caucasus Germans or their descendants attend?

Yes, of course. In our cultural and scientific EuroCaucAsia Society, which initiated the project, not only are former Helenendorf residents involved, but we also displayed the exhibition in Reutlingen at the annual meeting of people from Helenendorf and Georgsfeld. Dr Ohngemacht organised a showing in Göppingen, and Ms Rasper is looking for an exhibition venue in Eppstein/Frankfurt in the autumn. So descendents of the “Azerbaijani Germans” are actively involved in the presentation of the history of German-Azerbaijani relations.

A map showing the migration route taken by the original Swabian settlers. Photo: courtesy of Professor Dr Eva-Maria Auch and EuroCaucAsia

A map showing the migration route taken by the original Swabian settlers. Photo: courtesy of Professor Dr Eva-Maria Auch and EuroCaucAsia

1817: GERMANS IN THE CAUCASUS

The story of the Caucasus Germans begins in 1817. In September of that year 31 families from Württemberg arrived in Tiflis. By 1819 over 2,500 settlers had reached the South Caucasus and seven other colonies had been founded between Yelizavetpol (today’s Ganja) and Tiflis. The precise reasons for their emigration aren’t fully clear but, generally speaking, from the Russian side German settlement meant an increased Christian presence in the south and a potential economic boost, while for the Swabians it was an opportunity to escape the economic and political upheaval of the Napoleonic Wars and the great famine of 1815-17.

One important aspect brought to light in the exhibition is the religious factor, since many of those migrating to Russia and the South Caucasus came from pietist areas and were profoundly devout. Indeed, the Lutheran church lifestyle remained the integrating force for the social and cultural life of the German settlers right into the 20th century.

How easy was it for them to set up home in the Caucasus and what challenges did they face in the early years?

The settlers came into a territory having totally different climatic and socio-geographic conditions. They were wine growers and craftsmen, but first of all they had to survive: find clean drinking water, build accommodation for themselves and their animals, cultivate fields and gardens. Starvation and epidemics were the greatest dangers, alongside a tense political situation. Numerous families died out completely. So it is that this development has been described in symbolic terms with the saying: ‘‘the first generation have death, the second are in need, the third have bread.’’

Whilst for the colonies in the 1820s it was still a case of simple survival, the situation gradually stabilised during the 1830s, when the number of births exceeded the number of deaths. From the middle of the 1840s the settlers seemed to have adjusted to their new circumstances. The specialisation in agricultural products and increasing sales opportunities in the second half of the 19th century led to economic improvement.

Harvesting grapes involved inviting the inhabitants of the settlements and their neighbours of all ages to offer their labour for the task. Photo: courtesy of Professor Dr Eva-Maria Auch and EuroCaucAsia

Harvesting grapes involved inviting the inhabitants of the settlements and their neighbours of all ages to offer their labour for the task. Photo: courtesy of Professor Dr Eva-Maria Auch and EuroCaucAsia

This period also saw the expansion of the wine industry, led by two families – the Vohrers and the Hummels, for which the Germans are widely remembered in the Caucasus to this day. At the same time in nearby Gedebey another entrepreneurial German family, the Siemens brothers, were mining for copper and gold.

As their economic situation improved the Germans began to feel increasingly at home in the Caucasus, integrating those aspects of the local culture they deemed necessary or useful while also introducing European methods to the locals.

To what extent did the colonists assimilate into the local culture or, on the contrary, manage to preserve a distinct German identity?

Whether one can speak of “assimilation” into the local culture is hard to say. But it has become clear that the general nationalistic paranoia before the First World War was also a challenge to the Germans in the Caucasus. Russification led to a counter-reaction. People were more conscious of their “German roots,” married girls from Germany, went there to study, travelled more often to the “old homeland,” subscribed to newspapers and magazines, founded the Caucasian Post/Kaukasische Post, organised themselves in “German Associations” etc. Despite this they regarded themselves as loyal, became Azerbaijani citizens, worked in the first parliament of the Azerbaijani Democratic Republic (ADR), and then became Soviet citizens. Indeed, in the 1920s the colonists’ strong sense of community became the basis for a flourishing economic and cultural period with the establishment of the Konkordia cooperative.

Following the 1929 “law on religious affairs” the Evangelical-Lutheran church in Baku became a workshop for the construction of a statue of Bolshevik leader Sergey Kirov. Photo: Azerbaijan State Archive for Film and Photography

Following the 1929 “law on religious affairs” the Evangelical-Lutheran church in Baku became a workshop for the construction of a statue of Bolshevik leader Sergey Kirov. Photo: Azerbaijan State Archive for Film and Photography

1941: WAR & DEPORTATION

For the Caucasus Germans, 1941 signaled separation for many years, if not forever. Immediately after the German attack on the Soviet Union all Germans in the Caucasus were classified as potential enemies and deported to various regions of Kazakhstan.

When and how did the situation begin to deteriorate for the Caucasus Germans?

In the first phase of sovietisation, in the times of the so-called “korenizatsiya” (nativisation) the settlements were able to relax for one last time, even though we know today that not only were the large-scale wine producers regarded as exploiters, and dispossessed of their property, but that the Germans (like other ethnic groups, e.g. Azerbaijanis from Iran) had already been classified as “untrustworthy” by the so-called Stalinist repressions of 1937-38.

There were arrests and trials in 1926, 1930, 1933 and 1935, which affected about 15 per cent of the German inhabitants of the colonies. In 1935 alone 600 families from Annenfeld and Helenendorf were forcibly deported to East Karelia on a charge of espionage. Since the 1920s German pastors had already been persecuted and in December 1934 a renewed wave of arrests took place. In 1936-1937 the churches were eventually closed as spiritual centres and in 1938 there followed an enforced reorganisation of school education in the colonies.

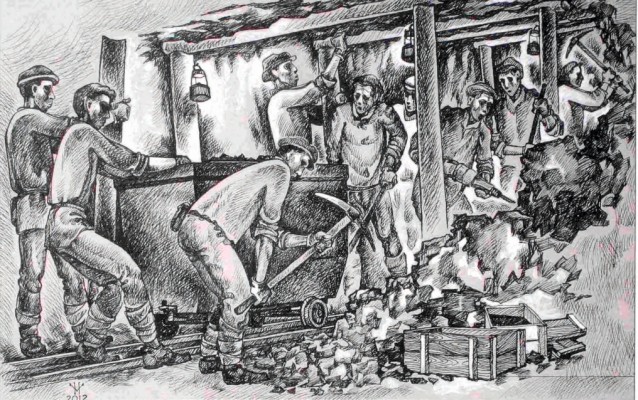

Following deportation, between 1941 and 1946 most ethnic German men, as well as many women, worked in forced labour camps where highly physical labour included tree felling, coal mining and railway construction. Malnutrition, sickness and death were common. From 1946 forced labour was gradually removed and some were allowed to reunite with their families, but any hopes of a return following the Second World War proved illusory.

Did any of them ever return to the Caucasus? Where are their descendants now?

The right of return remained limited and was only lifted with a decree of the Supreme Soviet on 3 November 1972. Up to 1979 there were 2,053 Germans deported from Georgia who returned.

Despite this, there is still a German community in Baku today. This is however often a case of the families of specialists needed in the petroleum industry, or the descendants of those German women married to non-Germans, who were given the right to remain. Those from the rural settlements of Azerbaijan who survived their time in Kazakhstan mostly emigrated to Germany in the meantime, where they live mainly in Baden-Württemberg.

A separate chapter in the story of the Germans in the Caucasus, also addressed in the exhibition, are the many POWs brought to help reconstruct Soviet industry and urban centres following the Nazi capitulation in the Second World War.

Can you describe the experiences of German POWs in Azerbaijan; is their legacy still visible here today?

I think that in Baku itself there are traces that cannot be ignored: the government building on Azadliq Square is regularly associated with the German prisoners of war. I was recently able to visit the newly renovated headquarters of the Azerbaijan State Railways, on which the prisoners of war also worked when it was built. A retired German teacher sent me a picture he had drawn of the Mingachevir dam and a report about his time as a prisoner of war. Another man had been deployed to Dashkesan; a grandson was looking for traces of his grandfather who had worked and died in Salyan... There are many such examples of those who were persecuted under the Soviet system. Prisoners of war were often part of the inhuman Gulag system, in which even full citizens of the Soviet Union had to carry out forced labour – war and totalitarian violence know no nationality – and this needs to be remembered.

One of two cemeteires for German prisoners in the former village of Helenendorf. This was also the site of a hospital. Photo: Eva-Maria Auch

One of two cemeteires for German prisoners in the former village of Helenendorf. This was also the site of a hospital. Photo: Eva-Maria Auch

2017-18: 200th ANNIVERSARY

Since its launch at the Kunststation Kleinsassen in July, Beyond Borders has travelled across the Caucasus with showings in Baku, Goygol, Bolnisi and Tbilisi.

What is being done to preserve the German legacy in the Caucasus and why is it important to do so?

The 200th anniversary of the German migration to the South Caucasus is not just intended to bring information to a wider public both at home and abroad about the economic and cultural achievements of these people, but above all to offer a reflection on the causes and effects of migration, flight, expulsion, intercultural exchange, making oneself at home, and the delineation of boundaries, and to make references to current crisis situations in the region and within Europe. This means that it is in no way a glorification of a German hard work ethic, but what is much more important to us are questions that are of highly topical and universal significance: why do people leave their ancestral homeland, what do flight, expulsion, migration actually mean for the communities left behind and for the host communities receiving them, as well as for the families and the individuals themselves? What is the significance of the loss of a homeland and putting down roots in another? Our exhibition is meant to stimulate thinking about such questions and discussions about them. In this respect refugees and those forcibly displaced by the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict should and would be able to identify with their own destinies in this exhibition.