Recent escalations in tension between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the occupied Nagorno-Karabakh region came to the forefront of international media attention at the beginning of April, when the bloodiest military clashes since the 1994 ceasefire showed that the conflict is far from frozen.

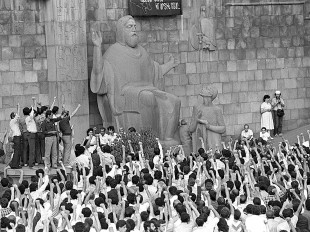

In the late 1980s, the nationalistic fervour that gripped various parts of the USSR transformed into hotbeds of ethnic conflict. Following the USSR’s dissolution, several breakaway regions emerged in the former Soviet republics. From the very beginning of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict both parties, Armenia and Azerbaijan, have had very different interpretations of the conflict and both have accused the other of igniting it. But unlike the other separatist regions in the former Soviet space, Nagorno-Karabakh initially claimed unification with Armenia rather than independence. Armenia not only backed the separatists’ claims but also supplied belligerent Armenian groups with arms and finance. Armenia not only claimed Nagorno Karabakh for itself but also launched a military invasion of Azerbaijani territories. Following the dissolution of the USSR, in order to distract global attention from the aggression of one state against another, Armenian policy towards Nagorno-Karabakh switched from annexation to the right to self-determination and demanding Nagorno-Karabakh’s independence.

In the early years of independence, Armenia skilfully benefited from the power vacuum in Azerbaijan to occupy seven other Azerbaijani regions surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh. In response to this occupation and the accompanying ethnic cleansing, the UN Security Council passed four resolutions supporting the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan and demanding the withdrawal of Armenian forces from the occupied territories. In 1994, with the help of Russian mediation, the parties signed a ceasefire agreement and agreed to pursue a political settlement of the conflict. The OSCE Minsk Group co-chaired by France, Russia and the United States was assigned to find a peaceful resolution.

During the past 22 years since the ceasefire agreement, Azerbaijan has remained committed to a political settlement of the conflict and has tried to resolve it by peaceful means. Despite fruitless peace negotiations, it has managed to strengthen its stance with resolutions adopted by the UN General Assembly, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) and the European Parliament, which have recognised the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan and urged Armenia to withdraw from occupied lands.

On the other hand Armenia’s stance towards the conflict’s resolution is to maintain the status quo and buy itself time by prolonging the occupation. The reports of the OSCE fact-finding missions in 2005 and 2010 supported the Azerbaijani claims that Armenia was conducting illegal settlement in the occupied territories. Indeed Armenian policy makers themselves have openly admitted that since the beginning of the Syrian crisis, hundreds of Syrian-Armenian families have been illegally settled in the occupied territories. Azerbaijan has repeatedly conveyed its concerns over these illegal settlements and stressed that Armenia’s actions are aimed at artificially changing the ethnic map of the occupied territories.

Peace process & Madrid Principles

Since the 1994 ceasefire agreement no progress has been made towards a peaceful resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. The OSCE Lisbon Summit in 1996, the two-phase peace proposal of the OSCE Minsk Group co-chairs in 1997, the OSCE Istanbul Summit in 1999, the Paris and Key-West Peace Talks in 2001 and the numerous bilateral meetings between the Armenian and Azerbaijani presidents during CIS Summits have not led to any tangible results.

The UN Security Council passed four resolutions supporting the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan and demanding the withdrawal of Armenian forces from the occupied territories

In 2007 at the OSCE ministerial conference in Madrid, the OSCE Minsk Group proposed a peaceful settlement to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict to the Armenian and Azerbaijani foreign ministers. This was a continuation of the Prague Process and embraced both the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan and the right to self-determination of the people of Nagorno-Karabakh. During the G8 summit in 2009, the presidents of the countries co-chairing the Minsk Group (France, Russia and the United States) released a joint statement calling on both parties to finalise an agreement according to the following basic principles established in Madrid:

Despite the parties agreeing to the framework of the Madrid Principles, Armenia later pulled out and refrained from detailed comments. Some political analysts commented that Armenia had been dissatisfied with the call for a phased withdrawal of all Armenian troops from the seven other occupied regions of Azerbaijan before determining the status of Nagorno-Karabakh, and that to avoid public dissatisfaction the Armenian authorities had stepped back from the Madrid Principles.

Since the 1994 ceasefi re agreement no progress has been made towards a peaceful resolution

The persistent deadlock of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has prompted the Azerbaijani side to explore alternatives to the Minsk Group. A draft resolution entitled Escalation of violence in Nagorno-Karabakh and other occupied territories of Azerbaijan by British MP Robert Walter failed to attract enough votes in PACE after the following statement of protest by the OSCE Minsk Group co-chairs:

We understand that the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) may consider resolutions on the conflict in the near future and remind PACE, and other regional and international organizations, that the Minsk Group remains the only accepted format for negotiations. We appreciate the interest paid by PACE members, but urge that steps not be taken which could undermine the Minsk Group’s mandate from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe or complicate ongoing negotiations.

Armenia’s reluctance to engage in the peaceful resolution of the conflict and the inertia of international organisations, have increasingly pushed official Baku to regard force as the only solution to the conflict.

The Four-Day War

The bloodiest clashes between Armenia and Azerbaijan on the contact line of Nagorno-Karabakh since the 1994 ceasefire began on 2 April during the visits of Armenian and Azerbaijani presidents to the Nuclear Security Summit in Washington D.C. Both states accused each other of violating the ceasefire first and dozens of military servicemen as well as some civilians on either side were killed. On 5 April, Moscow-brokered peace talks resulted in a mutually agreed truce.

The persistent deadlock of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has prompted the Azerbaijani side to explore alternatives to the Minsk group

As a result of the short military clashes, the Azerbaijani army took control of some strategically important heights which will offer greater protection to civilians on the Azerbaijani side. In a recent interview with the Yerevan-based Radio Impuls 106.5 FM, Armenia’s former Deputy Defence Minister Arkady Ter-Tadevosyan, who led an offensive on the Azerbaijani town of Shusha in 1992, admitted that the Azerbaijani army had fulfilled its objective within a short space of time.

The Azerbaijani army’s response to the ceasefire violation during the Four-Day War was harsh without amounting to a full-scale offensive, but aimed to bring Armenia back to constructive dialogue. After all, during a meeting of the Security Council, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev noted that, Azerbaijan will not take part in negotiations for the sake of negotiations, according to Interfax.

The president’s strong posture is based on Azerbaijan’s military superiority over Armenia. During the last decade Azerbaijan has increased its military spending by over tenfold. The four days of clashes also served to destroy the stereoptype, both inside and outside the country, of the Azerbaijani military as a defeated army. And last but not least, the recent escalation of tension on the Nagorno-Karabakh contact line between Armenia and Azerbaijan drew the attention of big powers back to the conflict. The extraordinary meeting of the OSCE Minsk Group co-chairs in Vienna on 5 April as well as the recent visits of Sergey Lavrov and Dmitriy Medvedev to the region may give fresh impetus to the stalled negotiation process.

Way out of the current situation

Reestablishing constructive peace talks over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region seems the only right step for the time being. Settling the conflict depends on both sides compromising. Azerbaijan has declared its readiness to compromise by offering Nagorno-Karabakh the highest possible autonomy within Azerbaijani borders, in accordance with the Helsinki Final Act of 1975. The Azerbaijani proposal is the only possible win-win solution for the conflict. By contrast, the maximalist approach of Armenia has deprived it of joining important regional energy and transportation projects and left it a prisoner of the conflict. This has had a devastating impact on the economy of the landlocked country.

After the Second World War, European countries realised that the only way to live in peace and harmony was to promote regional cooperation among European countries and so far this model has succeeded. The countries of the South Caucasus can apply this model as well. Azerbaijan and Georgia have been enjoying strong economic and political relations, if Armenia makes the right political decisions it can turn the South Caucasus into a prosperous region.

About the author: Elmar Mustafayev is studying a PhD in political science at the La Sapienza University of Rome.