Meeting Mustafazadeh and Magomayev

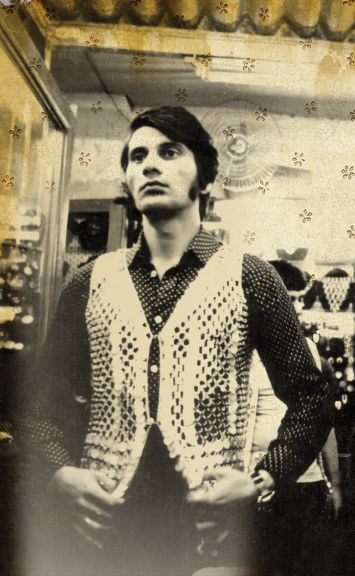

Far from the usual heat of mid-summer Baku, I’m driving down a once familiar road to my grandparents’ Zira country house. Years ago, it seemed like every house, every fence, every tree was bigger than it appears now. It was 3.30 in the afternoon when I parked outside the gates. My grandmother was the one who opened the door, with her little dog too excited to see a new person. It was the usual naptime for my grandfather, one thing that hasn’t changed in the years that I’ve known him - the one hour of sleep every day.

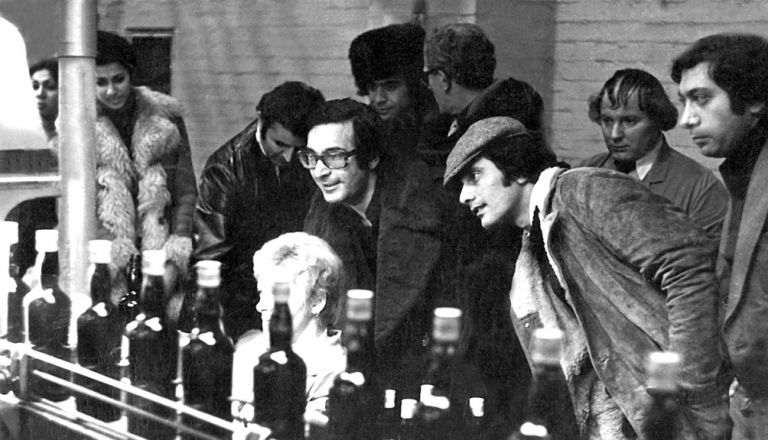

While we drink tea and unbox the photo archives that they’ve accumulated, I look around and realise that although I haven’t been here since the renovation, it still feels like home. I guess it’s the familiarity of the objects in the rooms. I remember it always felt a bit like being in a museum, surrounded by numerous cultures, most of the objects being souvenirs from all over the world. Interestingly enough, the foreignness of all these objects made the place feel more homely for me.

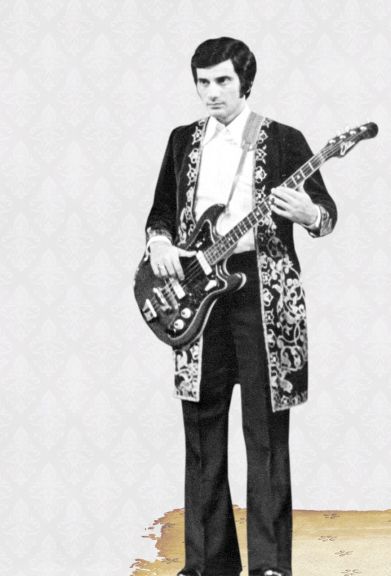

There are so many things about my grandfather, Rovshan, that I know, but never really acknowledged or gave any credit to him for, as I would normally for any other musician with the same experience. He is a very self-contained man, he always has been. He doesn’t talk excessively, but when he does, I want to write down his every word. He has a very precise regimen. After all the gigs played around the world, he still has an hour of rehearsal everyday, “to keep the fingers warm.”

He doesn’t talk excessively, but when he does, I want to write down his every word

Born in Baku in 1941, the third of four children, he showed talent in music quite early in life. Before starting school, during summer months at the Absheron Peninsula camp, he would often grab a trumpet and start playing tunes that he knew. He had already finished the first grade when my great-grandmother made a decision to transfer him to a specialised music school linked to the Azerbaijan State Conservatoire. He had to go into the first grade again, which is important to mention, since three years later this was the exact class to which the legendary jazz pianist Vagif Mustafazadeh would transfer, and another year later they would be joined by the great singer Muslim Magomayev.

Vagif Mustafazadeh & jazz development in Baku

I discovered the magic of Mustafazadeh and Magomayev years before this conversation ever happened. I remember the first time I heard March and thought there was something special about how the tune resonated. I started to look into his compositions and each one I heard made me a complete admirer of Vagif’s talent. It was the same story when I heard Melodiya (“Melody”) by Magomayev.

It is only natural to seek more information about people that fascinate with their ability to make their audiences not only hear but also feel the music, but, randomly picking Azerbaijani musicians for my iPod, I had in no way imagined that I actually knew someone who would tell me more than any book ever could. It is still surreal to place all three of them together in the same classroom.

Casually calling them by their first names, my grandfather recalled:

Muslim had just recently come back to Baku and was placed in our school. Vagif and I, they called us daredevils. He used to live in ‘the fortress’ (Icherisheher, Baku’s Old City – Ed.) and the youngsters there were always tough. I was also from the same kind of neighbourhood. Maybe that’s why we became friends at once. Like anyone at that age, we didn’t really like ordinary school. But the music education was always a good standard. At about 11 or 12 we were drawn to jazz, which might seem weird because at that time there wasn’t any jazz music in all the movie theatres and dancing halls, only pop. Only later, a fusion of jazz and pop started to reach the general public. This fusion started to occur shortly after the war, when “trophy” movies were brought to the [Soviet] Union - “Sun Valley Serenade” is one example. As American movies spread throughout the [Soviet] Union and Azerbaijan, so did the knowledge of jazz.

As American movies spread throughout the [Soviet] Union and Azerbaijan, so did the knowledge of jazz

We were drawn to this style of music before there was any material, information or records available. We were listening to the radio show “The Voice of America” at night. It aired after midnight and went on for about 45 minutes. It was a single broadcast about jazz at the time. Since there was no jazz education, we tried to remember everything we heard during those 45 minutes. We would listen, analyse and repeat everything from that radio show. We were moving fast because Vagif had absolute pitch, he could memorise, perfectly recreate and determine any existing sound. We even had a game among friends, throwing different coins, big and small, heavy and light, and Vagif would accurately detect which note each coin sounded when it hit the floor. We would then come to the grand piano and check. He was right every single time.

We would spend hours in their apartment, practising, playing around with ideas. The jazz-mugham fusion started as a game. Mugham is very improvisational in its nature, just like jazz, so it was only natural when one day Vagif said, “Here, look what I did here ... you hear the Bayati Shiraz piece in the middle of which we were working on yesterday? What do you think?”

The jazz-mugham fusion started as a game

Our material was piling up and as time went by, we were invited to perform. Back then it was prestigious for people to invite musicians to their homes to play live music. So we started to go together, just the two of us, still young boys. After the 8th grade, all three of us (Vagif, Muslim and myself) decided to transfer to the Azerbaijan State Conservatoire, because it gave us a professional diploma and a chance to get onto the stage faster. We were often performing in competitions and festivals, each one of us getting various awards and becoming laureates. When we were a bit older, we were invited in groups to different school events and holiday evenings. We were about 15 or 16 then.

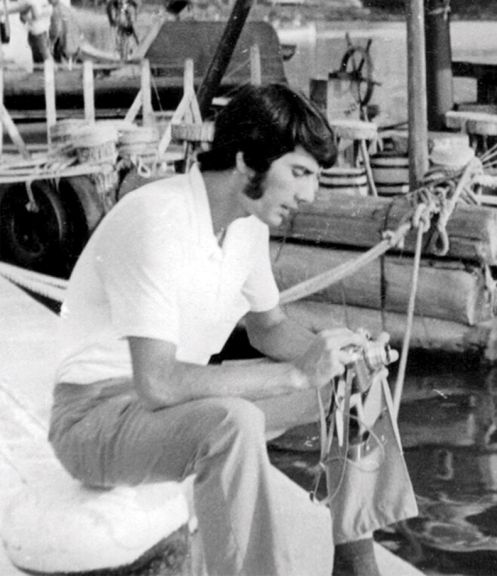

After we finished school, we usually performed at different venues and rarely saw each other. Then I was drafted to a naval base in Feodosiya [a town on the Crimean Black Sea coast – Ed.], where I spent four years. When I came back, again, due to our schedule overload, we saw each other rarely. He already had his own band and I had mine. On those rare occasions that we managed to meet, we would often talk about working together, as we did when we were just starting, but life seemed long and opportunities limitless. We never played together after the school years.

Rashid Behbudov

Fast forward to Kemerovo, where a telegram from Rashid Medjidovich Behbudov found my grandfather, inviting him to join the Song Theatre in 1971.

It has taken me several trips to record my grandfather’s most prominent tour stories, and there were still a great many that were carefully camouflaged in the corners of his memory. Only now do they begin to make sense on a completely different level.

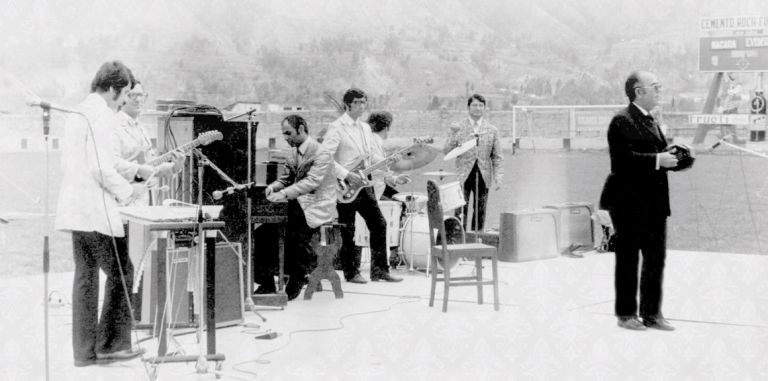

Looking back at my musical career, I can say that I am truly a lucky man to have such wonderful collaborations with my friends, one after another: my very first performances were with Vagif when we were still boys, then with Rashid Behbudov for more than 10 years [the group included such prominent musicians as Yuriy Sardarov, Sergei Krasnyansky, Rafig Babayev and many others]. Years later, after Rashid Medjidovich retired, I transferred to Muslim’s band.

I have to admit that although I have heard some of Rashid Behbudov’s songs, I did not really know much about the legendary singer, with whom my grandfather worked for more than 10 years. From the way he speaks about Rashid muellim, I get a sense of greatness and the tremendous respect that each member of the band had for him. I gather that Rashid Behbudov to this day holds a special place in my grandfather’s heart and memory.

For me, Rashid Medjidovich will always stay a great man, to whom there wasn’t, isn’t and probably won’t be an equal. Not only was he a professional performer, but he also possessed such humane qualities that I haven’t seen in a lot of people.

When I arrived in Baku, we rearranged the band, I finished the [concert – Ed.] programme and we went off on tour. The first destinations were the Northern Caucasus and Central Asia.

We were moving fast because Vagif had absolute pitch, he could memorise, perfectly recreate and determine any existing sound

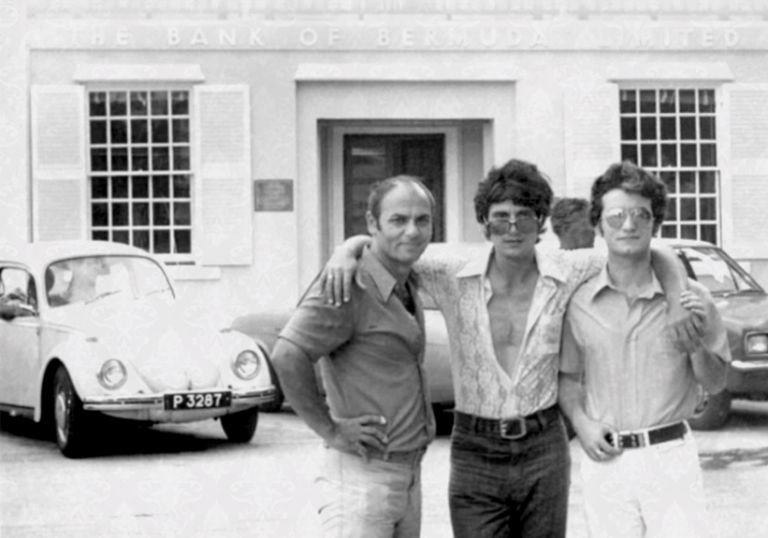

From 1972, The Song Theatre started touring worldwide. We were representing Azerbaijan and the Soviet Union. Among the first places we visited in Europe were Hungary, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. Everywhere we went the concerts were a tremendous success. Legends about Rashid’s concerts were around even when I was a child and there were thousands of people waiting for him in every town; his car was lifted off the ground several times. And there I was, witnessing this man’s legendary success. It was incredible.

I can hardly wrap my mind around all these names: Behbudov, Magomayev, Mustafazadeh, Babayev. Those are the jewels of Azerbaijani musical culture that are, sadly, no longer with us. And despite their acknowledged input to our cultural heritage, we still have a very limited knowledge about their lives as they were building those unbelievable careers. Talented musicians of this calibre might seem to be unattainable, glorious geniuses, and rightfully so. However, during our conversation, I get the impression that all these people who seemed so unattainable were just a big group of friends making music, travelling, joking and exploring life’s opportunities.

Seeing pictures from such remote locations as Bolivia, Chile, Argentina made me wonder how travelling there was even possible at that time. But it’s quite easy, he explains. We were the only musical collective in the [Soviet] Union that was performing this particular type of music, and of course, the incredible voice of Rashid Medjidovich played an important role in the band’s worldwide concert invitations.

I’ve been hearing these same tour stories ever since I was a child, but only now do I understand the importance of each one, pieces that transform their lives into a fuller, more detailed picture - all the dangers of Chile and Argentina [prior to the 1973 Chilean coupd’état – Ed.], the hard concerts in Lima, their meeting with the then Chilean president Allende, and simple everyday situations that showed the great character traits of the band members. I look at the man that used to be just my grandpa and I’m in awe. I wonder, intrigued, if the quiet life he’s leading now is enough for someone who has had such a great journey in life. After finishing the concert tours with Magomayev, my grandfather Rovshan lived and worked in Turkey for about 5 years. Judging from the pictures that sit in a plastic bag right next to me, he had a life full of adventures, travels, fun times and scary times and it still doesn’t add up in my head that this same person would sometimes meet me from school.

As I begin to write down my grandfather’s memoirs of concert tours around the world, I see him beginning to re-live those experiences in his head while he looks at the wind moving through the branches of a huge apricot tree. And it began to make sense that this might be exactly the life a musician might want after such a long and bright career, but with a reserved man like him you never quite know. Inspired by the beautiful nature, my grandfather still writes music, has several students and performs evening gigs in downtown Baku a couple of nights a week.

Tour stories? Are you sure you have enough space on your tape-recorder? He asks, amused. I guess we’ll have to start with the Latin American tour, the most dangerous one I remember. It was in the time of president Allende…

Stay tuned for more to come in the next issue of Visions …