This article first appeared in Russian newspaper Nezavisimaya Gazeta on 25 April 2017. Visions has kindly been granted permission to translate and republish it. The accompanying photographs were chosen by Visions and did not appear in the original article.

Why did the USSR collapse? What was the impetus and trigger for this geopolitical cataclysm? Which individuals and organisations sought to profit from the wreckage of the state? These questions still torment millions of people, and it is important to answer them in order for today’s Russia to be able to withstand multiple blows.

Unlike the Roman, Byzantine or Austro-Hungarian empires, the USSR was not defeated in any global armed conflict or war. Obviously, isolated local ethnic conflicts could not lead to the disintegration of a huge super-state. There were internal reasons which, through the efforts of certain people, evolved into bloody conflicts. It should be acknowledged that they were kindled and maintained in every possible way by a certain part of the ruling Soviet elite. The lessons of that period are important for any multinational country, and above all for modern Russia.

US president Ronald Reagan and vice president George H. W. Bush meeting Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev on Governor’s Island, New York, 7 December 1988, the same day a terrible earthquake struck the Armenian city of Spitak. Photo: US National Archives/Wikimedia Commons

US president Ronald Reagan and vice president George H. W. Bush meeting Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev on Governor’s Island, New York, 7 December 1988, the same day a terrible earthquake struck the Armenian city of Spitak. Photo: US National Archives/Wikimedia Commons

1987 was a landmark year for the world at large. The USSR proclaimed a policy of glasnost and a plenary session of the Central Committee decided to hold alternative elections to the Councils of all levels. The young Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev was applauded by the whole world, Soviet-American relations were rapidly improving and freedom was felt in the air.

Meanwhile, in the small world within the USSR old ethnic conflicts which seemed to have been securely hidden “under the rug” by the government began to make themselves known.

The first blow to the unity of peoples was dealt in Nagorno-Karabakh (NKAR), an autonomous region within the Azerbaijani SSR with a predominantly Armenian population. Karabakh became the trigger for all subsequent conflicts and, as is rightly noted in the foreword to the book by British journalist Thomas de Waal Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War, it became the first conflict that stirred Gorbachev’s Soviet Union. Then began clashes between Georgians and Abkhazians, pogroms of Meskhetian Turks in Uzbekistan, clashes between the Uzbeks and Kirghiz. It was these events that made possible the subsequent “parade of sovereignties” of the Soviet republics.

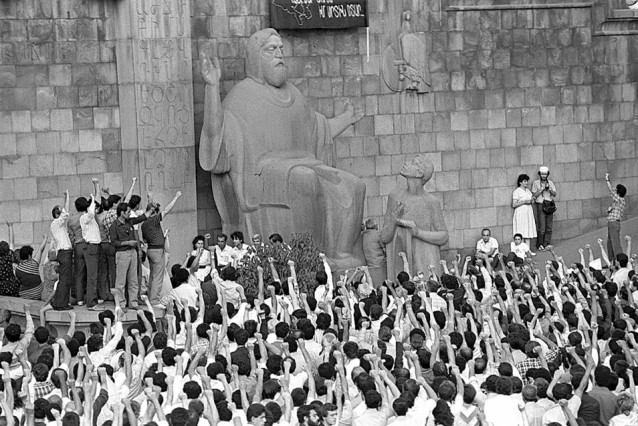

But the first large-scale nationalist movement began in Nagorno-Karabakh. What happened there? The disruption of peace on the ancient Karabakh land, where Armenians and Azerbaijanis had lived peacefully from time immemorial, began in 1987 when the Karabakh Committee, comprised of various disparate public and political groups, was set up in Yerevan. This set as its goal the struggle for the secession of Karabakh from the Azerbaijani SSR and the transfer of this autonomous region to the Armenian SSR.

The standard of living in Nagorno-Karabakh was significantly higher than in the neighbouring regions of Azerbaijan and Armenia. However, the nationalist activists putting forward beautiful slogans were little concerned by the fact that their actions would condemn people to bloodshed and poverty. It often happens that protests are staged by those who live not worse but better than others. And then they lose what they have. This is what happened in Karabakh – nowadays people in the autonomous region are much poorer than the average, both in Azerbaijan and Armenia.

Karabakh Committee rides the wave

The members of the Karabakh Committee were respected people, among whom were teachers, journalists, scientists and even academicians. However, neither their academic scrupulousness nor their journalistic impartiality prevented them from throwing themselves into the rage of a revolutionary struggle which a year later led to cruel and bloody events.

A key member of the Karabakh Committee, Igor Muradyan, was a research fellow at an economics institute and worked at the State Planning Committee of the Armenian SSR. It is worth noting that Muradyan himself underwent a cycle of changes – from a Gorbachev democracy activist to a nationalist and today he calls Armenians “slaves of Russia.” In an interview with Thomas de Waal Muradyan frankly admits that supporters of the referendum did not care about the opinion of the Azerbaijanis living in Karabakh: We weren’t interested in their fate back then and we aren’t interested in it now. At the same time, Azerbaijani representatives were described as “instruments of power.” And this is also an important conclusion: those who begin to destroy a country with protests first pretend to be patriots. But time shows that they were traitors from the very beginning.

Another common feature of destroyers, which later entered the textbooks on how to organise “colour revolutions,” is the combination of pro-Western and nationalist ideas. It is easier for puppeteers to deceive people with the help of nationalism.

One of the members of the Karabakh Committee, the mathematician Vazgen Manukyan, later admitted that the idea of democracy could not raise the wave by itself. It was possible to “raise the wave” with the idea of transferring Karabakh to Armenia, which loosened the seemingly formidable Soviet state, poorly bound as it was.

The first strikes demanding the secession of Karabakh in October 1987 were staged in the NKAR by students egged on by nationalists. On 20 February 1988, a session of the regional NKAR Council appealed to the Supreme Council of the USSR and the Supreme Council of the AzSSR with a request to transfer the region to Armenia. On the same day, rallies of thousands of people were held in Stepanakert and Yerevan in support of this initiative. The organisers succeeded in fomenting clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis. What became grief for thousands of families was a success for the destroyers.

At the same time, the idea of a “referendum” was put forward and a member of the Karabakh Committee, the writer Zori Balayan, was an active gatherer of signatures to support it. An intellectual and defender of Baikal who worked as a doctor in his youth, Balayan forgot about the main principle of medicine – do no harm. The ideas of independence for Karabakh shook the foundations of inter-ethnic peace, frail as it was, opening the way for open and bloody hostility between peoples.

The Karabakh activists gathered 80,000 signatures and submitted them to the Central Committee of the CPSU, hoping for the support of the sympathetic “Armenian lobby.” And their hopes for betrayal at the top of the Soviet regime were justified. The adviser to USSR president Gorbachev, Abel Aganbegyan, turned out to be more an Armenian nationalist than a communist and statesman. At a crucial moment, he supported his own nation, not the unity of the country. Aganbegyan said in an interview with the French communist newspaper L’Humanite that he would like to see the return of Karabakh to Armenia. As an economist, he believed that the ties between Armenia and the NKAR were better than those between the NKAR and Azerbaijan.

These irresponsible words of a person who was primarily supposed to deal with issues relating to the Soviet economy, not ethnic relations, were noticed all over the world, and although the Central Committee tried to assure the Azerbaijani side that this was Comrade Aganbegyan’s “personal opinion,” “it left an aftertaste.” The alarmed Politburo understood, in the words of Gorbachev, that “the process has begun,” but was afraid to take action fearing even worse events.

And if in Gorbachev’s team it was Aganbegyan who helped the country’s destroyers, in Boris Yeltsin’s team hatred between Armenians and Azerbaijanis was incited mostly by the deputy of the USSR Supreme Council, Galina Starovoytova. She provided active assistance to the Karabakh Committee. An activist of the democratic movement, she knew Karabakh well during its calm and peaceful times and often went there as an ethnographer, studying the phenomenon of local centenarians.

Starovoytova became one of the main champions of independence for Karabakh. Did she realise that in doing so she was actually undermining the foundations of the country? Well-known human rights activist Svetlana Ganushkina later wrote in the magazine Vlast that at one of the meetings of Moscow democrats dedicated to Karabakh in the mid-1980s Starovoytova said that Christianity is a democratic religion but Islam is undemocratic. I think these are the words not of a democrat, but either of someone who incites enmity or of a provocateur. Starovoytova acted as the link between the Karabakh Committee and a group of Russian democrats led by Yeltsin.

The words thrown into the crowd reached their goal – tired of Soviet party meetings and speeches, people listened to their new democratic idols, not understanding that playing with ethnic problems in a multiethnic country would lead to its death.

In an interview with the Russian media, Manukyan, who later became Prime Minister of Armenia, admitted that although he dreamed of Armenia’s independence, he did not think he would live to see the collapse of the USSR: It seemed to me that only the next generation would see an independent Armenia, while our generation should see a reformed socialism within the framework of the Soviet Union. Only in 1988, with the appearance of the Karabakh movement in Armenia, we began to feel that we could gain independence.

While the Union’s centre was stuck in endless talking and “procedural issues,” the influence of the Karabakh Committee grew, and in March 1988, to help it, the Armenian public and political organisation, Krunk, was set up. The organisation declared as its goal the study of monuments of the culture and history of Armenia, but its real purpose was the political struggle for the secession of Karabakh from Azerbaijan and of Armenia from the USSR. Krunk became the first organisation in the USSR which began to use strikes as a weapon. The core of Krunk, like that of the Karabakh Committee, was the intelligentsia, and the main ideologist was the future Prime Minister of Armenia Robert Kocharyan.

We all loved Georgian movies, admired the precision of the Balts, the hospitality of the Ukrainians and Belarusians, supported each other’s football teams and toured the sights of the ancient cities of Central Asia

The head of Krunk was the director of a local building materials factory, Arkady Manucharov, who ironically in the Soviet years had been awarded the Order of Friendship of Peoples. I am convinced that he betrayed this order when, as a politician, he became a champion not for the friendship but for the enmity of peoples. It is possible that this award might seem rather officious today, but many of those who lived in those years remember not the officious names of orders and slogans that tired them to death, but the real friendship that bound many people together in the then USSR.

We all loved Georgian movies, admired the precision of the Balts, the hospitality of the Ukrainians and Belarusians, supported each other’s football teams and toured the sights of the ancient cities of Central Asia. We were different, spoke different languages and belonged to different cultures, but we were united and bound together not by the sermons of leaders or the demonstrations of workers. It was something more – interethnic marriages, the common past – great and tragic, hostility towards nationalism and the victory of 1945.

Nationalism was thus unleashed, and the consequences of this were devastating – marriages and families fell apart, people were engulfed with mutual hatred, and yesterday’s soldiers of a once united army looked at each other through the sights of machine guns.

A homemade rocket launcher belonging to Azerbaijani forces in the village of Erkech fires at enemy positions in Todan village, Goranboy district, Azerbaijan 1993. Photo: Oleg Litvin

A homemade rocket launcher belonging to Azerbaijani forces in the village of Erkech fires at enemy positions in Todan village, Goranboy district, Azerbaijan 1993. Photo: Oleg Litvin

The struggle of those supporting the separation of the NKAR from Azerbaijan led to sad consequences. The feuding did not bypass the village of Tug in the south of Karabakh which was home to many mixed families. People of different nationalities who had lived side by side for years told visitors that the hostility would not affect them. However, already by September 1988 a border between the Armenian and Azerbaijani parts of the village had been drawn. Symbolic of the tragedy was the story of one large family: the Azerbaijani husband stayed on one side with three children and his Armenian wife on the other, also with three children.

Meanwhile, the situation in Karabakh deteriorated. Enterprises where numerous rallies of supporters of the transfer of the autonomous region to Armenia were held came to a standstill.

Emotions and reason did not help

In order to demonstrate the Union’s position once again, in March 1988 an article was published in the main mouthpiece of the CPSU Central Committee, the newspaper Pravda, under the headline Emotions and Reason. On the events in and around Nagorno-Karabakh. Its goal was to cool down the hotheads on both sides of the conflict. The article, in which each word was weighed carefully, was jointly prepared by three Pravda employees of different nationalities – special correspondent Georgy Ovcharenko, correspondent for the Azerbaijan SSR Zaur Kadymbekov and correspondent for the Armenian SSR Yura Arakelyan.

However, the publication received a hostile reception. Things reached a point where people started to burn whole piles of the Pravda issue right in the streets and shouted insults at me, the editorial office and Arakelyan himself, Ovcharenko said in a later interview.

The Karabakh Committee continued its destructive work even when Armenia itself was trying to cope with the severe consequences of the earthquake in Spitak, and the whole of the USSR, including Azerbaijan, came to the aid of the republic. Outraged by the behaviour of the Karabakh Committee, Mikhail Gorbachev, at a meeting with representatives of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Armenia in December 1988, accused members of the committee of spreading provocative rumours. For example, the republic was disturbed by reports that Armenian children would apparently not return home from Russia where they lived in families, and that all Armenians would allegedly be relocated to the Krasnoyarsk region.

Prime Minister of the Union’s government Nikolay Ryzhkov recalls that supporters of the separation of Karabakh went as far as blocking vehicles with construction equipment from Azerbaijan coming to the aid of earthquake victims. I just want to remind you that grief has always brought people together in all corners of the world. If there was no peace, there was at least a truce. In our “corner,” the disaster was used to make things even more painful, he wrote in his memoirs.

It is worth noting that even Gorbachev’s worst enemy, General Albert Makashov, showed solidarity with the president of the USSR in assessing the actions of the supporters of independence for Karabakh during the rescue operation. The terrible earthquake didn’t calm, but only spurred on the separatists, wrote Makashov, appointed commandant of Yerevan during the rescue operation. In his memoirs, he justly calls the Karabakh issue a lever for the loosening of separatist passions in the region. The general, in the book of his memoirs, The Tragedy of the USSR, recalls the peaceful life of Armenians and Azerbaijanis in Karabakh in Soviet times: They lived well and competed only in terms of who had the better wine and the tastier bread.

It was Makashov who, by the will of fate, arrested the leaders of the Karabakh Committee in December 1988. True, they were later released under pressure from the “Moscow public.” Among those arrested was the future president of Armenia, Levon Ter-Petrosyan.

Soviet Prime Minister Nikolay Ryzhkov, who did a lot to combat the consequences of the earthquake in Spitak, recalled with indignation that members of the Karabakh Committee were saying that the disaster was apparently caused by a bomb blast. The most unimaginable rumours were put forward by the movement and its Moscow allies to serve the destruction of a great multiethnic country.

The swallow that became a “Chicken Kiev”

Karabakh was the first swallow that foreboded the collapse of the country. As though having received the signal to act, in the different republics of the USSR popular fronts and national movements began to emerge, which were skilfully manipulated by the former “rosy Komsomol leaders” and teachers of Marxism-Leninism.

People’s aspirations of greater independence could have been understood if it were not for one “but” – in most cases the rallies stigmatised not the local or even Union party bosses, but ordinary people who came to the republics often not at the call of the heart, but for work or to restore the economy destroyed by the war. Despite being friends and good neighbours just yesterday, they started noticing the wry glances of those who only yesterday had invited them over and enquired about their children’s health. “Leave” was the softest word heard by those who only recently felt at least sympathy, if not love, for the republic in which they had to live, work and raise their children.

The Baltic Way was a peaceful demonstration on 23 August 1989 calling for independence for the Baltic republics. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Baltic Way was a peaceful demonstration on 23 August 1989 calling for independence for the Baltic republics. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Following the example of the Armenian nationalists, activists from opposition organisations in the Baltic republics demanded immediate independence. In August 1989, they organised a live chain from Tallinn to Vilnius in order to demonstrate their strength. Targeted attempts by the authorities of the USSR to suppress the uprising only made people even angrier. The central government did not offer an alternative – nobody wanted to live the old way, but the new way, which seemed bright and beautiful, turned out to be awful.

The fire lit in Karabakh soon engulfed the entire country.

Thirty years after the start of the confrontation, the conflict in Karabakh still continues. The renowned Armenian poet, Hovhannes Tumanyan, whose works are well known both in Azerbaijan and around the world, has a fairy tale about a drop of honey. It is about a hunter who returns from hunting with a dog and sees a small shop near the road selling honey. He asks the seller to pour some honey into a jar, a drop of honey falls to the floor and the owner’s cat starts licking it. Seeing the cat, the dog rushes and strangles it ... The owner of the cat kills the dog. The owner of the dog kills the owner of the cat and then a civil war begins. Today, this sad tale is still relevant, and most of all for Russia.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the beginning of those tragic events

A local conflict in Karabakh, which began with the separatist claims of Armenian nationalists and was accompanied by the forcible expulsion of Azerbaijanis from their lands, provoked a wave of bloody violence. The conflict was created and nurtured with the active participation of some representatives of the Soviet ruling elite as well as Western forces interested in weakening the country. It was not extinguished in time and became the ideal model for subversive movements throughout the Soviet Union, which eventually led to the collapse of a huge state. This year marks the 30th anniversary of the beginning of those tragic events. Our task is to learn from this recent tragedy, prevent it from happening again and not let nationalists and traitors destroy the country with irresponsible demands again.

About the author: Alexander Perendzhiyev is a Russian academician specialising in national security and combatting extremism. He has taught in the Department of Law at the Russian Academy of Economics named after G.V.Plekhanov since 2009, having previously served in the Soviet and Russian armed forces for over 22 years.