Once known as the Jazz capital of the Soviet Union, the musical genre is still very much alive and well in Baku and Azerbaijan, writes Neil Watson. The following article was produced in collaboration with Couleurs Jazz magazine.

Azerbaijani jazz has a long history that dates back 90 years, almost to the earliest days of recorded jazz. The first band in the country was the Eastern Jazz Band, which featured vocals by the tenor Huseyngulu Sarabski (great-grandfather of Isfar Sarabski, a leading contemporary jazz pianist) who toured the Soviet Union. In 1927, Coretti Arle-Titz – a vocalist of Afro-Mexican origin – gave her first concert in Baku to wide acclaim.

In Soviet times, attitudes towards jazz across the USSR varied according to the prevailing political climate. Obviously, the music had evolved in the US, but it was a product of the underprivileged and oppressed in the American ‘melting pot.’ However, it was sometimes difficult for jazz musicians to perform openly.

Despite this, in the 1930s, such Azerbaijani composers and musicians as Niyazi and Tofiq Quliyev played a role in the development of Azerbaijani jazz. Having been recognised for his talent by Alexander Tsfasman, Artistic Director, All-Union Jazz Orchestra, Tofiq Quliyev became the pianist in this influential big band. Collaborating with orchestral conductor, arranger and composer Niyazi, he founded the first Baku Jazz Orchestra. This achieved state approval and even went to the front line during the Great Patriotic War, where it became the orchestra of the 402nd Transcaucasian Infantry Division, boosting morale at this bleak time of uncertainty.

Following the war, composer Rauf Hajiyev established a jazz orchestra under the auspices of the Magomayev Azerbaijan State Philharmonic Society, achieving the diploma of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of Azerbaijan in 1964, with Hajiyev being appointed as Azerbaijan SSR Minister of Culture a year later. Simultaneously, saxophonist and clarinettist Tofig Ahmadov launched several small groups before establishing the Azerbaijani Popular Music Radio and Television Orchestra. Although attitudes to jazz had changed since the death of Stalin in 1953, its American origins led to it attracting varying degrees of state support and condemnation and hence Hajiyev decided to use Azerbaijani mugham and folk music as the basis for many of his arrangements, thereby paving the way for further developments in the late 1950s and 60s.

Jazz musicians were often regarded as ideologically suspicious, none more so than Parviz Rustambeyov, a clarinettist and tenorist who passed through the ranks of the Tofiq Quliyev and Eddie Rosner Big Bands. He was described as ‘the Soviet Benny Goodman’ and attracted plaudits from such luminaries as composer Yuri Saulsky, who described him as: a top-class musician and an improviser of purely natural essence. Despite this, he was arrested by the KGB in May 1949 and died in prison under mysterious circumstances a few months later at the age of 27. Thankfully, attitudes to the music were further relaxed when Leonid Brezhnev – a lifelong jazz fan – became the Soviet premiere in 1964.

Musical revolution

The national music of Azerbaijan is mugham, and although its harmonic structure, metre, scales, and instrumentation differ vastly from western music, there are some commonalities with jazz, in that there are specific ensemble passages at the beginning and end of each piece, and between those there is room for improvisation around the chords and melodies. This high level of improvisation and personal interpretation made Baku very receptive to jazz music, and in the 1950s and 60s jazz musicians from across the Soviet and Eastern bloc flocked to Baku, which became known as ‘the Jazz Capital of the Soviet Union.

Influenced by such American groups as The Hi-Los and The Four Freshmen, the Qaya Vocal Quartet comprised Teymur Mirzayev (leader), Arif Hajiyev, Lev Yelisavetsky and Rauf Babayev. They performed their own interpretations of the American standard song repertoire alongside versions of Azerbaijani folk songs, and thereby founded the tradition of Azerbaijani jazz vocals.

The development of postbop modal jazz in the US in the 1950s and 60s by such luminaries as Miles Davis, Bill Evans and Ahmad Jamal paved the way for a very Azerbaijani musical revolution.

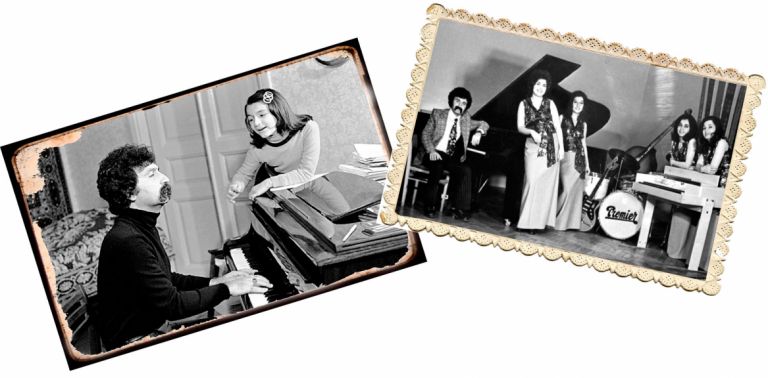

Taking Azerbaijani mugham as a point of departure, classically trained pianists and composers such as Rafiq Babayev and Vagif Mustafazdeh synthesised this with modal jazz to create a form of ethnojazz known as jazz-mugham. Often performed in the standard jazz trio format of piano, bass and drums, the work of Vagif Mustafazadeh attracted particular plaudits, not least for his richly ornamented approach to the piano. Often said to be ‘the Father of Azerbaijani Jazz,’ trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie said he had created “the music of the future” and blues guitarist BB King commented:

People call me the King of the Blues, but if I could play the piano like you do, I would call myself God.

Contemporary artists

Despite suddenly passing away at the age of 39, the influence of Vagif Mustafazadeh cannot be underestimated. Almost all jazz musicians in Azerbaijan today owe much to his legacy – the youthful Isfar Sarabski, who won the Solo Jazz Piano Prize at the 2009 Montreux Jazz Festival – regularly performs his March in his sets; Emil Afrasiyab has undertaken his own transcription of Vagif’s Piano Concerto and frequently plays his compositions Aziza and March; and his daughter Aziza Mustafazadeh has taken the jazz-mugham concept even further, adopting a mystical approach in her own compositions, often ornamented by her own khanande-influenced scat singing.

The breathtaking Shahin Novrasli often collaborates with his brothers on the national instruments of tar and kamancha to produce an effortlessly accessible synthesis of jazz, mugham and the West and East. Another pianist, Amina Figarova, comes from rather a different background, that of freeform jazz, having made her career in the Netherlands and the US. Latterly, Elchin Shirinov – a musician from a folkloric background – has been improvising in and around folk and Azerbaijani classical themes, whilst his compositions still incorporate the microtones and eastern harmonies of mugham. His pianistic pyrotechnics are frequently applied to such folksongs as Gul Achdi, and he has found a joyous groove around the famous Waltz theme from the Seven Beauties ballet by Qara Qarayev. He has also reworked an aria from the 1910 operetta O Olmasin Bu Olsun (If not that one, this one) by Uzeyir Hajibeyli – the father of Azerbaijani and Eastern classical music – into non-metrical form, enabling spirited interplay with the drummer.

Naturally, contemporary jazz musicians are well versed in international developments in music and are collaborating with their counterparts from across Europe and the US. Isfar Sarabski, despite being immersed in the traditions of his country’s mugham, folk and jazz music, is also a funk aficionado, as made evident in his own compositions, such as G-Man which he frequently performs alongside his inspired arrangement of themes from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake ballet, the blues-influenced Insurance Salesman, and Astor Piazzolla’s romantic Oblivion.

A similarly exciting approach is adopted by Emil Afrasiyab, whose composition Two Worlds develops from a rhapsodic solo introduction to reach a breathtaking tempo, incorporating eastern harmonies and demonstrating his devastating dexterity. He even performs free-jazz variations on the 6/8 traditional Azerbaijani dance Shahlakho.

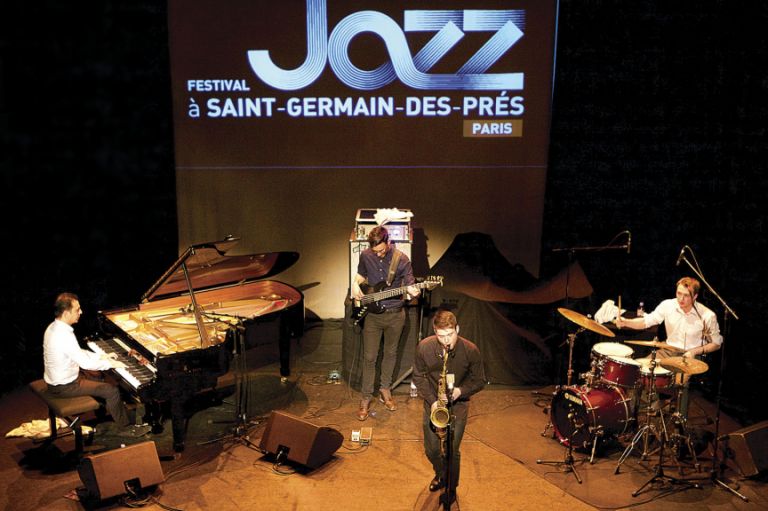

Baku hosted its first jazz festival in 1969, and now the annual Baku International Jazz Festival, organised by saxophonist Rain Sultanov, attracts some of the world’s greatest talents, including Billy Cobham, the late Joe Zawinul, Charles Lloyd and Stanley Clarke, alongside the brightest talents from Azerbaijan and the post-Soviet world. Naturally, such collaborations have had an impact on Azerbaijani jazz, and the work of Isfar Sarasbki and Elchin Shirinov, for example, is replete with funky repeated figures, whereas Salman Gambarov’s work firmly falls into the category of jazz-rock fusion. Tenor saxophonist Rain Sultanov takes a different approach, combining the fusion of Michael Brecker with classical, mugham and world music instrumentation and harmonies.

With high-calibre musicians aplenty, jazz is very much alive, well and prospering in Azerbaijan.

About the author: Neil Watson is the chief editor of TEAS Magazine.