In the third installment of her grandfather’s jazz memoirs, Visions’ Camilla Rzayeva focuses on jazz pianist Rovshan Rzayev’s musical adventures with the legendary Azerbaijani singer and People’s Artist of the USSR, Muslim Magomayev. The previous two articles – Memoirs of an Azerbaijani Jazzman (September-October 2015) and On Tour with with Rashid Behbudov (November-December 2015) – can be read online at www.visions.az.

My mother once told me a way to tell if a singer is really good: If his or her voice gives you goosebumps, then that voice is really something. It means it gained power over your senses.

After some serious thinking, I did in fact find a performer whose voice to this day gives me goosebumps every time I hear it. To the opening chords of Melodiya and surrounded by countless photographs, I start this last chapter about my grandfather’s tours. This time with none other than the maestro Muslim Magomayev, a truly magnificent musician.

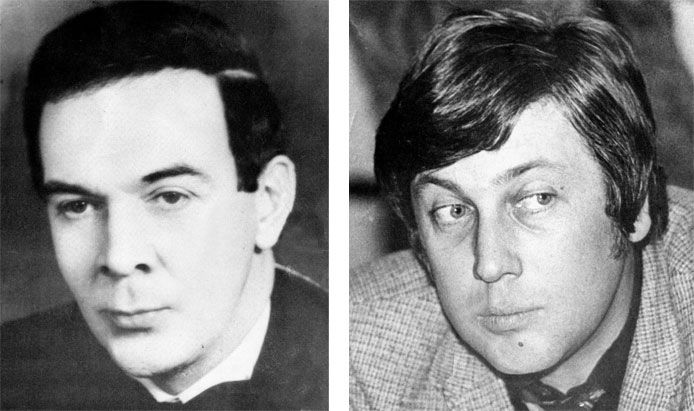

Rovshan, Vagif (Mustafazadeh) and Muslim met when they were still in school (1950s), united by a persistent tendency to have simple boyish fun or “adventures” for them; but also united, unknowingly, by an undeniable talent that was later to bring them back together for their most memorable musical collaborations.

Practice makes perfect, my grandfather says: oftentimes Vagif and I would look for empty classrooms with a grand piano to practise jazz, while Muslim was looking for one to practise his singing.

Such caution was due to the fact that this was an elite school where jazz wasn’t welcome and in some cases one could have been expelled for the mischief of playing it. As for Muslim, he kept his first singing attempts private for a very long time, shying away from outside ears.

We would take turns waiting by the classroom while it was in use to get in as soon as it was free. It was always jazz for me and Vagif and mostly classical for Muslim. That voice though… incredible. And the further we moved, the more he was developing, constantly searching and finding himself. But even then he was very developed all round: as a pianist, as a performer and also as an artist and a sculptor. Very versatile.

Ten days of Azerbaijani Art in Tashkent (1980)

Until 1978, they met rarely, mainly at government events, where Magomayev and Rashid Behbudov were always the honoured performers. The year 1980 saw a celebration of Azerbaijani art in Tashkent, where the two friends finally reunited for the first time since my grandfather had left for army service. This was also when Magomayev invited him to join his orchestra as a pianist.

Muslim and Behbudov were loved not only in Azerbaijan and the Soviet Union, they were loved all over the world

After so many years of working side by side with Rashid muellim, he says, it would have been wrong to simply leave the collective all of a sudden. Especially since they were in the middle of a tour and Behbudov had previously discussed his plans to retire after the last concert. So they collectively, out of habit perhaps, decided that the transition to Magomayev would happen after Behbudov had retired.

They played their last concerts together as a team, Rashid Behbudov received the Hero of Socialist Labour award and soon after stopped all his concert work. Within a couple of months my grandfather was on the road once again, this time to Moscow, heading towards yet another collaboration that brings him many fond memories today.

The Azerbaijan State Variety-Symphonic Orchestra

Muslim’s orchestra was based in Moscow and as soon as I arrived we started rehearsing the programme, followed by our first tour together.

Just like with Behbudov before, the first tours with Magomayev were around the Soviet Union and then they went abroad.

The orchestra was made up of musicians from Moscow and Baku, says Rovshan. This wildly talented mix was called the Azerbaijan State Variety-Symphonic Orchestra and directed by People’s Artist of the USSR Muslim Magomayev.

He worked a lot, but rarely left on tour for more than a week. We always overdid the programme though, since there were three to four concerts per day. In summer – stadiums full of people; in winter – covered hockey fields. Always a sea of people, admirers of his talent.

During one of Rashid Behbudov’s European tours, Magomayev and famous mezzo-soprano soloist of the Bolshoi Theatre and People’s Artist of the USSR, but most importantly Magomayev’s wife, Tamara Sinyavskaya, were also touring in the same city. The joint decision to play a concert together was as spontaneous as their arrival in the same city:

They simply gave us the songs they were going to perform along with the keys in which they sang. And without any rehearsal whatsoever, our ensemble accompanied both Muslim and Tamara. I remember Tamara’s astonishment, asking Muslim later, how is it possible that they played so well without any rehearsal?

Touring with Muslim Magomayev

After the transition Rovshan returned to his original instrument, the grand piano, which he still plays today. Only occasionally, if the situation required, he would switch to double bass or bass guitar when Muslim accompanied himself on the grand. Maybe it’s the similar respect and admiration in his voice but I catch myself drawing parallels between Behbudov and Magomayev. And as I note this, my inner conversation is interrupted by my grandfather:

Muslim and Behbudov were loved not only in Azerbaijan and the Soviet Union, they were loved all over the world. Even when they performed somewhere for the first time where people were absolutely unaware of their existence, they won the hearts of every audience they ever performed for.

This wildly talented mix was called the Azerbaijan State Variety-Symphonic Orchestra and directed by People’s Artist of the USSR Muslim Magomayev

They were incomparable yet similar in their genuine love for their audiences and consequently in how people loved them back. Although different kinds of artist, both had magnificent voices and were internationally acclaimed performers who were always given a standing ovation in every city in which they gave concerts.

As I listen, fascinated, I start to understand something about the music industry and the people involved in it back then. It was a different breed of artists. Today, it seems the requirements for art, whether musical or visual, are somewhat lower. Greater freedom then was like a long-awaited breath of air, whereas now the excess of this same freedom generates an arrogant laziness. Artists in the past seemed to know the true value of success and appreciated each and everyone who came to their concerts.

That voice though… incredible

The evidence for this idea is in almost every story Rovshan tells me. For a big tour across the US, Vladimir Vinokur was invited by Magomayev to be MC. Not a lot of people knew at the time that Vinokur suffered severe back pains that made him lie down a lot between appearances. Enduring the pain, he continued to give his best jokes, never showing a single sign of pain.

We worked in Boston, Washington DC, New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Muslim sang in all the famous concert halls, where the giants of American musical culture were performing. The Americans admired Muslim’s voice and respected the level at which he was performing. Our concerts weren’t politicised, the people that came to listen to us understood that in our case politics had nothing to do with the art we were sharing. And let me tell you one more thing - I’ve worked with a great many musicians and none have ever held the Azerbaijani flag higher than these two (Behdudov and Magomayev – Ed.).

In the years that they worked together, Magomayev rarely cancelled a concert, and even when he did it was due to his respect for the listener. He somehow always knew that the audience could feel when he wasn’t giving one hundred per cent. So even though he could and sometimes did perform sick or “out of voice,” he tried to limit those occasions not to disappoint his valued listeners. Nothing else could stop him from giving the best performance. Not even the weather.

For both Rashid and Muslim – mountains of flowers. Every time I took over the grand piano I couldn’t see past the growing amount of flowers on it

There was this one concert and the venue was an open stadium. Right before the start, we were warned that the weather might worsen and we should consider cancelling. After Muslim’s definitive “no,” with the sound producer we started covering the instruments and all the equipment connected to the power supply. Only the piano was left in the open.

So the concert started and of course pretty soon a little drizzle turned into something very similar to a tropical storm. An umbrella was immediately found and held above Muslim as he was performing. While the rest of the musicians could find a way to move out of the rain, it was kind of problematic for me and my difficult-to-move piano, he says laughing.

It would have been bad enough to just get soaked under the rain, but the water was getting into and under the keyboard and the keys were getting stuck. So I played with one hand, while popping the keys back up with the other. The next song, “Along Piterskaya” (Вдоль по Питерской), was one of those that Muslim liked to play himself. As he sat down and saw what was happening with the keyboard, he asked me what could be done. Since he played wide that gave me enough space to see the problem keys and pop them back up in time for him to strike them again. That concert definitely stayed in our memory for a very long time. Even in the most difficult situations, the show went on.

Winning global respect

Magomayev was highly respected everywhere he travelled. And that kind of respect could only come from true admiration for his talent, since it was not just in Azerbaijan that people knew and admired his composer grandfather, after whom he was named.

People valued his presence in many parts of the world. One of the most memorable places was West Germany. At the time, Germany was divided, and every year, in May they had celebration concerts to mark Liberation Day. Famous artists from all over the world were invited to perform there. I remember it as if it were yesterday, the venue in the shape of an amphitheatre.

None have ever held the Azerbaijani flag higher than these two

Due to the incredible number of famous artists present at all times in the town, security guards were everywhere. The concert would start early, around noon, and would run until evening. Each performer had every minute scheduled: each had a precise time to arrive at the venue, to get on stage. They even performed for a fixed amount of time. Some artists flew in for this one performance and as soon as they were done, they were leaving for the airport. As a sign of deep respect, Muslim was invited to stay for the whole week and only perform one day. During this week, we were treated as very dear guests, taken everywhere, shown everything.

There was always additional security at all the concerts abroad. In the US, security guards backstage were in regular uniforms but the rest were in civilian clothing in front of the stage, not letting people move closer. Nothing could be passed to the artists without a rigorous inspection. But despite all this, the stage was covered in flowers. Always. For both Rashid and Muslim – mountains of flowers. Every time I took over the grand piano I couldn’t see past the growing amount of flowers on it. There were times when not far away from the venue, groups of people would scream out some anti-Soviet slogans. Once in a while someone would try to get inside the venue, but those “bold” attempts were rare and very severely punished.

My grandfather and Magomayev worked together for eight years, from 1980 until 1988, when it became unprofitable to accommodate such an orchestra and, this was when all the military problems were just starting, he says. It was getting very complicated to organise tours. When the Soviet Union collapsed, the orchestra was disbanded.

That was the end of my work with yet another friend, an extraordinary musician, Muslim Magomayev.

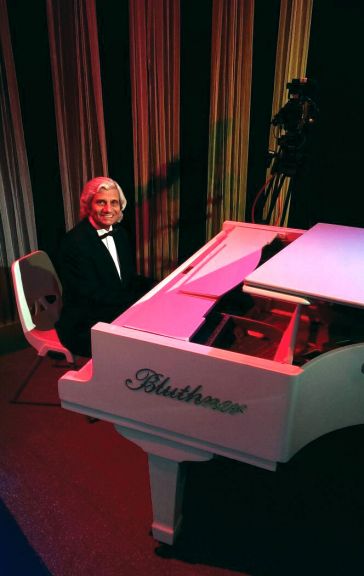

I’m sure there are more stories hidden in the corners of his memory and that there is far more he can tell from the faded photographs in front of him. I can only guess where his thoughts are as he looks away, probably many years from now. Through our in-depth conversations I have been able to live his stories as opposed to just hearing them. But I have also noticed how his current schedule is somewhat reminiscent of how his career initially began.

Fixing his silvery coiffure, there is a certain excitement in the air as he heads out for the evening to play in different venues in Baku a couple of nights a week. And it truly feels like he has found his vocation as I watch him play his Caravan, his facial expression not betraying a single emotion except precise concentration. He prefers walking, admitting that it’s much easier to navigate Baku these days than when he and Vagif Mustafazadeh were headed to their first performances. Walking the same streets as many years ago, he still refers to each by their old names and it seems that despite how time has changed our city, a part of its history still lives within him. And the music goes on…