Ruslan Agababayev was born in Baku on 17 March 1976 into a family of doctors and musicians. Having enrolled in the piano classes of Olga Khomenchuk at the school named after Shahriyar (formerly named after Felix Dzerzhinskiy) he received an education in classical performance. Later, in 1994, he began studying at the Uzeyir Hajibeyli Baku Music Academy, in the piano classes of Professor Elmira Safarova. He then continued his education after moving to the US, at City College of New York, in the department of classical composition, under the tutelage of distinguished professor David Del Tredici – a famous composer in America, winner of the Pulitzer Award, and whos many musical compositions include a piece for the large mixed ensemble of Alice in Wonderland (Final Alice, 1976). At the same time he studied jazz with the pianist Bruce Barth, Mike Hollober and the famous double bassist Ron Carter, and then moved on to the composition classes of David Loeb at New School University, where he received his Masters degree.

Jazz is a form of inspiration that, when fed by the spark of traditional arts, draws the strength of its expression from common human passions and sufferings. In essence, the nature of jazz is folk and has unlimited possibilities for that special form of fantasy known as improvisation. Within improvisation lurks an idea, and a set of iridescent, tonal clues to a future more expansive concept.

Ruslan Agababayev’s creative development as a musician took place in a simple but very important environment – that of professional folk musicians, Azerbaijanis of Jewish origin from the village of Krasnaya Sloboda (Red Village) in Quba. Moreover, it wasn’t only his mother’s side of the family - the Yelizarovs, all professional folk musicians – that was blessed with musical ability, but also his father’s lineage, the Agababayevs, who had gained recognition as doctors. His father, Valeriy Agababayev, served as a military doctor for four years during the Karabakh War. Ruslan’s grandfather from his mother’s side, Khanuko Ilizarov (known as Khalyg), played the garmon (Azerbaijani accordion) and was the son of musicians, players of the accordion and zurna. His grandmother’s brother on his mother’s side, Semen Ikhizgilov, played the tar and his solo can even be heard in the musical Where’s Ahmed?. An uncle on his mother’s side, Robson Yefraimov, was renowned as a wonderful player of keyed instruments, and his aunt Tereza was also an accomplished mugham player on keyed instruments. However, as Ruslan recalls, his first steps into the world of music were made while spending time with his grandfather Khanuko.

And it’s with this interesting question that I would like to begin our conversation, a conversation which may be interesting and long-awaited for many; after all, Ruslan Agababayev hasn’t been seen on Baku’s jazz stages for over 20 years.

TM – Your musical talent is clearly genetic and it’s very important that there are ethno-musicians in your family. You grew up in a wonderful environment in which there was a special fondness for traditional arts, where family members not only listened to and cultivated all that was folk, but where there was also enlightenment, and this was naturally the initial foundation for your musical worldview. In your music one feels a very strong draw towards, or even a researcher’s interest in, different ethno-cultures, besides Azerbaijani. But did you study any ethno-musical cultures as part of your academic or jazz education? Your creative orientation is based on an ethno-style.

RA – This is, of course, an interesting question, which I should have asked myself. If I did study different ethno-music then it began with Azerbaijani mughams, I love this genre. In America I studied Latin jazz. But the issue here isn’t in the studying but more in the philosophy. The thing is that by nature I’m a humanist and a cosmopolitan, and I’m interested in different musical cultures. For example as a child I was interested in Indian music. My uncle and I watched and listened to Indian raga music and what John McLaughlin was doing. Although I don’t play raga, listening to it is very interesting. I also love Balkan music and have studied it a lot, from recordings. I also liked Moldovan tunes. Turkish and Arabian music are among my favourite cultures too. But my approach is different: I’m trying to take the thread of Azerbaijani music through all of these national genres, to connect the various ethno-colours with an Azerbaijani beginning. In fact, whatever I play (Balkan, Jewish music) I combine everything into one. For me there are no boundaries, I’m interested in the mixing of cultures. I’m interested in presenting Azerbaijani music to other cultures. For me this is very important and interesting.

Ruslan’s broad musical and professional interests are taking him on different missions. He is a member of ASCAP (American Society of Composers, Authors & Publishers) - a form of union of composers and musicologists in America, as well as a composer in residence of the Bachanalia Festival Orchestra, founded by renowned violinist Nina Beilina. Besides this, his mission as musical director of the organisation AZZEM (Azerbaijani Fraternity) is guiding him towards a very noble, enlightened aim – promoting Azerbaijani musical culture in America.

TM – What do people in America know about Azerbaijani jazz? Lots of musicians from the younger generation have gone to study there.

RA – Unfortunately, it’s still the case that little is known about Azerbaijan, Aziza Mustafazadeh is better known. Now, thanks to the fact that people are being sent here to study and go to festivals, there is more information about our musicians.

TM – Your work involves many different missions: as a composer, taking part in ethno-music festivals in Washington, working with the Bachanalia Orchestra, but central to your work is managing the cultural organisation, the Azerbaijani Fraternity. Could you tell me about the organisation’s work?

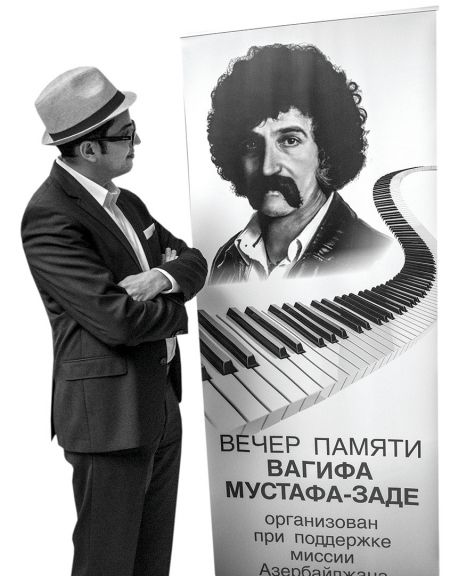

RA – In my work I try to pay great attention to my native Azerbaijani culture. Our organisation has held festivals dedicated to the music of Qara Qarayev and Vagif Mustafazadeh, to which both foreign and Azerbaijani musicians were invited. I also took part in these festivals and events. They were vibrant and generated great interest and admiration from the public. Among the guests were the composer and professor Khayyam Mirzazade and our great musician, pianist and dean of the Baku Music Academy, Farhad Badalbeyli.

TM – Recently there was a presentation of a book of poems by the great Azerbaijani poet Mohammed Hossein Shahryar, translated by contemporary Azerbaijani publicist, poet and artist Nobert Yevdayev, where parts of your cantata Heydərbabaya salam were also performed. For a jazz performer, such a sharp change in genres is remarkable, how did this come about?

RA - The idea to compose a cantata on such an interesting story was suggested to me by Fatma Abdullazade, Head of the Humanitarian Policy Department in the Azerbaijani Presidential Administration.

I was captivated by Shahryar’s beautiful poetry and found many things with a deep meaning for me – pain in the heart, homesickness, separation, the struggle with oneself.

In 2015 I came to Baku for the mugham festival, where my cantata Heydərbabaya salam, a monumental poem, was performed for the first time. I tried to express from the bottom of my heart everything that I felt and I hope that this was heard.

Nobert Yevdayev heard the recording of my cantata and was so inspired that he translated the poem into Russian and made a book in the US, which will be presented at the Mugham Centre in Baku on 30 August.

TM – How has your current artistic year been?

RA – This year I had concerts in New York, in the Birdland Jazz Club, and, by the way, on 21 August I will perform there at an anniversary concert for the famous American cellist Boris Strulyov, where my partners will be the saxophonist Yaacov Mayman and bassist Eddie Khaimovich and the music will include Fantaziya by the Azerbaijani jazzman Vagif Mustafazadeh.

We – and by that I mean the Azerbaijani Fraternity artistic organisation – held an evening in memory of Vagif Mustafazadeh, which was also bright and eventful. We performed in an artistic union: beginning as a trio, including Edward Perez (a double bassist who has played a lot of afro-Cuban music), Ronen Itzik (drums), the Japanese Keita Ogawa, a percussionist from Nagasaki), at the end we were joined by musicians from the famous ensemble New York Gipsy Allstars: Ismail Lumanovski, a phenomenal clarinetist and ethno-musician from Macedonia, graduate of the Juilliard School who has played a lot in the Balkans and Turkey, and also Tamer Pinarbashi – a phenomenal musician playing the kanun like a guitar, without plucking. Ismael Fernandez, from Madrid but based in New York, was playing flamenco with us. We also played improvisations on melodies by Mustafazadeh such as March and his improvisation of Alekper Tagiyev’s melody Bakı gecələri (Baku Nights), as well as some of my compositions, including Balkan Blues.

Later in Qabala (at the Qabala International Music Festival) one of my pieces was played – Yearning for Peace, for the piano and cello, performed by Dmitriy Yablonskiy and Murad Adigezalzade.

TM – Do you remember your teachers? Tell me about them.

RA – In terms of an academic, classical education, I firstly want to mention Olga Khomenchuk because she gave me the initial foundation for an even and correct articulation of sound. This was in secondary music school. Before this there was the education at home through my uncle’s lessons. We listened to mughams a lot and even wrote down transcriptions for them. But in terms of academic performance, working on sound, this was done in Professor Elmira Safarova’s class. Her titanic level and her school undoubtedly reflected on my development as a performer. Although she was stricter as a teacher, she was a very kind person.

TM – Which composer were you brought up to admire in Elmira Safarova’s class? After all isn’t every student pianist a fan of a particular composer? No doubt you felt closest to romanticism, is that right? And how did your teacher react to your passion for jazz?

RA – I loved Bach, Liszt, Rachmaninoff. Nowadays, as a composer, I for some reason gravitate more towards Beethoven. I’m amazed by how much his music was ahead of his time, his era, how brave and progressive it was, and stunning and perfect in its composition. I also loved the music of Ravel, Bartok, Stravinskiy and many others.

Regarding my passion for jazz, Elmira khanim liked this. And even when I was studying in the second year of the conservatoire (this was in 1996) we put on a double concert, in which the first part was a classical performance and in the second I played jazz in a trio – together with Parviz Mamedov (double bass) and Iskander Aleskerov. Renowned accordionist Enver Sadigov joined me on stage as well, playing a few of my compositions alongside me. I know Enver since we used to collaborate with the famous Azerbaijani vocalist Briliant Dadasheva. As I remember now, it was in winter, it was cold, and there was a full house. Elmira khanim’s favourite jazz melody was Autumn Leaves by Vladimir Kosma, which I also improvised to at the concert.

I’m also grateful to my teachers at the New School University, the composer David Del Tredici and David Loeb, and all the jazz masters who taught me their adored profession – Bruce Barth and Ron Carter. They all noticed my gravitation towards Azerbaijani music, mugham, they approved that I drew inspiration and creative impulse from musical sources very close to me.

TM – Would you agree with me that, purely hypothetically, jazz and jazz masters could be separated into two groups – rationalists, who compose from the mind, and emotional musicians, who compose from the heart. I see this clearly and choose the heart – a heartfelt, emotional beginning. For the benefit of budding musicians, which masters do you feel stand out as worth learning from in this regard?

RA – There are of course many of them but I will name Bill Evans, Chick Corea – these are musicians for whom everything comes from the heart. You know, I would also add to what you said: ‘music from the muscles,’ this is when musicians play with their muscles. It goes without saying that there are different paths and directions in terms of how to play; each path is valued individually and none of them are excluded, the main thing is that it’s done sincerely.

TM – Could you add Keith Jarrett to the list of intelligent jazzmen?

RA – For me as it happens it’s the other way around, Jarrett’s music is emotional. He is a class act. In terms of his own music he could be considered very intelligent, but in his interpretation of jazz standards I think that he is actually very humane and soulful. He has a remarkable range of expression both in terms of how he plays and in the tones he chooses as a composer.

I recently went to a concert at Carnegie Hall and, you know, all he played there were improvisations, without standard jazz melodies, the whole evening was built around his own improvisational music. It was genius of course but I also wanted to hear a few of his improvisations on classical standards. There, you could say that he was very intelligent. Before his latest improvisation, he said that he had changed his style, that he was playing differently and trying to avoid harmony and instead trying to build his improvisations without harmony. And the whole evening he tried to play in this way.

Also, in terms of piano skills I again like to mention Keith Jarrett. For me his sound, intonation, this piano mastery he has is unrivalled in my opinion. I also gravitate towards this.

My question about Ruslan’s playing style, about its emotional or intellectual quality was with good reason, immediately you notice the genuine purity of his sound, its wholeness and the well-formed notes. You listen to Balkan Blues and immediately notice the classical alignment in the structure, the blues harmony lightly combining with Balkans folk intonations and its flexible, dance-like rhythm. And in his version of Vagif Mustafazadeh’s Fantaziya, Ruslan in every way tries to communicate his expression, to generalize Vagif’s folk patterns, at times softly melting away, at times engaging his voice (including his vocals in a mugham style), at times communicating its power in a massive, swing ensemble. His surprisingly songlike sound is remarkable, clearly revealing his spirit as a folk lover or folklorist, with a special feel for folk expression. Regarding this, Ruslan says the following:

RA – My former teacher Elmira Safarova said:

‘‘You should hear yourself; your voice should resonate and return to you. If you can hear your sound yourself, then others will also hear it. The sound should leave and then return to you. You should contemplate it, feel it and not just hurl it at the chords or the piano.’’

And so for me, especially lately, even when I do some complex improvisations, this smooth, almost Chopin-esque style and technique – although it doesn’t always come off! – remains one of my main goals. It’s a part of the music, a part of the composition.

TM – What for you makes successful jazz music or a successful jazz project?

RA – My personal opinion is as follows: successful music means that without doubt it came from the heart. If the art is sincere then you feel this and all the same sooner or later it will be successful. Even if nobody perceives this straightaway, nevertheless it will be successful. Music, like any type of art, must be heartfelt.

It was in this sort of sincere, warm environment the musician loves that his first concert since returning, called Barrel Jazz Nights, took place in the seaside music theatre, gathering his friends and relatives and the Baku jazz elite, and featuring his partners – Edward Perez (double bass), Ronen Itzik (drums), Kamran Kerimov (nagara), Shahriyar Imanov (tar), Elnur Mikayilov (kemancha), Ismael ‘‘el bola’’ (flamenco vocalist), Alafsar Ragimov (balaban). The evening shone with Ruslan’s dedications to Vagif Mustafazadeh, as well as his own pieces and flamenco-jazz improvisations, inspired by the flamenco style and cante jondo singing.

Naturally, we hope for many new concerts and projects by Ruslan Agababayev, who is worthily promoting his beautiful homeland, the land of Azerbaijan.

About the author: Turan Mammadaliyeva is a jazz and mugham expert and frequent contributor for Visions.