After a brief hiatus Visions continues its series of interviews with talented young Azerbaijanis living around the world. This time we speak to Tural Aliyev, a PhD researcher at the University of Geneva hoping to apply his passion for making cities economically competitive and ecologically sustainable to his hometown, Baku.

VoA: What brought you to Geneva?

I studied my bachelor’s degree in Azerbaijan, then I moved to France for my graduate studies and lived there for six years. During my studies in Azerbaijan I developed a special interest in the architecture and urban planning of French-speaking countries. Having large French-style buildings in central Baku and Baku’s nickname as ‘the Paris of the Caucasus’ sparked my interest. I was captivated especially by the mysterious medieval antiquity of French cities, French Baroque architecture and Haussmann’s 19th century architecture in Paris.

My education in Azerbaijan gave me a solid foundation in understanding architecture but in my studies in France I learned to deeply analyse the challenges faced by a city. Azerbaijan and other post-Soviet countries didn’t have a professional school for urbanism, architects don’t learn how to properly read a city, and to develop a visual sense of the territory. I wanted to be one of the leading specialists in this field and apply that knowledge to my country. In France I discovered my interest in urbanism and in particular in creating ‘place identity’ in cities. I wanted to have a significant role in transforming Baku from an industrial city to a smart-sustainable one.

Geneva has become a fantastic example for promoting sustainability, and it projects itself as a sustainable city. At the University of Geneva (UNIGE), there are great research centres that have a strong focus on environmental issues in relation to urban development in different parts of the world. Being supported by the Swiss Federal Government has been another great motivation for my research in sustainable urbanism at the UNIGE’s Institute of Environment Sciences. At UNIGE I also benefit from the university’s collaborations with other world-renowned universities and international organisations, such as the United Nations (UN) office in Geneva.

Could you explain what urban sustainability is and why this subject is so interesting for you?

Sustainability is the capacity to endure - it is how biological systems remain diverse and productive indefinitely. Sustainable urbanism specifically looks to develop cities based on ecological principles. Urban planners and developers are nowadays faced with major global challenges. Climate change and migration are some of the changes that will impact both the millions of people that currently live in and those who will move to cities; according to the UN the population of worldwide city dwellers will rise from over 50% to 70% by 2050. Cities have a large number of people in them living closely. They all need housing, food, energy, clean water, and to dispose of their waste.

The aim of a sustainable city is to create the smallest possible ecological footprint and to produce the lowest quantity of pollution possible, to efficiently use land, compost, used materials, to recycle or convert waste to energy, and to make the city’s overall contribution to climate change minimal. Great examples of sustainable urbanism are the Hammarby Lake City project in Stockholm, which aims to transform an industrial area into an ecological one, and the city of Curitaba in Brazil with its use of buses and green space.

"I wanted to have a significant role in transforming Baku from an industrial city to a smart sustainable one"

I am interested in this topic, because nowadays it is a challenge to find a balance between urban development and the protection of ecosystems. The first step is to think how to invest in sustainable urban development. “Green” products and services may cost more initially but in the long run they will often save or generate capital, which in turn should create great appeal for investors, governments, and more importantly become beneficial for citizens and their city. I believe Baku needs to be transformed from an industrial city to a sustainable one. Baku wants to be a global city, and to do so it has to have a model of sustainable development so it may become an example on an international level.

Development requires taking into account people and the natural environment, and I find that the sustainable approach to urban development also benefits the human ecology. Part of the thinking in human ecology is on how to manage Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) and refugees, which is particularly relevant to Azerbaijan. As a result of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, 20% of Azerbaijan’s internationally recognised territory has been occupied. About one million people displaced (13% of the population) and 16% of existing housing destroyed. Recently, I participated in a session at the UN Office of Geneva on issues relating to IDPs where Chaloka Beyani, UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of IDP’s, said:

I haven’t seen any other country that has allocated an unprecedented budget ($5bn) and built 89 urban settlements with all the necessary conditions for Internally Displaced Persons as a result of conflict.

Baku has been developing rapidly over the last few years, what are your thoughts on how the city is changing?

Today, we can see new postmodern buildings, new city districts, large renovations and retrofitting projects throughout the city. We can understand these changes as resulting from two historical and different modes of urban development. From 1991 to 2005 the development of the city was chaotic, public and green spaces disappeared, and a rising need for housing resulted in rapid construction of buildings. From 2005 to 2016 the development of the city was much more controlled, there was restoration of public and green spaces, the renovation of the city centre, retrofitting of the industrial Black City area, the implementation of more effective public transport systems and the appearance of skyscrapers to create a positive (modern) image of the city.

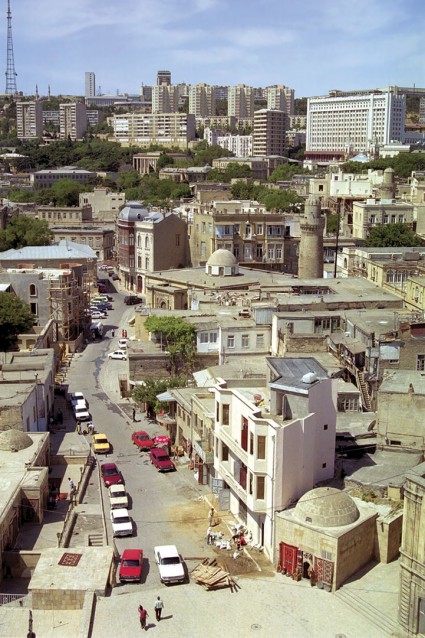

An aerial view of the the Black City suburb (above), so called due to the black soot and smoke emanating from the quarter’s oil factories and refi neries at the end of the 19th century, beginning of the 20th century. The area is currently being developed as part of the White City project (plan below), which will be home to contemporary residential, business and entertainment complexes as well as parks and green space

An aerial view of the the Black City suburb (above), so called due to the black soot and smoke emanating from the quarter’s oil factories and refi neries at the end of the 19th century, beginning of the 20th century. The area is currently being developed as part of the White City project (plan below), which will be home to contemporary residential, business and entertainment complexes as well as parks and green space

Today, the image presented by Baku is of a megacity with great urban potential, with signature modern and innovative architecture, a city that wants to be a global city, organising international events and acting as a centre for sports competitions. Obviously this all goes towards creating a positive image, attracts investment and tourism and is a good way to promote our capital’s potential to the world. But if Baku wants to be a global and sustainable city, it’s important to integrate its natural capital.

green products may cost more initially, but in the long run they will often save or generate money. There is a benefi t for investors, for the government and more importantly for citizens

Firstly, a global city is not only determined by its density, iconic architecture or organisation of international events, it’s also about integrating opportunities created through its natural environment and showing its capacity to reduce environmental damage and provide for the wellbeing of the population. Baku wants to attract tourism and investment. But shouldn’t this economic competition also be driven by the quality of life, the experience of living and working in and visiting cities rather than by those superficial aspects such as having the tallest building or the most spectacular monuments?

Secondly, as I mentioned, I think that the chaotic development of Baku has stopped in the most recent years and if we want to provide comfortable living conditions for the people, we must develop a green development strategy encompassing parks, squares, and improving the environment - which is an important global issue. Projects in this direction include the urban retrofitting of the Black City and the environmental retrofitting of Lake Boyukshor, which are being implemented separately and which in my opinion lack a concept, a plan that links them effectively. We can see this kind of separate development in other parts of the city too.

Thirdly, education is obviously very important. The lifestyle of Baku has a negative impact on the environment. For example, owning big polluting cars versus alternative and ecologically friendly transport, the desire to construct modern skyscrapers that unfortunately distribute heat into the city, and the destruction of green spaces in order to build commercial buildings - these are not examples of thinking sustainably. It is important to promote sustainability through the media and to encourage people to think differently.

We also have to think not just about preserving natural ecosystems but also about creating new ones. Many cities are paying a lot of attention to this. For example, the Los Angeles River (USA) revitalisation project or Seoul’s Cheonggyecheon (South Korea) river urban renewal project. Retrofitting has become one of the greatest trends in urbanism today. Baku has good potential to be more walkable, with more public spaces, a deep social mix and good quality of life. This originates from the city’s first master plan implemented by German civil engineer Nikolaus Von der Nonne, which accommodated the Old City, Seaside Boulevard and promenade area around Fountain Square. Today we can build on this approach.

How do you hope to apply the concept of urban sustainability to Baku?

My doctoral research is on incorporating individual retrofitting projects into a coherent programme aimed at restoring the natural values of the Absheron peninsula and finding new approaches to creating comfortable living conditions in our capital, taking into account environmental factors. In other words, my task is to develop a common regional and green approach to these various projects.

Our entire approach is based on the well-being of the population and today’s trends in urbanism – democratic growth, the importance of the human and natural ecology, the role of IT technologies, overconsumption, urban sprawl and densification issues. The main concept for tomorrow is that in every part of the city, inside and out, people should have clean air to breathe and access to clean drinking water. At the end of our research, I plan to show a master plan to stakeholders about the future development of Baku.

Baku needs to be transformed and I am sure this research will be of value in terms of making our capital a sustainable city.

How do you feel the city can develop in an ecologically friendly way?

Of course, the environment is the foundation of our development but this cannot be separated from other issues. It’s crucial to have a master (structural) plan at the national and regional level, which should involve all the stakeholders - private sector, NGOs and the citizens - and connect various fields (environment, urban planning, economy etc.). Secondly, we have to think about how to disperse Baku: 36% of the country’s population lives on 6% of the territory. The Baku region provides 85% of GDP, which, needless to say, is huge.

This imbalance shows the importance of the Baku region but we mustn’t forget that Azerbaijan is divided into 10 economic regions, 66 administrative districts, and eight cities of national importance. This is one of the reasons why we need to have strategic planning at different levels. Compare this situation to a European country such as France where the capital is a major political, economic, and demographic centre. The Paris region generates more than 30% of French GDP, or 600 billion euros, but accounts for less than 19% of the metropolitan population (2016). The London region generates about 22% of the country’s GDP and about 13% of the population nationwide. The region of Madrid generates about 13-14% of the GDP but accounts for about 14% of the population nationwide.

The ecological standard of city construction is also important. Countries in the “Western” world have their green standard for buildings such as LEED (USA), BREEAM (UK), ESTIDAMA (UAE), Green Star (Australia). This includes a set of rating systems for the design, construction, operation, and maintenance of green buildings, homes, and neighbourhoods which helps property owners and users to be environmentally responsible and use resources efficiently. Materials used in construction should correspond to relevant ecological standards. Baku should also think about a climate plan and sustainability reports for public and private companies.

Lastly, there is the importance of education - from primary to high school and university level. In recent years, the non-governmental sector has its own initiatives to protect the environment. Besides state programmes, the Heydar Aliyev Foundation has environmental projects such as ‘everyone plants a tree.’ Another non-governmental organisation, IDEA (International Dialogue for Environmental Action), has driven environmental initiatives locally and internationally. These sorts of initiative promote ecological thought in Azerbaijan and urge the population to protect the environment.

You recently took part in the 4th World Congress of Azerbaijanis in Baku. What was the purpose of the event and why did you think it was important to attend?

Azerbaijan is a young and dynamic country, which restored its independence only 25 years ago and was less well known than its neighbours. Today, the country has a positive image and a big reputation internationally. Europeans’ views about Azerbaijan are becoming more positive. We also have a significant number of Azerbaijanis living abroad who make up our diaspora network. Today we need to harness the intellectual wealth and investment potential of all Azerbaijanis around the world for the country’s development.

Over 500 representatives of Azerbaijani Diaspora organisations from 49 countries, 50 influential foreign politicians, public figures and scientists attended this congress. The Azerbaijani state invited all Azerbaijanis living abroad to invest in their homeland – financially, intellectually and by visiting at least once a year, which can help to develop the tourism sector.

We had the opportunity to discuss important goals to achieve before the next congress, to exchange views on bringing the truth about Azerbaijan to the international community, attracting young people to the diaspora movement, establishing lobbies etc. I argued the importance of investing in the science and academic fields via the Azerbaijani media, because these areas can influence a broad range of people - students, professors, experts who want to know the truth about Azerbaijan. It’s also very important to invest in Azerbaijani students - some of them face financial difficulties abroad.

Is there an active Azerbaijani diaspora in Switzerland?

France and Switzerland are popular countries in which to study among young Azerbaijanis. When I moved to Switzerland, I was positively surprised about the high level of collaboration between Swiss and Azerbaijani governments. We work relatively closely with the Azerbaijani permanent mission in Geneva as well as with other international organisations linked to the University of Geneva to develop partnerships.

Nowadays, various countries pay attention to international governance and contributing actively to international organisations. I would like Azerbaijan to give greater support to Azerbaijanis wishing to integrate into international organisations. For example, internship programmes at UN organisations or Junior Professional Programme are unpaid but developed countries offer schemes to support their citizens. If Azerbaijan were to support this kind of programme, then it would be easier to integrate into the UN.

Or this support could be in the urbanism and architecture field. For example, we work closely with experts from the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). They have a project called “United Smart Cities” which aims to address the major urban issues in medium-sized cities of countries with economies in transition in the UNECE region. Teams of local and international experts are working together and advising on measures to improve each city’s sustainable development. Belarus (Polotsk), Kazakshtan (Aktau), Ukraine (Vinnytsia) and Armenia (Goris) already have their smart city profiles. Why hasn’t Azerbaijan got a medium city profile? The ancient and charming city of Qabala or another Azerbaijani city could be part of this programme.