Is ‘art for art’s sake’ or is ‘art for business’? Art historian Mohbaddin Samad found a clash between the two when he uncovered the trail of an unsigned painting from Baku to Paris.

Observe Paris from the top floor of the Eiffel Tower and you will see the entire city. At night, lit up, it looks like a giant chandelier. The flowing River Seine and endless Avenue des Champs-Élysées, with its elegant buildings and Arc de Triomphe, enrich the heart of this cosmopolitan city.

Paris is one of the most beautiful and most expensive cities of the world. You need a lot of money and it’s not an easy place to live. However, there is a continuous influx of people from many countries; people of various races and nations live in Paris. Despite the difficulties, they are happy. I saw it in the face of journalist Edith Domarkaite, originally from one of the Baltic states, who works for a French newspaper.

Edith loves Paris. She knows all the corners, streets, squares, antique shops, museums and cafés of the city. She likes paintings, literature and music, and is a published author on world art.

We met in Paris three times: first in 1996, then in 1998, and the third time in 2000. She was my most valuable guide to the Louvre, Georges Pompidou and Decorative Art museums and famous antique shops. Through her, I discovered carpets, jewellery and folk art, most memorably at antique shops on the Avenue des Champs-Élysées and Rue Honoré de Balzac and at Louvin, a private gallery. And then, the painting at the centre of this story, at the private gallery of Monsieur Aynard, a painting entitled Landscape.

Artist unknown

Landscape is as beautiful as it is fascinating – there is no signature, no date, nor any note of attribution. So, who painted it?

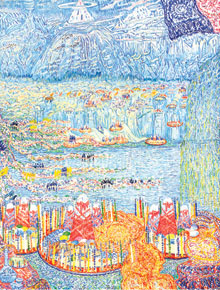

When I saw the work for the first time in 1996, I associated the colours, style and artistic spirit with great Azerbaijani artist Sattar Bahlulzade.

At the time I didn’t mention it, because Sattar Bahlulzade imitations were always popping up in Azerbaijan. I saw more than 20 ‘Sattar’ artworks hanging in the corridor at the editorial office of Azerbaijan newspaper – very convincing until further inspection. That is why I wanted to find the identity of the unknown artist without much attention. In this, Edith was my most helpful assistant.

The start: Monsieur Aynard’s gallery

Where did this painting come from? Who bought it? Who painted it? Edith translated my questions for Aynard, who only grew irritated by us: You’re wasting my time, you’re stopping me working. This isn’t business. If you want to conduct studies or research, you should go to the state museums.

Edith, familiar with the business psyche, continued: Monsieur Aynard, you know me very well, and you have made a lot of sales through me. If you can tell me what I need to know, it may well be worth your while, as it usually is…

Aynard’s expression changed. It may well be worth your while. He was no longer the angry person of a few minutes ago. He turned to Edith and said carefully: We don’t have any information about where this work is from and who the artist is. But it was presented to us by someone named Georges who used to work as a photographer at the French Ministry of Culture. Now he is 80 years old, cannot hear very well, and his legs are bad. He does not leave the house. I have his home phone number and his address.

Chez Georges

The next day, there we were, sitting at an old dining table in Georges’ second floor apartment on Rue Balzac. He used a walking stick, wore a hearing aid and looked very pale because of staying indoors, the unfortunate trace of a lasting illness.

Edith, realising a long discussion would be impossible, had got straight to the point: Monsieur Georges, in Monsieur Aynard’s collection we saw a painting called Landscape. He said that it came from you. Can you say where you got it from?

Georges disliked Edith’s pointed question: Why, am I on trial?

Edith responded smiling: Of course not, we’re just interested in the story of this artwork. But Georges had questions of his own: Where are you from? Why do you want to study this work? And what do you want from me?

Edith, still smiling, replied: We are writers. I live in Paris and work at one of the French newspapers. My guest is from the former Soviet Union. He lives in Baku and works at state television. Georges thought for a while, and answered: I am too old now. My memory is not good. To give you a precise answer, I would need to study my archives. That takes time.

I could not hold back and said: Monsieur Georges, I leave for Baku tomorrow. Please can we study this now.

Georges thought for a while, and called to his wife: Suzanne, would you bring my archives from the late 60s?

Answers in the albums

Suzanne appeared, first with coffee, then her husband’s photo album. These photos are essential in solving the puzzle, because, although the location and the author are unknown, they are both recorded in my photos. You will recognise the artist and will know if this work is his.

This suggestion was reasonable, so we patiently turned the pages. Soon we saw photos of Baku: meetings between French and Azerbaijani cultural workers, artists’ studios, photos of their paintings, close-ups. In a moment, all became clear. I felt optimistic. Photographer Georges, with his sensitive profession, felt it immediately, and smiled: It seems you’ve found what you were looking for?

- Not quite, Monsieur Georges, thank you very much. But we still need to know the story of how this painting came to Paris. Can you tell us?

Georges was reluctant. He said he was ill and tired. As was her way, Edith began kindly: Monsieur Georges, your trade is a humane one. You always tried to bring happiness to people. And you achieved it in the past. Now, you are no longer a photographer, but you do have memories. Do you know how many millions of people you will bring happiness to if you share with us your memories of your official visits to the former Soviet Union, to Baku?

Moved by this, despite the late hour, Georges began his story from afar: For many years I worked at the French Ministry of Culture as a photographer. I joined delegations on their visits abroad. In 1969, we were invited on an official visit to the Soviet Union by the former USSR minister of culture. André Malraux was the French minister of culture at that time, leading the delegation. He was also a famous art critic and writer, author of numerous literary and academic books.

A visit to Azerbaijan

After formal business in Moscow, we travelled to Baku. It was a very interesting city, oriental, built on a synthesis of antiquity and modernism. We visited the Museum of History and Museum of Art, took a boat on the Caspian Sea, and were taken by the minister of culture to the studios of two famous, extraordinary and interesting national artists; first, Togrul Narimanbeyov [Narimanbekov].

André Malraux had seen original works by Cézanne, Renoir, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Modigliani, and was absolutely charmed by the artist, his paintings a fusion of ethnocentrism and internationalism.

As official photographer, I was snapping people eating, talking, and the art, and André Malraux in conversation with Togrul. Everyone was tucking into walnuts, almonds, hazelnuts, pakhlava and shakarbura, washed down with champagne. Presently, André Malraux looked at his watch and said kindly: “This is wonderful, I do not want to leave, but I’m afraid people are waiting for us elsewhere. We must thank you and say goodbye.”

All delegation members stood up and got ready to go. At this point, the painter went to the back, took one of his painted panels, returned to the front and presented it, smiling: “Monsieur André Malraux, this is a souvenir of your visit to my workshop. May the cultural relations between France and Azerbaijan be strong.”

A delighted André Malraux hugged the artist before bending to write in his visitors’ book: “The works of Togrul Narimanbeyov are of great value. They create a rare synthesis of Eastern and Western cultures.”

I recorded every moment of this meeting. By the way, I should say that such an absent-minded person as me would never have remembered the name Togrul Narimanbeyov. I only remembered it because of his signature on his painting to André Malraux and because the minister wrote the name “Togrul Narimanbeyov” at the beginning of his entry in the visitors’ book.

Georges continued. I don’t remember the name of the second painter. None of his works were signed. I checked on the photos I took. However, he had a very memorable face: cracked as if dehydrated, bronzed by the sun. He had big grey eyes, and his long grey hair fell on his face giving a strong ‘painterly’ look. This artist, who looked calm, was very impetuous inside. We could tell from his landscape paintings.

André Malraux was enchanted by the beauty of these works, looking at every painting, and commenting to the USSR deputy culture minister, Vladimir Popov, as I filmed: “This painter developed in the climate of Realism, but it’s as though he graduated from the French Impressionist school.”

Then we ate from an eastern-style table stacked with almonds, walnuts, red dates, raisins, apricots and figs. We drank tea from the samovar urn and pear-shaped glasses on a silver tray. After that came the speeches: the Azerbaijani minister of culture noted the artist was a peerless master of landscapes; the USSR deputy minister of culture, Vladimir, Popov, discussed the important friendship between France and the USSR. Then André Malraux gave a speech. Although his was political and diplomatic, it was very meaningful: “Dear friends, you well know that France is a highly cultural country. It has borne poets, singers, artists and writers of genius, such as Victor Hugo, Honoré de Balzac, Guillaume Apollinaire, Charles Baudelaire, Cézanne, Paul Éluard, Edith Piaf, Renoir, Gauguin and Van Gogh. The Louvre is the most attractive museum in the world. There is no doubt that we French are proud of all this. We are also glad to witness its collaboration with other countries.

“During this trip, I have seen how art in Azerbaijan is rapidly developing. Both artists have left a marked impression. They are extraordinary painters, worthy of their nation’s pride, and of international recognition.”

Georges turned the pages of his album, before stopping at one of the painter: This photo was published on the cover of one of the most famous art journals in France. I received the Photographer of the Year award for this photo.

The photo was of Sattar Bahlulzade.

After tea came the ceremonious present-giving, and the artist gave his works to Vladimir Popov and André Malraux. Just as we prepared to go, the painter came to me and, with the help of a translator, presented another painting: “And this work I give to you, because you worked hard and I like you.”

The truth

From the very beginning, before seeing these photos, I had said that the patterns, style and colours were Sattar Bahlulzade’s. However, having seen Sattar’s imitators in Azerbaijan, I hesitated before making a final judgment. I’m closer to being sure now. However, I do believe that I also need the opinion of Togrul Narimanbeyov who is very familiar with Sattar’s work.

Edith followed on from me: But how did your painting get into Aynard’s private collection?

This question was like salt on a wound. Georges’ face changed, his muscles strained and his hands began shaking. He refused to talk, claiming it was too late and he was sick and tired. But Edith pressed: Monsieur Georges, I understand that you are tired. Let’s have coffee and rest for a while, but not abandon our conversation, because our guest is flying back to Baku tomorrow. We want our guest to remember Paris and Parisians in a good light, not bad.

Georges replied: You know, some things in a family should remain private. This work Landscape is one of those things. Why we sold it and at what price, is none of your business…

Edith interrupted Georges: Monsieur Georges, we are not here as police investigators but as guests. Our aim is to find out who painted Landscape and how it came to Paris. You have helped a lot, thank you. My friend will write many good words about you, he will mention your name, and introduce you to his friends and acquaintances.

At this, Georges seemed to soften. He took a few sips of coffee and continued talking, albeit impatiently: This work Landscape was everything to me. I never wanted to sell it. It was unique, raised my spirits. It brought a breath of spring into our home.

Well, I reached pension age and retired from the French Ministry of Culture. Two years later I fell ill. Doctors told me that I needed urgent surgery, otherwise I would get worse.

I am just a photographer; I do not have large financial means. That is why my wife Suzanne and I, after much deliberation, finally decided to sell Landscape.

We placed an announcement in the newspaper. About ten people came and offered to buy it, at various prices. Some saw the lack of signature and just left. One day, a rich American woman came. She liked the painting very much, and offered a much higher price than we were thinking of, but I did not agree to it.

You are probably wondering why not? Well, because she lived very far from us. I wanted the painting to go to someone who lived close by, so I could still see it sometimes. So I did. I sold it for 30,000 dollars to Monsieur Aynard. When I could still walk, I often visited his private gallery to see my favourite Landscape. I’ve not been for many years.

Despite our conversation with Monsieur Georges ending on a down beat, I was very satisfied. Now I just needed to meet Sattar’s close friend in Paris, Togrul Narimanbeyov. He could take one look at the painting and tell us. This took place on my second visit to Paris in 1998.

Confirmation

Togrul Narimanbeyov used to live in the USA but had moved to Paris. Soon we were both standing in Aynard’s private gallery together. As soon as he saw Landscape, he said: There is no doubt this is Sattar’s work. It’s his style in the late 50s or early 60s. If I am not mistaken, its name is not Landscape but Spring Song.

Then Togrul told me of another Sattar Bahlulzade painting that hung in another gallery, Louvin, called Old Tree, also painted in the late 50s. As Sattar’s signature was not on it, the gallery owner claimed the piece was by painter Martiros Saryan. Later I would go to the gallery and request that the name be corrected.

And how did this second work of Sattar reach a Parisian gallery?

Togrul smiled and said: Apparently he gave it to someone who brought it to Paris. There was no signature, so they presented it as work of the well-known Armenian painter Martiros Saryan and sold it to the gallery. People who do that are not like us. Our motto is “art for art’s sake”, theirs is “art for business”.

About the author: Mohbaddin Samad is an art historian and critic who has written widely on art, especially Azerbaijani art.