Any regular visitor to Azerbaijan can’t fail to be struck by the vast changes that have occurred in just a few years. Preparing the fifth edition of my Azerbaijan travel guide, the impact of the changes has been amplified all the more for me as I find just how much I need to cut and replace from the last (2010) edition. Looking back further to the very first edition (published 1999) it occurs to me that there is a story hidden away in all those now-outdated maps and drawings that I’ve deleted over the years. They might no longer be of use for a guidebook, but in a way their very removal seems to graphically illuminate Azerbaijan’s recent changes. And seeing them again gives the chance for a stroll down memory lane of the country’s erstwhile monuments and quirks.

All Hand Made

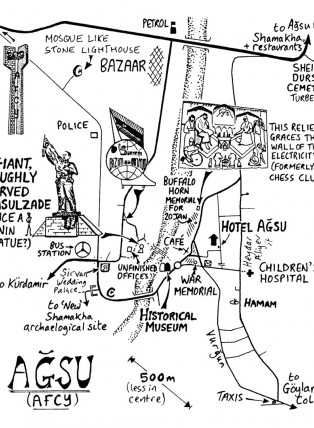

Given the Azerbaijan guide’s low publishing budget I couldn’t afford to include many photographs so I sketched my own illustrations in lieu. And lacking a professional cartographer, the pre-GPS era maps were hand-drawn, often based on simply walking streets or counting kilometres in a vehicle. Such map-making was not only laborious but often caused trouble with the local authorities who found the whole idea akin to spying. But this was the 1990s so a Soviet-era mentality was understandable. And as nobody had even imagined getting Google maps or Flikr photos on a mobile phone, my modest attempts were far from precisely accurate but were probably the best available for many towns and villages.

For years, spotting this distinctive bus shelter at Muxtariyyet was the easiest way of fi nding the access road to the Old Shamkir archaeological site. It has since been replaced by a less memorable if more practical new one

For years, spotting this distinctive bus shelter at Muxtariyyet was the easiest way of fi nding the access road to the Old Shamkir archaeological site. It has since been replaced by a less memorable if more practical new one

Sign Surrogates

In the late 1990s, driving around Azerbaijan was somewhat of a challenge. That was not just because many roads had become degraded into veritable assault courses, but also due to a serious absence of signage. Even those town markers that existed were mostly faded… and in Cyrillic script. Thus to help travellers to find more obscure sights, my book would note or illustrate whatever minor landmark might happen to lie at a key junction. Back before the start of the oil boom of the mid-2000s, one could count on very little changing year to year. So I had every confidence that marking, for example – House with red door – might still prove useful years later. Famously, on my map of Khinaliq, I said Old Men Sit Here as an orientation tool. Later I had comments from an incredulous reader saying that even five years later there really were old men sitting at that very point. Hopefully they had managed to sleep at some point.

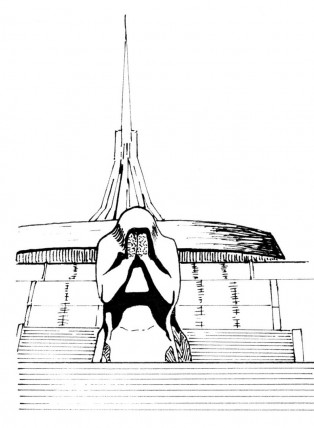

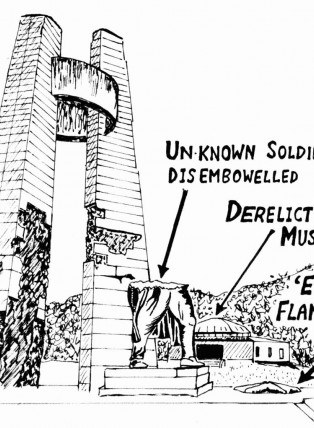

The 26 Commissars Memorial formed the centrepiece of what is now Sahil Gardens until 2009. When this picture was sketched, the individual commissars’ names had already been removed and the fl ame was no longer by any means ‘eternal’ due to irregular gas supply

The 26 Commissars Memorial formed the centrepiece of what is now Sahil Gardens until 2009. When this picture was sketched, the individual commissars’ names had already been removed and the fl ame was no longer by any means ‘eternal’ due to irregular gas supply

Disappearing Communists

Baku’s giant Kirov and almost all of Azerbaijan’s Lenin figures had been removed by the early 1990s. This was a shame for those Western tourists who still found a certain Cold War romance in seeking out old communist imagery. Fortunately certain other Soviet era figures remained. In Baku, impressive examples included the huge head of Transcaucasian leader Gazanfar Musabekov on Matbuat Circle (now supplanted by a flag), the expressive statue of Prokofi Dzhaparidze in Ganjlik (replaced since 2009 by a bombastic if comic-book Koroghlu figure) and the waving statue of commissar Meshadi Azizbeyov near what’s now the Beerbasha brewpub. He stood at a junction that is still widely known as Azizbayov Heyk even though Meshadi has long since turned into a fountain. Both Dzhaparidze and Azizbeyov (Azizbekov) had been amongst the 26 Commissars – leaders of the Baku Commune of early 1918 - who were later celebrated as Soviet martyrs. At the heart of Sahil Gardens (then known as 26 Commissars Square), all 26 were celebrated by a particularly memorable monument of a half-buried hero holding forth an eternal flame. In the Baku of the 1990s which had yet to imagine building the Flame Towers or Heydar Aliyev Centre, this monument counted as one of the city’s more major attractions.

Aghsu’s Rasulzade Statue

Before the extensive excavations of the now-fascinating ‘New Shamakha’ archaeological site, finding attractions in little Aghsu town was somewhat of a challenge. I did, nonetheless, find four minor curiosities whose sketches brought some interest to the Aghsu map in earlier editions of my book. All have since disappeared. The most intriguing was a giant statue of Mammad Amin Rasulzade (prominent figure in the 1918-1920 Azerbaijan Democratic Republic) tucked away amid some then-unfinished office buildings. Though locals that I asked denied it, I was convinced that the lower torso had been originally conceived for a Lenin statue.

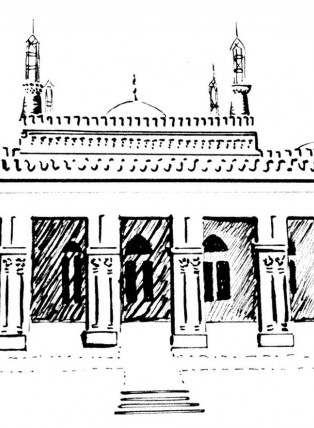

Shamakha’s Grand Mosque

Although Shamakha is one of Azerbaijan’s most historic cities, earthquakes and devastating invasions have ensured that almost no historical architecture remains. The one partial exception is the very distinctive mosque described in much of the literature as being the second oldest in the Caucasus. This date reflects its foundation rather than the structure itself and for the last four editions I included a drawing that showed the sturdy, low-slung style that it had essentially retained since the early 20th century. Renovations verging on a total rebuild had, by 2013, entirely transformed the mosque’s appearance inside and out though some original walls do remain from the ‘original.’

Drinking Spots Key

Early editions had a special icon for Soviet Atmosphere… the latter being the sort of place like Javid Café where - old men, proudly wearing their medals, breakfast over a maudlin shot of vodka and a sliced gherkin. Such places had been very common when I first visited Baku in 1995 but by the first edition were already getting rare enough to warrant inclusion as a cultural curiosity.

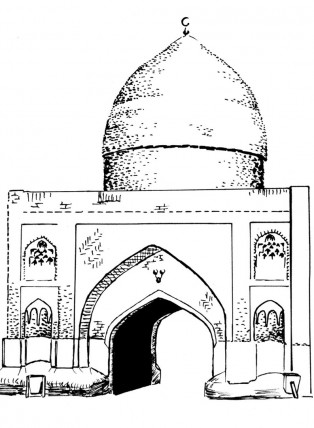

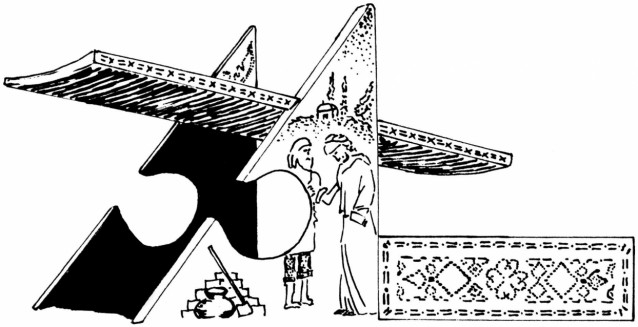

Ganja Imamzade

The Imamzade is the holiest Muslim shrine in Ganja, Azerbaijan’s second city, and once was the centre of a major fortified religious complex. However, while still attracting a trickle of the faithful, the site withered away over the centuries and especially during the Soviet era. By the time of my guidebook, the only really eye-catching architectural remnant was the brick portal and 1879 blue-tiled dome which I illustrated in the first four editions. Since 2008, however, a gigantic reconstruction project has been underway to transform the shrine into a major pilgrimage centre. Elegantly festooned with domes and patterned brickwork, the result (now almost complete) is one of Azerbaijan’s most impressive Islamic buildings.

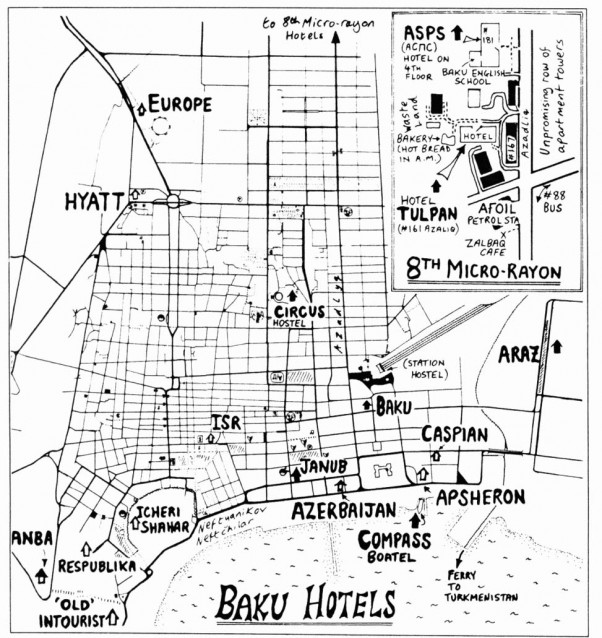

Baku Hotels Map

Of the hotels that feature on this fi rst edition 1999 map, only fi ve remain active today (three more have been demolished and replaced by brand new hotels on the same site). Can you spot which?

Of the hotels that feature on this fi rst edition 1999 map, only fi ve remain active today (three more have been demolished and replaced by brand new hotels on the same site). Can you spot which?

In the first edition of my book the accommodation available in the capital was so limited that I could make a half-page map showing all of Baku’s hotels. And that included an inset to help backpackers find a couple of last resort options way up Azadlyq pr. amid the tower apartments of the 8th Mikrorayon. These days you’d need more space than that just to show all the options in the Ganjlik suburb.

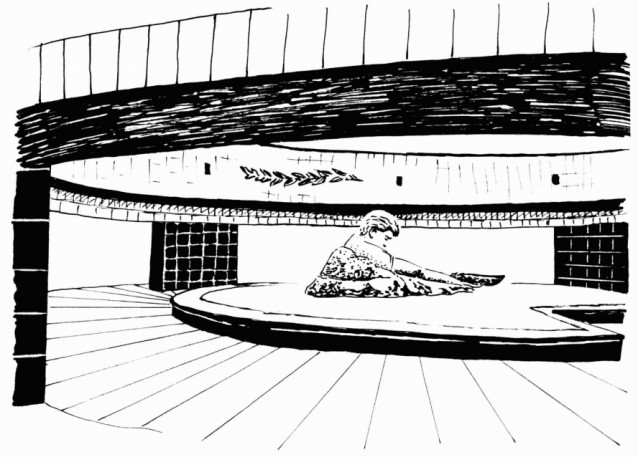

Nakhchivan’s Martyrs’ Mound

A hill that rises above the bus station has always been one of my favourite places in Nakhchivan City from which to get glimpses of Agridag/Mt Ararat floating on the western horizon. But like so much in Nakhchivan, the site has been entirely revamped in recent years. Where there was once a striking but fairly simple martyrs’ monument (hiding an almost invisible museum), there’s now a striking new Faxri Xiyaban (Alley of Honour) overshadowed by an even bigger flag park. And the same great views.

Fetching Water

In the 1990s many villagers still fetched water from springs using a giant 7kg copper vessel known as a guyum/jujum or a similar pot called a seheng. Over the years, direct water supply to rural homes has steadily improved but even in the fourth edition of my guide it was not uncommon to see women carrying jujums in areas of Lahic and Kish. These days both villages have fully piped water and many of the springs have dried up from lack of maintenance. Researching the fifth edition I did see one or two jujums still in use elsewhere but most are now in museums or form part of the décor for ‘ethno’ restaurants.

Balakan War Memorial

On my second visit to Azerbaijan in December 1997, I entered the country from Georgia and spent my first night in the small town of Balakan. The experience seemed to sum up the state of decay that provincial Azerbaijan was suffering in the early independence years. Back then, Balakan had just one decrepit hotel which was so cold that the manager advised me to go and buy wood in the bazaar and light a fire in my room… even though there was no fireplace. More emblematic still was the once-grand WWII memorial that had been left to rot on its prominent hillock at the eastern edge of town. Today that’s the centrepiece of a manicured park, the broken soldier figure replaced by a Heydar Aliyev statue backed by a mountain panorama and accessible on summer evenings by a cable car if you don’t want to walk up. And overlooking the park is a comfortable four-star hotel offering a very different welcome for arriving visitors.

About the author: Mark Elliott is a travel writer who has been covering Azerbaijan since 1995.The fifth edition of his guidebook is currently being edited for 2016/17 publication.