More than 20 years after a fragile ceasefire was agreed between Azerbaijan and Armenia, tension continues to simmer on the front lines of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Away from the front line the psychological impact of the war fought in the early 1990s continues to interrupt the lives of thousands of families whose relatives disappeared during the conflict and have since been labeled “the missing.”

The Missing

The International Red Cross estimates that some 4,500 people are still missing from the Nagorno-Karabakh War, 3,700 of whom were registered by its delegation in Baku. Azerbaijan’s State Commission on Prisoners of War, Hostages and Missing People had 4,018 citizens registered missing at 1 November 2015. The fate of these people remains unknown; they are caught between life and death.

For many of their families, the uncertainty surrounding the missing makes it worse than knowing a loved one is dead. They remain trapped between fading hopes that the missing relative is still alive and the immense difficulty in accepting, without evidence, the likelihood of their death. Meanwhile a generation has grown up without fathers or mothers, husbands or wives, brothers or sisters, with financial and legal difficulties and a deep sense of loss. Thousands are frozen in eternal waiting, unable to move on, until they have some confirmation to say “alive” or “dead.”

My husband woke up one morning and said he was delivering weapons to the front line and would be back in two days. Those two days have become 22 years, said Reyhan, whose husband went missing in 1994.

Enter the ICRC

Since 2012 the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has been introducing and expanding a programme of emotional and psychological support to families of the missing, based on group therapy and individual family visits by mentors or “accompaniers,” themselves with missing family members and trained in counseling by the ICRC.

The programme has a regional and cyclical approach. It started in Baku and has since moved into Azerbaijan’s regions (ICRC offices in Nagorno-Karabakh and Yerevan are implementing an identical programme).

The main aim, according to the ICRC, is to help families cope with the psychological and social consequences of the disappearance.

Each cycle lasts for six months, during which families are invited to peer support groups to talk about their pain and the related financial, health and administrative issues caused by the disappearance of relatives.

they are caught between life and death

Between 2008 and 2011 the ICRC jointly with the State Commission on Prisoners of War, Hostages and Missing People and with the support of the Azerbaijan Red Crescent Society, collected detailed data using questionnaires to record as much information as possible about the missing relatives. Another initiative was launched in 2014 to collect biological samples from family members, which could be used to identify remains in the event of future exhumations.

But until greater clarity can be given to the fate of the missing, much of the ICRC’s work focuses on helping family members to share the grief and related difficulties that has been locked within for over twenty years.

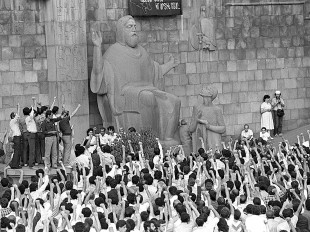

Missing in Khojaly

From Farida Jabbarova’s soft features and infectious smile you wouldn’t guess that she had witnessed one of the worst tragedies in recent Azerbaijani history – the massacre by Armenian forces of 613 inhabitants of the village of Khojaly in February 1992. It was in Khojaly that her husband Azad went missing and 21-year-old Farida was left alone with her two young boys. Her eyes filled with tears as she cast her mind back to a cousin’s funeral about two years after her husband’s disappearance.

Some families have become so close, she noted, that the ICRC gatherings have led to several marriages

A soldier named Azad, the same name as her husband’s, was spotted returning from the frontline and everyone was enormously relieved to see him coming home in one piece. No one more so than Farida’s four-year-old son, who came running towards his mother, jumping over all the other women in the room. Mum, I swear, Dad is back! he cried, convinced this soldier was his father. Knowing it wasn’t, the women began to weep – the depth of the young boy’s pain of growing up without a father was so plain for all to see.

I would say the problem of the missing is the hardest part of the whole conflict, Farida said.

The case of Garadagh

Garadagh is a sparse, industrial region of southern Baku, beyond the expansive oil fields and jagged cliffs of Bibi Heybat. Its large territory and thinly spread population meant that the 84 families of the missing living there hadn’t come together until accompaniers such as Farida contacted them regarding the ICRC family gatherings. The result, according to Farida, was that mothers and sisters began to leave their homes and to socialise with others suffering similar tragedies. On a personal level, Farida has become more independent and made countless new friends. Some families have become so close, she noted, that the ICRC gatherings have led to several marriages.

From Farida Jabbarova’s soft features and infectious smile you wouldn’t guess that she had witnessed one of the worst tragedies in recent Azerbaijani history

The 84 families in Garadagh were divided into three groups for the purposes of the programme. Farida, a trained nurse, has worked with about 30 of them. She admitted to being unprepared initially, despite being a Komsomol leader during Soviet times, but she received training thanks to the ICRC and learnt to approach families and offer emotional support. The Azerbaijani Association of Psychologists, which partnered the ICRC in the programme, and especially its president Elmira khanim also offered close support.

Farida now makes the initial contact by phone and explains the programme step by step. She conducts a short psychological and economic survey and suggests that the family attends a local ICRC gathering, which happens twice a month during the six-month cycle.

A few families said they didn’t need anything, Farida said, but 80 per cent were waiting for something like this.

The gatherings provide a unique space where family members can share the pain that may not have been understood or accepted by those on the outside.

“Look in the mirror!”

Battling tears, Farida focused on two of the thousands of personal stories she has encountered as an accompanier. The first concerned a mother from Fuzuli who went to search for her missing son in a forest near Aghdam, where he was thought to have disappeared. Her husband and another son accompanied her and they stayed with a local family. One evening she went to bed and when she next got up, she was met by everyone’s utter shock and surprise. Look in the mirror! they said, and when she did she saw that her jet-black hair had turned completely grey overnight.

The second experience concerned a young man called Mehti who would often tell his mother how much he loved the expression “wife of my brother” (sister-in-law in English – Ed.) and dreamt about his younger brothers getting married. When the brothers eventually arranged to get married on the very same day, 10 years after their elder brother’s disappearance, their mother didn’t want to have any part; she hadn’t been to the girls’ parents to request their permission and she didn’t dress up or follow any of the normal traditions.

Her sons begged her to come to the wedding and reluctantly she did. But on the way to the marquee she heard her missing son’s voice – Mum, we had a deal, how could you go without me? The woman dashed home to fetch a photo of Mehti, put it under her jacket and returned to the wedding, where she got up to dance. Without thinking she took the photo out and began dancing alone with her son.

Everyone stopped, Farida said, including the musicians.

“Two days became 22 years”

The depth of pain surrounding the missing became all the more visceral when I met Reyhan Janiyeva, another accompanier who has worked on ICRC programmes in the Garadagh district of Baku and the Salyan and Neftchala regions of Azerbaijan. Reyhan’s husband Sakhavat, an engineer from Salyan, was a tank commander during the Karabakh War who went missing near Fuzuli in 1994. Reyhan (28 at the time) was left to raise two young daughters.

Although well supported, living with her parents, brother and sister and working as a primary school teacher, there was little space to grieve - she didn’t want to burden others and felt her pain wouldn’t be understood. Instead she would shut herself away in the laundry room for a few hours once a week to cry alone. She would cry at night too, to the extent that by morning her pillow was soaked through, and at the school, where she taught a young girl whose father had been martyred during the war. I would look at her in class and cry, she said.

For many years Reyhan told her daughters that their father was in Russia to protect them from the truth. But then one day, about seven years after the disappearance, a teacher let slip to her eldest daughter (aged 11) that her father was amongst the missing. Her daughter raced home and demanded – Tell me the truth!

| The Red Cross is a non-political organisation working to reduce the effects of the Nagorno- Karabakh conflict. In its 2014 newsletter, the ICRC noted the following: In 2014 the accompaniment program covered 19 districts of Azerbaijan and reached 910 families of missing persons. Twenty-eight family members were selected and trained as accompaniers and 631 people received emotional support through emphatic listening which allowed persons in distress to express their feelings. Out of them, 407 persons regularly participated in the abovementioned peer support group sessions and 224 people received individual home visits. In addition, 60 families were referred by the accompaniers for legal-administrative needs, of which six families were able to apply for and receive Shaheed [“Shahid” or martyr – Ed.] status for their missing family members. |

My husband once said out of the blue – “If anything happens to me, just promise that you will give our daughters an education,” said Reyhan. In my daughters’ eyes you can see the deep, deep pain. I do my best to give them an education and I don’t want them to suffer, but I know they do.

One day she found them measuring an old jacket and trousers belonging to their father, just to see how tall he was.

Hope & despair

Reyhan still hopes that Sakhavat is alive. Many families, she says, continue to believe their loved ones were captured and detained and some day will return. As Farida had said, there were cases following World War II when the disappeared had suddenly reappeared up to 20 or 30 years later. But linked to this hope is the fear that the loved one could be suffering somewhere:

I am suffering, but I am free. But what about my husband, if he is in prison somewhere? Said Reyhan.

In the meantime they wait … eternally, torn between hope and despair. Both Farida and Reyhan spoke of young women whose fiancés or lovers had gone missing and refused to marry anyone else, still waiting for them to come home. There was also the mother who wouldn’t touch the 200 AZN monthly pension she received because she planned to spend it all on a grand party upon her son’s return, and the spacious two-storey house in Salyan that belonged to a missing person but neither the brothers or sisters had decided to move in. Their brother would surely return.

The other recurring theme surrounding the missing is the absence of graves. Whereas relatives of the shahids (“martyrs” or those confirmed died whilst fighting) can visit a concrete gravestone to pay their respects, families of the missing can only congregate around old photographs, objects and clothes.

Reyhan has managed to find out certain things related to the disappearance of her husband Sakhavat. During a gathering of families in Salyan, she listened to a father talking about his son’s disappearance in Fuzuli, describing the territory and even the hill where his son’s tank was last seen. And then suddenly a detail of the tank sparked her attention; it had the words For the motherland, for Heydar Aliyev! scribbled in Russian on the side. Sakhavat had studied in Rostov and wrote in Russian. He would have written this and so this man’s son must have served in the same tank.

Reyhan’s family travelled a lot to the areas where the battles were fought. They made every effort to find some information about Sakhavat’s fate. A veteran tracked down by Reyhan’s family in Goychay offered a little more clarity; he had also served in Sakhavat’s tank. According to him, their tank had gone into battle against the Armenians, been hit and burnt to the ground along with everyone inside. Only the veteran from Goychay had managed to jump out along with one other, who was captured by the Armenians. But he couldn’t (or didn’t want to) say who this was, if indeed this really was true. Many returning soldiers would protect families by hiding the truth.

Real support

The ICRC support programme and her work, as an accompanier and a teacher, had saved Reyhan’s life just at the right time. A few years before joining the programme, she had had an operation for cancer and was told she wouldn’t have long to live. Then her mother mentioned an ICRC gathering in Alat, which would ultimately change her life.

During the meeting she broke down – Bring back my husband! she cried, I need someone to look after my daughters. She was then invited to the offices of the Azerbaijani Association of Psychotherapists, who accompanied her to a post-operation check-up. There was no sign of cancer and soon after she was fulfilling her long-held dream of having contact with other families of the missing by working for the ICRC.

her jet-black hair had turned completely grey overnight

Reyhan visited the families together with another accompanier and emphasised how important it was for families to make contact and get to know each other: sharing difficulties makes them easier to bear and sharing joy makes it all the greater, she said.

Nonetheless there were a few stories she would never forget, like the mother who after an hour of talking lifted her mattress to reveal a shirt and a pair of trousers belonging to her missing son. I can smell my son, she said, without this smell I can’t sleep. Similarly, another mother kept her missing son’s jacket hanging by the light switch so she would touch it every time she turned it on.

What did we do to the Armenians for them to do this to us? Reyhan concluded, her face streaming with tears.

Beyond emotional support

Problems relating to the missing encompass financial and legal difficulties too. In many cases, the missing relative was the breadwinner and families can’t receive a state pension on their behalf unless they have been registered as dead. But, naturally, registering the missing relative as dead is a huge psychological challenge.

According to Farida, the ICRC addresses this by offering additional non-psychological support for families such as free treatment and check-ups through a partnership with the Iranian Red Crescent, as well as essential items like heaters and ovens – small things that help the families to survive. Reyhan noted that she still received calls well after the programme cycle had finished, particularly from the elderly, with requests ranging from organising pension cards to enrolling children in school.

Moreover, Farida was already helping to collect biological samples of families in Baku as part of a programme the ICRC plans to extend to the regions soon. DNA profiles can be generated and filed from the samples, and used to identify remains if political will allows for exhumations in the future. Meanwhile, Reyhan believed the main thing was for families to keep in touch and support one another after the ICRC gatherings have finished.

That somebody wants to know and is interested – this is a huge thing for us, she noted.

After all, until there is a resolution to the conflict and until there is a thorough investigation into the thousands that remain unaccounted for, despite the best efforts of the ICRC and their partners, the fate of the missing is likely to remain a painful wound that refuses to heal.