New borders, new ideas, enlightenment versus entrenched attitudes – the 19th century was a time of radical social and political change in Azerbaijan.

New borders, new ideas, enlightenment versus entrenched attitudes – the 19th century was a time of radical social and political change in Azerbaijan. The Russian Empire annexed northern Azerbaijan (including the present-day Azerbaijan Republic) and this was formalized in two treaties between Russia and Persia, the treaties of Gulistan (1813) and Turkmenchay (1828). In the north the division swept away government by the old khanates and replaced it with rule from Moscow. The split caused immense social upheaval and was in many ways a tragedy for the people, but at the same time it opened doors to the culture and ideas of Russia, Europe and the West.

Author and activist Mirza Fatali Akhundov was to make use of those open doors. He brought Western culture and ideas into Azerbaijani literature and public life, becoming a leader of the enlightenment movement and the founder of a new literary era.

Early life

Mirza Fatali Akhundov was born in 1812 (the exact date is not known) in the town of Nukha, now called Sheki, in north-western Azerbaijan. His father was from the village of Khamana in Tabriz province in Iranian Azerbaijan and his mother from Sheki.

Akhundov’s father Mirza Mammadtaghi and his grandfather, Haji Ahmad, before him were for many years the elders of Khamana and several nearby villages. In the early 19th century Mammadtaghi fell on hard times and, leaving his family in Khamana, went to Sheki to work as a merchant. In 1810 or 1811 he married Nana khanim, niece of Akhund Haji Alasgar, one of the best known Muslim clerics in Nukha, who was under the protection of the Sheki khans. A year later Fatali was born.

In 1814 Mirza Mammadtaghi returned to Khamana with his new family. However, the situation was very tough for the young wife because of constant conflict and quarrelling with Mirza Mammadtaghi’s first wife. Akhundov wrote in his Memoirs that after four difficult years in Khamana his mother left his father. She took her young son to Qaradagh province in northern Azerbaijan to the village of Horand to live with her uncle, Haji Alasgar. Fatali was under the guardianship of Haji Alasgar and was known locally as ‘Akhund Haji Alasgar’s son’ or Akhundzadeh, the Russified version of which is Akhundov.

In early 1832 Akhund Haji Alasgar was to go on pilgrimage to Mecca so he took Fatali to Ganja to study in the madrasa attached to the Shah Abbas Mosque. Akhundov had lessons in logic and theology and was taught calligraphy by renowned Azerbaijani poet Mirza Shafi Vazeh. A close friendship soon developed between Mirza Shafi and his student.

Mirza Shafi sought to discourage the now 20-year-old Akhundov from religious studies, encouraging him to study the modern sciences instead. Under Mirza Shafi’s influence Fatali gave up his religious and clerical education and began to study Russian in order to learn about Russian and European culture. He planned to work in the civil service in Tiflis (Tbilisi), which was then the administrative and cultural centre of the South Caucasus, and to continue his education with Russian intellectuals in the city. Far from trying to dissuade his adopted son, Haji Alasgar did everything in his power to help him. In the autumn of 1834 he and Fatali travelled to Tiflis and Akhundov was indeed appointed to the civil service.

Tiflis

Tiflis was a vibrant, thriving city at that time and beloved of the Russian imperial family. Mirza Fatali found himself amongst impressive, stimulating company there; he became friends with outstanding Azerbaijani writers Abbasqulu Bakikhanov, Ismayil Qutqashinli and Qasim bey Zakir and maintained his friendship with poet Mirza Shafi Vazeh. The founder of Georgian theatre, Giorgi Eristavi, Russian writer and exiled Decembrist Alexander Bestuzhev (Marlinsky), Polish revolutionary Tadeusz Lada Zablocki, Russian poet Yakov Polonsky and Russian orientalists Nikolay Khanikov and Adolf Berzhe all numbered amongst Akhundov’s friends. These relationships exerted a powerful influence on Akhundov’s views and interests and on his scientific and literary work.

Literary Realism, social activism

Akhundov is considered the first Realist author and playwright in Azerbaijan and the first literary critic. He was the first writer to use a Western form in an Eastern poem, On the Death of Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin, published in 1837, and later, starting in 1850, wrote Western-style comic plays.

Akhundov’s literary and public work nourished the spiritual development of the nation of Azerbaijan for more than 40 years. He earned renown as the outstanding theorist of the enlightenment movement and a major public activist, not only in Azerbaijan, but in the Near East as a whole.

Akhundov used the Russian scientific and cultural environment as a conduit to bring the democratic air of Western spirituality and culture to Azerbaijani literature. It was through the Russian language that Akhundov read European classic authors, such as Shakespeare, Molière, Voltaire and Montesquieu, as well as Russian ones, including Griboyedov, Pushkin and Gogol.

In the 19th century Azerbaijan’s access to the West lay through Russia, through Russian culture and literature. This changed in the 20th century, during the Soviet period, when political and ideological barriers cut off the Soviet state, in which Russia was the main centre of gravity, from the Western cultural and spiritual world. When this article talks about Akhundov’s relationship with the West, it implies his relationship with Russia as well as Europe.

In his landmark four-volume book The Literature of Azerbaijan, literary historian Firidunbey Kocharli recognized Akhundov’s work both as a social reformer and a writer: Mirza Fatali Akhundov was almost the first reformer of Muslims. He was the first person who destroyed the old, rotten fundamentals of Muslim life, struggled and struggled to change the rules which impeded the progress of Islam.

As for the comedies of Mirza Fatali, we can certainly say that he was the grandfather who led the way for Turkic-Azerbaijani writers and authors of comedies just as Gogol was the grandfather of Russian dramatists and Molière the grandfather and master of French playwrights. Our modern playwrights have not yet managed to write comedies to compare with Akhundov’s, not even Najaf bey Vezirov or Adburrahim bey Hagverdiyev, Nariman bey Narimanov or Mirza Jalil Mammadguluzadeh.

Akhundov’s plays remain well-loved. You can catch them at the following Baku theatres this year: The Botanist Monsieur Jordan and the Celebrated Sorcerer, Dervish Mastali Shah – Azerbaijan Drama Theatre, Young Spectators’ Theatre, Russian Drama Theatre and Puppet Theatre; The Adventures of the Vizier of the Lenkeran Khan - Azerbaijan Drama Theatre, Young Spectators’ Theatre and Russian Drama Theatre; Haji Qara - Young Spectators’ Theatre; The Unknown Akhundzadeh – Yug Theatre

Plays

Akhundov watched performances of Russian and European plays on the stage of the Russian Theatre which opened in Tiflis in 1845. This is where he learnt the art of drama. He then wrote consecutively six comedies, which were the first European-style Realist plays in Azerbaijan and the Near East. In the space of five years, Akhundov wrote The Tale of Mollah Ibrahimkhalil the Alchemist (1850), The Tale of Monsieur Jordan the Botanist and the Celebrated Sorcerer, Dervish Mastali Shah (1850), The Tale of the Bear that Caught the Bandit (1851), The Adventures of the Vizier of the Khan of Lenkeran (1851), The Adventures of the Mean Knight or Haji Qara (1852) and The Tale of the Defence Lawyers (1855). This constituted a real revolution in Azerbaijani literature.

The comedies took their subjects from Azerbaijani life. The action is set only in Azerbaijan. The types, characters, their way of thinking, dressing, speaking are all Azerbaijani. The language of the comedies too is based on the language of the people. It is living, natural speech.

Akhundov made good use in his work of his knowledge of European and Russian drama. Several characters and motifs in Akhundov’s comedies have similarities with characters from Molière and Gogol. Molière’s creation, Frenchman Harpagon in The Miser, and Akhundov’s Azerbaijani Haji Qara are both comic heroes, misers with local characteristics.

Monsieur Jordan

Akhundov made most use of Western characters in The Tale of Monsieur Jordan the Botanist and the Celebrated Sorcerer, Dervish Mastali Shah. Working on the basis of his own philosophical worldview and concept of Westernism in the comedy, Akhundov targets deceitful, ignorant, gullible people. He creates the character of the French botanist, Monsieur Jordan, in opposition to the dervish, Mastali Shah, who leads a life of swindling and sponging. Monsieur Jordan is presented as a representative of the world of progress, science, enlightenment and culture. Monsieur Jordan comes from developed, bourgeois France, while Mastali Shah comes from backward, feudal Iran. Through these two characters Akhundov creates a view of West and East in the 19th century. The representative of the West, Monsieur Jordan, serves scientific progress while the representative of the East, Dervish Mastali Shah, serves prejudice and scholasticism.

The Deceived Stars

In 1857 Akhundov published the novella The Deceived Stars, the first piece of Realist writing in Azerbaijani prose. The Deceived Stars is rich in biting irony and satire. The ironic ending presents the civic differences between East and West with great skill. In the story, the complex, important work of state management is entrusted to the predictions of deceitful, fraudulent astrologers. This is seen as sign of the backwardness of the East, where the main principle is not scientific and technological development but the ideology of superstition. The author concludes the novella with an ironic retort: I swear to God, they are strange fools this English tribe who almost began a war with such a dangerous nation.

In 1857 tension between Iran and England over Herat province almost led to war. While this military tension is a symbol at the end of the novella, the main function of this historical detail is as an artistic device to highlight the difference in thinking between society in the East and West.

Comedy is one of the most effective genres to depict in broad brushstrokes the realities of everyday life which give rise to discontent, to mock them and encourage audiences to mock them and stand up against them too. Akhundov used laughter as a corrective force and clearly showed in his own critical way the deformities in the society in which he lived.

As well as plays and a novella, Mirza Fatali Akhundov wrote articles and other material with social, ethical, economic or philosophical content. These include Three Letters from Indian Prince Kemal ud-Dovle to Iranian Prince Jemal ud-Dovle, Response to the Philosopher Hume, Dispute with Molla Alakbar, About a Single Word, Preface to a Book, John Stuart Mill on Liberty, On Rumi and his Work, On Maharram Mourning, Beliefs of Babylon, Story and The Sayings of Dr Sismond.

Alphabet reform

Mirza Fatali Akhundov sought ways to achieve progress and develop culture, following the example of Russia and the countries of Western Europe. Key to this, in his view, was education of the masses. He thought that such a major undertaking required first of all changes to the Arabic alphabet, which was used at the time to write Azerbaijani Turkish and Persian.

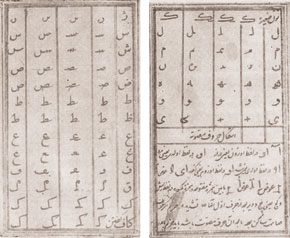

In 1857 he compiled a new alphabet on the basis of the Arabic one. The new alphabet better reflected the sounds of Azerbaijani Turkish and would be easier for people to learn. He sent the alphabet to linguists and Orientalists and to the heads of state of Iran and the Ottoman Empire and began a campaign for alphabet reform. As part of his campaign, he went to Istanbul in 1863 and presented the project to the Ottoman prime minister, Fuad Pasha. On the prime minister’s instructions, the project was discussed in the Ottoman Society of Science. Though the members of the society appreciated Akhundov’s initiative, they did nothing to introduce it. Meanwhile, Iran’s chief ambassador to the Ottoman courts, Mirza Huseyn khan, worked to scupper the project. He painted a negative picture of Mirza Fatali in Ottoman society as a hired missionary of Russia, an enemy of the Muslim peoples and Islam.

However, Akhundov did not despair at the failure of his project and did not abandon the idea of alphabet reform. He put greater effort and passion into the idea and developed a second draft alphabet, also on the basis of Arabic. Finally, he rejected the idea of developing the Arabic alphabet and drew up a new Latin alphabet for Azerbaijani Turkish. Akhundov’s interest in European scholarship and culture must have influenced his proposals for an alphabet based on Latin script.

Despite his years of work on alphabet reform, the Latin alphabet was not adopted in Akhundov’s lifetime. However, it became reality in the 20th century when it was adopted as the official alphabet of the independent Azerbaijan Republic. This was confirmation of Mirza Fatali Akhundov’s view that Azerbaijan would have to integrate with Europe and the West.

Both as an author and a reformer, Mirza Fatali Ahkhundov destroyed the dilapidated, outdated stereotypes and replaced them with a new, democratic literary life.

About the author: Sevinj Zeynalova PhD teaches English in the Foreign Languages Department of the Regional Studies faculty, Azerbaijan University of Languages. Is currently engaged in doctoral research on The Western Theme in Azerbaijani Literature.