Pages 86-96

by Dr. Hasan Quliyev & Acad. Teymur Bunyadov

Traditionally Karabakh women were known for their colourful clothing and multi-layered skirts – they would wear eight to 10 skirts at once – while men’s clothes were less varied. The Karabakh diet was seasonal and closely linked to the agricultural year. In their second article for Visions of Azerbaijan magazine, Dr Hasan Quliyev and Academician Teymur Bunyatov look in more detail at the clothing, cuisine, family traditions and festivals of Karabakh in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

by Dr. Hasan Quliyev & Acad. Teymur Bunyadov

Traditionally Karabakh women were known for their colourful clothing and multi-layered skirts – they would wear eight to 10 skirts at once – while men’s clothes were less varied. The Karabakh diet was seasonal and closely linked to the agricultural year. In their second article for Visions of Azerbaijan magazine, Dr Hasan Quliyev and Academician Teymur Bunyatov look in more detail at the clothing, cuisine, family traditions and festivals of Karabakh in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Clothes and fashion

The traditional clothes of Karabakh can be divided into categories: men’s (cloaks, shirts and tunics and undergarments), women’s (under and outer clothing), belts, professional clothing, ceremonial clothing (wedding, mourning, festive), children’s clothes, headgear, shoes and accessories.

Clothes were made from local and imported textiles. The imported textiles came from Russia, Persia, Europe and elsewhere. The choice of textiles increased noticeably in the second half of the 19th century. Red calico, velvet, atlas silk and silk were used, as were cheaper textiles such as chintz (chit), coarse fabric (agh mitqal) and madapollam cotton (humayun aghi). The cheaper fabrics were accessible to all strata of the population. Karabakh women’s clothes were noted for their colourfulness, complexity and variety. Women wore tunic-like blouses, an underskirt (dizlik) and skirt or dress, known as arkhaliq, kurdu and pullu chapkan or zibini.

The arkhaliq (from the word arkha meaning ‘back’) is worth special attention; it was sewn from brocade (zerkhara), velvet, atlas silk, sateen or other textiles of various colours. Unlike the Shirvan arkhaliq the Karabakh arkhaliq had a rectangular cut. The overshirt was simple while the undershirt was similar to a tunic. It was worn over a skirt and fastened by buttons. Karabakh women wore several skirts at the same time, as many as eight or 10. The outer skirt was decorated with braid (silver or golden). In winter one more quilted skirt – yorghan tuman – was worn between the middle and outer skirts; girls did not wear one. One Karabakh winter garment was the kurdu – a sleeveless jacket without a fastener which fitted to the figure. It was worn both indoors and out, but was not worn for work.

The chapkan (zibini) was made from bright coloured fabric and had false sleeves. In Lower Karabakh the pullu chapkan had a different cut from the plain chapkan – it was a sleeveless, thigh-length garment, decorated with Russian imperial coins. Women wore an apron (doshluk) over their clothes, decorated with serme embroidery (small hollow silver tubes), sometimes on both sides.

Women had a range of colourful headgear, including silk shawls (kalaghayi), turbans (chalma), skull caps (arakchin), headscarves (orpak), shawls (shal), veils (charshab, chadra), kerchiefs (lachak) and caps (tasak).

Women’s hairstyles were not so complex. They consisted of two plaits (horuk), with locks (birchak) left over the ears. Girls and women combed their hair smoothly, parting it in the middle. Cosmetics were widely used; special attention was paid to the clearness and beauty of the face. Facial hair was removed and eyebrows were plucked using thread (uz aldirmaq). Special make-up – sume and vesme (mascara) – was used for the eyes and eyelashes. Henna (khina yakhma) was painted onto hands and feet.

Men’s clothes were less varied than women’s clothes. A late 19th-century author wrote about national costume in Jabrail district: ‘Underwear consisted of a straight, short shirt, made of coarse white or often blue fabric, and underpants of the same material that were tightened round the waist by tape; in winter wide woollen trousers were worn and they were also tightened with tape. A padded arkhaliq was worn over the shirt. The arkhaliq is a garment flared around the waist that is always fastened tightly at the middle or to one side. A chukha is worn over the arkhaliq. The chukha is a garment with a short waist and long skirt that reaches below the knee. The head was covered all year round with a short conical cap of sheepskin. Simple footwear (similar to Russian lapti) was made from ox and buffalo hide.’

The most important outer garment for men was the arkhaliq. There were three different kinds of arkhaliq in Karabakh, depending on the cut – single-breasted (onursuz), double-breasted (onurlu – when one breast was worn out or dirty it could be covered by the other side) and ‘single-backed’ (doshu achiq arkhaliq). The arkhaliq was fastened with three buttons. A short sleeveless jacket was worn over the undershirt, jan arkhaliq (qalincha).

Young people wore a leather belt (kemer) over the arkhaliq and chukha; a girdle of different materials (cloth, wool or silk) was worn over the arkhaliq and chukha. Fabric girdles with edging and fringes were also worn and were produced in Russia and Poland. One style of chukha had gathers (buzmeli) while another had rows of bullet holders stitched across the chest (vezneli).

Men wore a variety of hats (papaq). Hats with a cloth top were known as yappa papaq or qara papaq (black cap). Hats came in different colours – qizili papaq (golden cap), gumushlu papaq (silver cap) – and were all round. Other types of headgear were the skullcap (arakhchin), teskulakh and hood (bashliq) and so on.

The most widespread men’s footwear were bast shoes (chariq), woven from plant fibre, but men also wore shoes (bashmaq, mehs) and boots (chakma); women wore mainly patterned shoes (bashmaq), frequently decorated with horseshoes. Woollen socks with a carpet design (gaba jorabi) were very common.

Like most Azerbaijani men, men in Karabakh had moustaches (lopa big, burma big) and beards (long or short). Beards and moustaches were often dyed with henna. Men usually had their heads shaved. A 19th-century source says: ‘Tatars have their heads and sometimes beard shaved, but some Tatars that follow Omar leave tufts on the crown of the head, while the followers of the Ali sect leave locks of hair near the ears.’ A hairstyle for older people was the fringe at the back (dalbirchek). Some young men left a tuft of hair (kekil, tel) on the head. Men’s and women’s hair styles varied according to age. For example, after marriage hair styles for both sexes changed.

Cuisine

Karabakh’s traditional cuisine did not differ from Azerbaijani cuisine as a whole. Food, as well as other elements of material culture, depended directly on the economy of the region and the prosperity of the families. Agriculture and animal-rearing influenced the local diet. Cuisine was, of course, seasonal. The winter diet was more substantial and included meat from domestic cattle slaughtered in the autumn (qovurma). A variety of cheese, butter and dairy products were made in summer for consumption in autumn and winter.

The food can be divided into major groups: grain, dairy, meat, vegetables, special occasion food and children’s food.

Grain was milled at water-mills which existed in almost every village. The quality of bread and other rolls and buns depended on the quality of flour; the finer the flour, the better and more expensive the bread. Wheat and rice flour were also made through hand-mills (kirkira). Bread (chorak) was the main grain product. It was made from wheat flour and occasionally from a mixture of barley or millet. There was a wide variety of grain products for daily use and special occasions. Both leavened and unleavened bread was made.

Bread was baked in a tandir – a clay oven built into the ground – or on a saj – a round, cast-iron disc.

One of the main kinds of bread in Karabakh was lavash. Unlike the other regions of Azerbaijan, where lavash was baked daily or every other day, it was baked here in the tandir to last for a long period (15-30 days). Women helped each other with the baking. Before it was served, dried lavash would be sprinkled with water.

Other grain based foods were noodles (arishta and khinqal), porridge (khashil), semolina buckwheat and other grains (yarma ashi). Rice was very popular. A favourite, traditional dish was pilaff (plov or ash), rice served with a variety of seasonings and sauces. Azerbaijan had more than 40 kinds of pilaff, most of which were served in Karabakh.

Dairy products, both liquid and solid, were used together with grain products. Milk was often used in preparing dishes from flour or meal. Dairy products included milk (sud), butter (yagh), cheese (pendir), yoghurt (qatiq), buttermilk (ayran), cream (qaymaq) and sour cream (khama). Three types of churn were used: ceramic (henre), wooden (arkhiq) and leather (chlkhar). A speciality was dried curd (qurut) which was kept underground. Qurut was made in summer, dried in the sun, pressed, sliced and kept. High-quality qurut was solid and could be soften through soaking. Qurut reserves usually lasted until spring.

Meat was an important part of the diet but not as prevalent as dairy produce. Meat was served both hot and cold (soyutma). Mutton (qoyun ati) was the most common, followed by beef (mal ati) and chicken (toyuq ati). Horse-flesh and camel-flesh were not eaten in Karabakh. High-calorie meals such as piti (stew with chickpeas), kufte-bozbash (meatball in broth), dolma (vineleaves, peppers or other vegetables stuffed with mince), and dushbara (pasta-wrapped mince served in a bouillon) were made from mutton. Meat could be barbecued, grilled, fried or roasted. Kebabs were made from lamb, minced lamb, ribs, liver, chicken and fish and could be cooked over the barbecue, in the tandir oven or on the saj. Meat-based soups and stews were widespread (shorba, dushbara, kufta-bozbash).

Unlike dairy produce, which could last for a long period, only the qovurma was prepared in advance for winter. Internal organs were used in dishes such jiz-biz (made from heart, kidneys, liver, lungs, entrails etc.). According to tradition, a serving of liver would make a man strong while heart would make him brave and so on. Fried and boiled meat were served on special occasions.

Fruit, vegetables, various spices (adviyya) and seasonings (khurush, qara) were widely used in Karabakh. Twenty-five kinds of spices have been recorded in Azerbaijan and most of them were used in Karabakh. It is hard to imagine Near Eastern cuisine without spices. Unlike seasonings, spices were not used in large quantities. They were used to flavour dishes and delay putrefaction and thereby preserve meat for longer. Cardamom (hil) was used in meat dishes. Cinnamon (darchin) was used in chicken dishes and lamb soups and stews. Spices from the ginger family included turmeric (sari kok), which was used as seasoning, colouring and for medicinal purposes. Turmeric was always used in pilaff, and bozbash. Another widespread and relatively inexpensive spice was cloves (mikhak). They have a strong smell and were used mainly in making marinades and pickles. Cloves and cinnamon were also used to make sweets.

Karabakh people also made wide use of saffron (zafaran), dried fruit (lavashana), black pepper (istiot), sumac (sumaq), garlic (sarimsaq), mulberry syrup (doshab), sour pomegranate juice (narsharab) and vinegar (sirka, abqora).

Various cultivated and wild vegetables and herbs were widely used: purple basil (reyhan), coriander (kishnish), mint (nana), wild mint (yarpiz), wild sorrel (evelik), dill (shuyud), onion (soghan), water-cress (vezeri) and others. Fresh and dried fruit were also very common in the diet and jam was made from fruit.

Certain rituals surrounded the serving of food. Usually pilaff was the last dish to be served in a meal. This custom was also followed during ceremonial meals. Hot dishes were served with herbs of different kinds, sumac, pepper, onions, vinegar, cucumber, tomatoes etc. Fruit (apples, pears, watermelon, muskmelon, grapes etc.) were served at the end of a meal. There was no strict division between first and second courses. Hot drinks, such as tea and milk, and cold drinks, such as various sherbets (or syrups), buttermilk, atlama (a soft drink made of water and sour clotted milk), iskanjabi (vinegar, honey and sugar) and dogramach (pomegranate syrup) were served. Azerbaijani drinks both quench thirst and stimulate the appetite.

Family life and marriage

Two forms of family were characteristic for Karabakh: large families or family communities and small families (monogamous). Small families predominated and came in two forms: the simple family (parents and unmarried children) and compound families that included grandparents (usually the father’s parents) and other relatives.

Family life was regulated mainly by sharia (Islamic religious law – Ed.) and traditions or adat. The elders traditionally retained seniority in the family, but in the late 19th – early 20th centuries essential changes based on equality and mutual respect occurred in relations between elders and younger people. Although families were patriarchal, sometimes women retained prestige. Women enjoyed freedom, respect and care as well as a degree of authority and independence. A.A. Alakbarov describes the life of Azerbaijani women in Zangezur: ‘Zangezur Turkic women are quite equal with men. The Zangezur woman behaves quite freely, her attitude towards men is simple and she gets married of her own free will.’

Ethnographic and literary sources testify to the existence of family communities (aila icmasi) in Karabakh which is confirmed by place names and linguistic terminology. Terms referring to the heads of large families have survived (aghsaqqal, aghbirchak, qaqa, qada, lala agha, baba and others). The collapse of large families dates from the late 19th century, as in other regions of Azerbaijan, and this resulted in the launch of a clan system. Members of one clan lived in a separate district (mahalla, mahla) and formed socio-economic, ideological and cultural units. Clans had various names in Karabakh: kin (aqraba), offspring (ovlad), generation (nasil), child of the tribe (tayfa ushagi), division (tire, bezelli, uruqturuq). Many settlements here have names that are clearly related to clan – Veliushaghi (Barda), Tekdam (Kalbajar), Tepemehle (Agdam), Khanlar (Lachin) and others. It is also interesting that the members of a clan used the same original surname (Hasanli, Ali ushaqi) but lived in separate small families.

Marriage in these families was patrilocal (i.e. the man took the bride to his home). Marriage to people of other religions was not permitted; marriage between Azerbaijanis and people from other ethnicities living in Azerbaijan was also rare. Various forms of marriage were practised – levirate, sororate, marriage between cousins, abduction (qoshulub qachma) and betrothal in infancy (beshik kertme). Marriage between cousins was the most widespread form of endogamous marriage (marriage between relatives).

Marriage between cousins took four forms: cross-cousins and direct cousins. Direct cousin marriage was preferred, which can be seen in traditional proverbs such as ‘marriage between the son of a paternal uncle and the daughter of a paternal uncle is consecrated by the angels in heaven’ or ‘It’s a pity to give something good to someone else and a disgrace to give them something bad.’ Every family or clan provided the manpower for agriculture in the natural economy, so they were interested in raising new members of the clan.

Levirate marriage was also based on economic factors and the national way of life. Levirate and sororate marriage were relics of early family-marriage traditions in the 11th-12th centuries amongst the Oghuz Turks. According to levirate marriage, a woman had to marry her brother-in-law (qayin) after her husband´s death, while the elder unmarried brother had the right to marry her. This kind of marriage was not forced and the woman´s consent was required. This type of marriage ensured that the dead husband´s property, which was inherited by the woman, did not pass to another family.

While levirate marriage was for economic reasons, sororate marriage had more of a social character: if his wife died, a husband had the right to marry his sister-in-law (baldiz). This marriage occurred mostly if the dead woman left some children, as their aunt was considered the best person to take care of them.

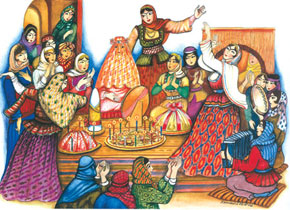

Traditional Karabakh weddings had several stages with many complex rituals. A wedding resembled a theatrical performance with lots of actors – the father of the groom and father of the bride, the friends of the groom and bride, the bride’s ‘auntie’ (who would teach the bride her duties as a wife – Ed.), the toastmaster, the waiters (five or six), cooks (three or four), the organizers of the tea ceremony (chaychi), water-carriers, and so on.

The marriage process (especially rural marriages) went through a number of stages: first was the choice of wife (qiz bayanma, gozalti) and matchmaking (soz kesdi, herisini alma, elchilik, raziliq alma), but before this came another ceremony – preliminary agreement (aghiz bilma); in this ceremony the bride’s parents (especially the mother) were informed about the intent of the opposite side. This meant getting parental consent to the date for the main messengers or matchmakers (elchi) to come, the betrothal (nishan – literally marking), the ceremony of cutting out the bride’s wedding dress (paltar kesdi) and the ceremony of colouring the bride’s hands and feet with henna (khina yakhdi, khina qoyma).

These ceremonies included traditions such as payment for the bride (bashliq), dowry (jehiz), ceremonial marriage (kebin, nigah), presents from the mother to the brothers and sisters of the bride. The groom would be protected by his friends (saqdish, soldish); the bride would be hidden during the wedding ceremonies; the bride would be intercepted as she passed on her way to the wedding (yol kesdi); and there were different local variations of ceremonies to welcome the bride to the groom’s house (uza chikhdi) and of post-wedding traditions.

An important stage in the wedding ritual was the engagement (nishan), known as shirin in some areas, i.e. the bringing of sweets. Khoncha (trays with presents and various oriental sweets), bolts of cloth (depending on the prosperity of the groom’s family), leather shoes, woollen and silk stockings, a sugarloaf (kelleqand) and an engagement ring (nishan uzuyu) were taken from the groom’s home. Wealthy people sometimes invited musicians too.

The wedding consisted of the artistic section (music, dances, and songs) and feasting (qonaqliq) at the bride’s and groom’s homes. Weddings usually continued for three or seven days (in the rich families), with each day of the wedding having a special name and designation.

Karabakh weddings were remarkable for the diversity of the dances, songs and entertainments. A group of three to six musicians (khananda) took part in weddings. There were well-known khananda who were frequently invited. There were men’s and women’s dances and each stage of the wedding had its own dances. Gashangi, tarakama, innabi and jeyrani were all women’s dances, while qazagi-ulduz, bagdadur, asgarnai, mirzei and shalakho were men’s dances.

A compulsory component of a wedding was the dowry (jehiz) which was prepared when a girl was still a child. Some articles of the dowry passed across the generations. Dowries used to be modest and usually consisted of bedding, a bride’s personal things and household articles. Wealthy families ordered more than 100 articles (from thimble cases to curtains for niches) with golden embroidery.

The day before the bride was sent to the groom’s she would be washed and groomed. The most important ceremony was khina yakhdi which literally means ‘anointing with henna’. This was an important ceremony and cause for great celebration amongst the women.

A wedding was a public event and was a celebration for the whole village. Various collective games would be played (shah selim, qara goz, kechal pahlavan, shala oyunu, haji geldi); there would be horse-racing, traditional wrestling and collective dancing (yalli). A.K. Alakbarov writes: ‘Games were usually held during weddings and festivals. Wedding ceremonies followed pre-determined, fixed patterns and had a theatrical character.’ Each ceremonial act was accompanied by music. For example, the arrival at the groom’s house would be accompanied by khosh galdin (welcome), and the bride’s departure from her parents’ house by khosh getdin (be happy).

The bride was taken to the groom’s house on a horse (sometimes in a cart) and she was accompanied by her yenga¬ (the ‘auntie’ who would explain to her her duties as a wife – Ed.), friends and close relatives. A mirror and lamp that had been lit were carried before the wedding party. It was widespread practice for the wedding train to be intercepted (yol kesdi). The bride would be sprinkled with sweets, grain and coins. Metal articles were laid under the bride’s feet and a two or three-year-old boy would be placed on the bride’s knee so that she would give birth to a son.

After a set period (seven days or more) the ceremony of viewing the bride (uza chikhdi) would be held at the groom’s house. Relatives would give various presents to the bride. The wedding ceremony was completed when the young couple visited the bride’s father’s house. This would lift the ‘ban’ on the groom visiting the parents and relatives of the bride. Afterwards the bride would begin her household duties. A bride’s main duty was to give birth, as a childless family used to be criticized by society.

To have many children was a source of pride for an Azerbaijani family. Members of families with many children enjoyed authority and respect among the people. The correct upbringing of children was given special attention. At a certain age the ceremony of circumcision (sunnat) was held. At the age of ten children began to work. Education in work took first place in Karabakh families. The main function of the family was to give children life skills and practical knowledge of how to run a homestead.

Other ceremonies

A great number of traditions, ceremonies and festivals featured in the religious life of the Karabakh population. They can be grouped into pre¬¬-Islamic beliefs, Islamic festivals and ceremonies and national holidays.

Pre-Islamic beliefs proved themselves to be more deeply ingrained in Karabakh life than Islamic ones. The reason for the long maintenance of pre-Islamic traditions can be found in the socio-economic development of the region, the conservation of patriarchal-feudal relations and the specifics of family and domestic life.

A wide variety of pre-Islamic beliefs and traditions were maintained in Karabakh. They included beliefs concerning objects and animals from real life (worshipping of stones, plants, water, fire, animals; worship of metals and the heavenly bodies), images of demons (evil and good spirits), magical ceremonies and so on.

Islamic religious traditions and ceremonies were also frequently part of life, including namaz (prayer) five times a day, pilgrimage to the holy places of Islam (Mecca, Mashad, Karbala), the Ramadan fast and Feast of the Sacrifice (Qurban Bayrami), rituals associated with Muharram, the month of mourning (ashura, qetl gunu, meherremlik), the Prophet’s birthday or movlud. Following all the precepts of Islam was

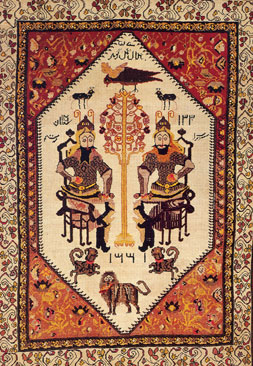

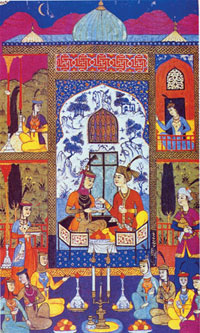

Fragment from a painting on a pencil box. On a Shusha Estate. Mir Mohsun Navvab, lacquer, Shusha, Karabakh, late 19th century

Fragment from a painting on a pencil box. On a Shusha Estate. Mir Mohsun Navvab, lacquer, Shusha, Karabakh, late 19th century The most important dates in the traditional calendar for people who worked on the land were spring field work and preparations for it. The start and successful completion of the spring field work was celebrated since ancient times. A major festival in the spring cycle for the Azerbaijani population of Karabakh was the festival of the first tillage (shum bayrami) that was celebrated on the eve of the Novruz holiday. People prepared very thoroughly for this holiday. The peasants would repair or replace all their agriculture tools. The approach of the holiday mobilized the peasants for the spring field work on which the success of the harvest depended. The celebrations were led by the ‘master of the holiday’, the majqal or ploughman. The main stage of the festival was the first symbolic ploughing; a spot would be chosen nearby for this. The right to plough the first furrow in the field went to one of the professional farmers – jutchu-baba (grandpa-ploughman). Afterwards the ceremonial part of the holiday began – young people sang songs and organized horse races and competitions.

Stock breeders celebrated the herdsman’s or shepherd’s holiday – choban bayrami. The holiday dated back to the move from the winter pasture to the mountains, which was roughly at the beginning of spring. On the first day of the holiday – quzu gunu (Lamb Day) – collective games, magical games and sporting competitions were held.

Another traditional holiday was the flower holiday (gul-chichek bayrami) which was celebrated until recently in spring and early summer. The holiday was accompanied by collective songs and dances, steep cliff faces were climbed, young people competed in national sports such as wrestling (gulesh), the long jump and jumping over bonfires. The girls would give the winners their handiwork (shawls, head-dresses, silk stockings, etc.).

Novruz which was celebrated at the vernal equinox (21-22 March) was of special importance amongst the national holidays. Preparations for the holiday began a month in advance. Celebrations took place on the four Tuesdays preceding the equinox – Water Tuesday (su chershenbesi), Fire Tuesday (od charshanbasi), Wind Tuesday (yel charshanbasi) and Earth Tuesday (torpaq charshanbasi). These Tuesdays were marked by many ceremonies. The Novruz celebrations were very diverse – public performances and varied traditions and ceremonies. The concept of the Novruz holiday was not related only to agriculture rituals. In the foreground was the connection between the spring holiday and the cult of fertility and the revival of nature.

LITERATURE

Narodi Kavkaza (Peoples of the Caucasus), Vol. 2 Moscow, 1962.

Q.A. Quliyev O pakhotnikh, orudiyakh i sistemakh zemledeliya v Azerbaydzhane (On farming, tools and agricultural systems in Azerbaijan) Azerbaijani Ethnographic Collection, 2nd Issue, Baku, 1965.

A.S. Pushkin, Puteshestviye v Arzerum (Journey to Erzurum), Collected Works, Volume 2, 1937. I.I. Kalugin, Issledovaniye sovremennogo sostoyaniya zhivotnovodstva Azerbaydzhana (Research into the current state of stock-rearing in Azerbaijan), Volume 5, Baku, 1930.

Georgian Central State Archive

International symposium on oriental carpets, thesis and papers, Baku, 1983.

SMOMPK, 9th Issue

A.S. Vartapedov, Ocherk zhilish i kadrov Nagornogo Karabakha (Outline of dwellings and people of Mountainous Karabakh), material from a visit to Karabakh in summer 1933, AzFAN, Baku 1936.

Q.V. Urazov, Mediko-topograficheskiy ocherk Jebrailskogo uyezda Yelizavetpolskoy gubernii (Medical-topographic review of Jebrail district in Yelizavetpol Governorate), Medical Collection, issued by the Caucasian Royal Medical Community, Tiflis, 1889, No. 50.

Obozrenie Rossiyskikh vladeniy za Kavkazom (Review of Russia’s Transcaucasian possessions), St Petersburg, 1836.

M.N. Nasirli, O nekotorikh napitkakh Azerbaydjana (On some drinks of Azerbaijan), Azerbaijani Ethnographic Collection, 1st Issue, Baku, 1964.

A.K. Alakbarv, Issledovaniya po arkheologii i etnografii Azerbaydjana (Research into the Archaeology and Ethnography of Azerbaijan), Baku, 1960.

R.A. Huseynov, Ob ustoychivosti i preyemtstvennosti traditsiy svadebnikh obryadov u narodov Predney Azii (On the durability and continuity of marriage traditions amongst the peoples of Near Asia), Papers of Eastern Commission, VGO, 1st and 2nd issues, St Petersburg, 1965.

.jpg)