The older generations of people living in the villages emanate a unique feeling which I identify as the essence of the spirit and culture of old Kavkaz (Caucasian) Azerbaijan. In sharp contrast, the younger generation and most of the people in the big cities, especially the capital, Baku, reflect modern western sensibilities more and more. Even so, there are quite a few young Azerbaijanis participating in the high art culture, especially the traditional music, who are able to express the old culture well.

But there is something about village life which imparts a quality, in combination with the unique culture that brings a clear, sharp sense of Kavkaz Azerbaijan which is very much alive even in this modern epoch. It is really a matter of degree more than kind. The people in the cities are still distinctly of Kavkaz Azerbaijani society even though they are no longer villagers who have kept alive that version of society pure and concentrated.

The arts always have a role to play in defining any society and Azerbaijan is no exception. The traditional music of Azerbaijan is enjoyed widely, even though many are now listening to Azerbaijani pop or the odd combination of folk tunes played on modern instruments set to a pounding back beat. I am curious to know if anyone has conducted surveys to measure how traditional some Azerbaijanis are in society and what kind of music they listen to. Meanwhile, one only has to attend a wedding in Baku or other city to appreciate what remains of their traditions and what has begun to give way to modern sensibilities.

I would guess that an Azerbaijani who feels part of traditional society would listen more to the old music than new music and might relate socially with another traditional Azerbaijani differently than with one who is less so. There is a cultural gap that cannot be bridged with all the politeness that even an Azerbaijani can muster. They would be relating to an Azerbaijani who has become thoroughly modernized and no longer shares the same values.

THE LORE OF WARMTH…

We have already encountered the notion that Kavkaz Azerbaijan is a society with an unusual degree of appreciation for outsiders, so much so that they will excuse a foreigner for behaviour that would be criticized in one of their own. Sometimes I can’t help but wonder if there is not some element of pity for the outsider, who may never be able to give and receive the exceptional warmth of a sincere Kavkaz Azerbaijani, manifested in the simplest of greetings. It is not the ritualized exchange famous in the Islamic world, although at first glance, if that is your prior experience, you could be excused for jumping to that conclusion.

Kavkaz Azerbaijanis, with a few exceptions in some isolated areas, are not oriented in life by Islamic scripture. The basis for their extraordinary hospitality and social grace is folkloric, not scriptural. It makes for a very informal and pleasant exchange between people of differing social strata. An amusing video clip comes to mind in which a little old Azerbaijani village lady had the gumption to confront the president of the Republic and dare to speak to him in that typical way that elder Kavkaz Azerbaijanis do that can be hysterically funny. The president was absolutely tickled by the old lady and her amusing request – help in finding a husband, preferably a rich one – in spite of the vast gulf between them. I should mention that there is a certain form for this, a recognizable syntax to the delivery that is rooted in ancient traditions. Perhaps the power of the discourse is in the formalism of its exposition. Spoken differently, it likely would not have been well received.

…AND RESPECT

…AND RESPECT

Of course, if someone younger were to attempt that, there would probably be repercussions, because in Azerbaijan the superior age of a person is held in high regard, regardless of one’s position in society. The extreme difference in social position between the president and an old woman villager was momentarily trumped by her advanced age, and all the president could do, surrounded by his bodyguards and a mix of local officials and villagers, was to laugh heartily at her humorous remarks. As she went on in that particular patter, the laughter increased and the amusement spread around until there was a kind of climax, a paroxysm of delight in the episode.

But the essential ingredient is the tone of voice when the taxi driver says to the policeman, or the Member of Parliament says to the construction worker, “Ay, gardash” “Hey, brother.” There is none of the sarcastic sourness or sharp bitterness or the macho competitiveness you may find in some other cultures that use similar greetings. It is soft and sweet, a communal sharing of the feeling that high or low in society, in the end we are all in the same mortal boat, we are all humans and this is how we greet each other.

What is even more extraordinary is when the same greeting is offered to an outsider. Maybe I shouldn’t be broadcasting these things. Maybe I should keep them to myself. After all, what will you do about it, anyway? Will you go there and see for yourself if I am telling the truth or will you go there and prove that I have pixie dust in my eyes?

One taxi driver who refused payment from me was particularly difficult to pay and I asked him if he had any kids, and he said two kids, so I said this money was for them, would he really refuse it? I shoved the money into his shirt pocket and without any pause for thinking, he grabbed his carved bone prayer beads and put them into my hand as I was hustling myself out the door. The memento is next to me as I write this. Genuine hospitality can be found elsewhere of course, but in my travels it happened mainly among relatively simple, uneducated folk. Azerbaijanis are highly educated, with a national literacy rate of 99 per cent (NY Times). So it’s the combination of an intellectually advanced society with the ancient code of hospitality associated with old tribal societies that makes this place unique.

The country is modernizing rapidly. One might rue the loss of the village quality of life in the city. To feel the real Azerbaijan, one must go to the villages, meet the old folks, drink their tea and listen to their stories, see their dances and hear their music, breathe in their ancient essence and take in an impression that is not just rare, but very refined. And so easily lost.

A WINDOW INTO THE SOUL

The song and dance belonging to a group of people is an important feature of their mindscape. One can read something essential about a society by listening to their music and observing their traditional dances. The dances in Azerbaijan engender a feeling akin to being airborne, and the arms held aloft feel like wings, as this peculiar joy-of-life sensation wells up from the belly, through the chest and into the head. There is a gentle version and a vigorous version, a scale of yin-yang in movement. It is almost impossible not to smile – but not grin – and to nearly close ones eyes, nearing a trance-like state during the gentle phase, and feeling that develop as the movements segue from yin to yang, until there is the fast and energetic exercising of one’s disciplined vigour, a crescendo of exuberance sustained and maintained.

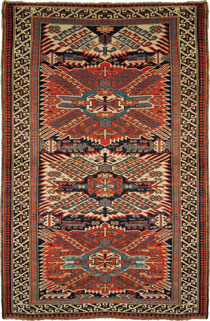

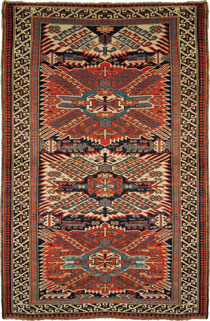

All the Caucasian countries have this traditional dance, and the Azerbaijanis have their version too. In addition, the Azerbaijanis have their enchanting folk tunes, and their transcendent mugham. If a people’s music and dance is a window into their soul then the soul of Azerbaijan must be aloft, soaring, like the fl ight of an eagle. One of the great carpet production centres of Azerbaijan is in the district called Quba, specifi - cally the village of Zeywa, whose carpets bear the image of an eagle depicted in semi abstract outline, feathers, claws, and an energetic centre that imparts the sense of a bird in flight.

The colours vibrate and the serrations do too, each on their own frequencies, a chorus of warmth and beauty. Whoever wove these fi ne abstract depictions of real life, patiently rendered in naturally dyed wool, must certainly have had that inner warmth and beauty, and the only question is which came fi rst, the carpets and their lovely, enchanting, intriguing designs, or the music they hummed and sang while they wove them.

The colours vibrate and the serrations do too, each on their own frequencies, a chorus of warmth and beauty. Whoever wove these fi ne abstract depictions of real life, patiently rendered in naturally dyed wool, must certainly have had that inner warmth and beauty, and the only question is which came fi rst, the carpets and their lovely, enchanting, intriguing designs, or the music they hummed and sang while they wove them.

Either way, together they embody the unique world of the folkloric fountainhead of Azerbaijani artistic creativity. Attuned to something in the human spirit that may very well be exactly that force in human life that Carl Jung referred to as the collective unconscious, the abstract energetic forms of the carpets and the delicate tracery of the embellished melodic expositions of mugham are manifestations of one mind, one gestalt of folkloric artistic creativity.

COMMUNAL ART

But these forms did not appear overnight, and they did not appear in one individual and then get copied by others. They evolved over time in a tribal society, expressed by individual members of that society, but belonging to the society as a whole. This notion of communal attribution of artistic creativity is strange to us westerners who are accustomed to artists signing their works and laying claim to the idea that begat such an artistic expression.

Our (western) sense of individualism, especially as it applies to the arts, doesn’t help us much to grasp the depth and meaning of the communal artistry originating with a particular ethnic group. Even this group creativity exists in a larger context of many neighbouring groups. The artistic creativity of Azerbaijani artists cannot be isolated from that of their Turkish, Turkic and Persian neighbours, each with their own signature form of artistic creativity in both musical and woven expressions. The general geographical region is crisscrossed with multi-cultural in- fl uences that are linked in a certain commonality but with vividly distinct features unique to each local region. Azerbaijan seems to me to be outstanding in certain respects. Because it is part of the Caucasus, it enjoys the cultural uniqueness of that region and that is refl ected in their version of the more general art culture shared by all the surrounding nation states with all the ethnic diversity they offer.

SONGS OF THE AGES

One tradition in the Caucasus, mainly in Azerbaijan, is the bardic tradition known as Ashiq, sometimes Ashokh or Ashug. There is no consensus on how old this tradition is. I have heard estimates that hark back over 4000 years. Talk about venerable. And durable. Ashiqlar (plural) tell the stories of legend, singing and accompanying themselves on the ancient string instrument, saz, which looks like an elongated mandolin. With three sets of three thin metal strings, the saz has a simple, sweet sound that does not tire the ears. Telling epic legends in a declamatory style of speech, the Ashiqlar keep us connected to their remote past. The sweet melodies and distinctive rhythmic patterns of Ashiq music have a story-like quality that blend nicely with the stories they tell and sing. The voice of the Ashiq is strong, powerful, electrifying, with a distinctive mountain ‘yodel’ that does not resemble the Swiss or Appalachian yodel at all but is unique to the Caucasus. I use the word yodel only because a similar group of throat muscles perform a similar fluttering glottal percussion, but the resemblance ends there. Better to just listen to some Ashiq singing, descriptions fail.

It may be the musical tradition of the Azerbaijani Ashiq that makes Azerbaijani mugham so distinctive among the many similar musical traditions of surrounding nations and ethnic groupings. And together, the two musical traditions may be why Azerbaijani carpets are so uniquely powerful and energetic in their designs and colours of all the great carpet weaving traditions from Turkey to China.

WEAVING THEIR WORLD

WEAVING THEIR WORLD

Beside their music and dance, Azerbaijanis also put heart and soul into their carpets. Ironically, however, their carpets, among the best oriental carpets in the world, were not known as Azerbaijani carpets, but as Caucasian carpets – those woven in Kavkaz Azerbaijan – and Persian – those woven in Iranian Azerbaijan. Although there are other carpet weaving tribes in the Caucasus, the general consensus is that the vast majority of carpets woven in the Caucasus were made by Azerbaijani weavers, and perhaps half of the carpets woven in Iran were also by Azerbaijani weavers.

The accepted reason for this anomaly in properly naming carpets is that Azerbaijanis were called Turks by the Persians and Tatars by the Russians who later ruled over Kavkaz Azerbaijan. Now that Azerbaijan is an independent country and the people who live there call themselves Azerbaijani – as well as millions of Iranian citizens who also call themselves Azerbaijani, this misattribution of provenance of their carpets is beginning to change. There is an effort to correct the historical record that is gaining momentum. Already a major antique oriental carpet auction house in London with a branch in Germany is referring to many of the carpets they auction as Azerbaijani.

And what makes Azerbaijani carpets unique among all the oriental carpets has to be seen to be fully appreciated. They possess an exuberance that can be electrifying, enchanting, intriguing and mesmerizing. Bold juxtaposition of colours arrayed in astonishing geometric patterns, some relatively simple, some incredibly complex, the carpets of Azerbaijan, especially antiques from the 19th century, surprise and delight. Also inexplicably harmonious with nearly every interior décor, these classic designs can be found in nearly every home of merit, be it traditional or modern.

Not all Azerbaijani carpets are equally spectacular. Many are of ordinary quality, just like anything else in life. But those carpets that have that certain character, are museum standard. One particular style of carpet is especially intriguing. It comes from one of the small villages near the town of Quba in the north of Azerbaijan called Bijov. Also known as Alpan Bijov, these small carpets resemble the wildly imaginative abstract shapes on a Rorschach inkblot. Also sporting vertical symmetry, the designs of the Alpan Bijov must be the origin of the legend of the flying carpet.

While Persians, true Persians that is, love the curvilinear and somewhat realistic flowers in their carpet designs, Azerbaijani carpets look like they are trying to capture a lightning bolt. Some antique Persian carpets emanate a rich, shimmering luster, a transcendent beauty. Azerbaijani carpets pulsate, hum and buzz. These are the carpets of the descendents of the fire worshipping mystics of the Caucasus, a window into the soul of Azerbaijan.

But there is something about village life which imparts a quality, in combination with the unique culture that brings a clear, sharp sense of Kavkaz Azerbaijan which is very much alive even in this modern epoch. It is really a matter of degree more than kind. The people in the cities are still distinctly of Kavkaz Azerbaijani society even though they are no longer villagers who have kept alive that version of society pure and concentrated.

The arts always have a role to play in defining any society and Azerbaijan is no exception. The traditional music of Azerbaijan is enjoyed widely, even though many are now listening to Azerbaijani pop or the odd combination of folk tunes played on modern instruments set to a pounding back beat. I am curious to know if anyone has conducted surveys to measure how traditional some Azerbaijanis are in society and what kind of music they listen to. Meanwhile, one only has to attend a wedding in Baku or other city to appreciate what remains of their traditions and what has begun to give way to modern sensibilities.

I would guess that an Azerbaijani who feels part of traditional society would listen more to the old music than new music and might relate socially with another traditional Azerbaijani differently than with one who is less so. There is a cultural gap that cannot be bridged with all the politeness that even an Azerbaijani can muster. They would be relating to an Azerbaijani who has become thoroughly modernized and no longer shares the same values.

THE LORE OF WARMTH…

We have already encountered the notion that Kavkaz Azerbaijan is a society with an unusual degree of appreciation for outsiders, so much so that they will excuse a foreigner for behaviour that would be criticized in one of their own. Sometimes I can’t help but wonder if there is not some element of pity for the outsider, who may never be able to give and receive the exceptional warmth of a sincere Kavkaz Azerbaijani, manifested in the simplest of greetings. It is not the ritualized exchange famous in the Islamic world, although at first glance, if that is your prior experience, you could be excused for jumping to that conclusion.

Kavkaz Azerbaijanis, with a few exceptions in some isolated areas, are not oriented in life by Islamic scripture. The basis for their extraordinary hospitality and social grace is folkloric, not scriptural. It makes for a very informal and pleasant exchange between people of differing social strata. An amusing video clip comes to mind in which a little old Azerbaijani village lady had the gumption to confront the president of the Republic and dare to speak to him in that typical way that elder Kavkaz Azerbaijanis do that can be hysterically funny. The president was absolutely tickled by the old lady and her amusing request – help in finding a husband, preferably a rich one – in spite of the vast gulf between them. I should mention that there is a certain form for this, a recognizable syntax to the delivery that is rooted in ancient traditions. Perhaps the power of the discourse is in the formalism of its exposition. Spoken differently, it likely would not have been well received.

…AND RESPECT

…AND RESPECT Of course, if someone younger were to attempt that, there would probably be repercussions, because in Azerbaijan the superior age of a person is held in high regard, regardless of one’s position in society. The extreme difference in social position between the president and an old woman villager was momentarily trumped by her advanced age, and all the president could do, surrounded by his bodyguards and a mix of local officials and villagers, was to laugh heartily at her humorous remarks. As she went on in that particular patter, the laughter increased and the amusement spread around until there was a kind of climax, a paroxysm of delight in the episode.

But the essential ingredient is the tone of voice when the taxi driver says to the policeman, or the Member of Parliament says to the construction worker, “Ay, gardash” “Hey, brother.” There is none of the sarcastic sourness or sharp bitterness or the macho competitiveness you may find in some other cultures that use similar greetings. It is soft and sweet, a communal sharing of the feeling that high or low in society, in the end we are all in the same mortal boat, we are all humans and this is how we greet each other.

What is even more extraordinary is when the same greeting is offered to an outsider. Maybe I shouldn’t be broadcasting these things. Maybe I should keep them to myself. After all, what will you do about it, anyway? Will you go there and see for yourself if I am telling the truth or will you go there and prove that I have pixie dust in my eyes?

One taxi driver who refused payment from me was particularly difficult to pay and I asked him if he had any kids, and he said two kids, so I said this money was for them, would he really refuse it? I shoved the money into his shirt pocket and without any pause for thinking, he grabbed his carved bone prayer beads and put them into my hand as I was hustling myself out the door. The memento is next to me as I write this. Genuine hospitality can be found elsewhere of course, but in my travels it happened mainly among relatively simple, uneducated folk. Azerbaijanis are highly educated, with a national literacy rate of 99 per cent (NY Times). So it’s the combination of an intellectually advanced society with the ancient code of hospitality associated with old tribal societies that makes this place unique.

The country is modernizing rapidly. One might rue the loss of the village quality of life in the city. To feel the real Azerbaijan, one must go to the villages, meet the old folks, drink their tea and listen to their stories, see their dances and hear their music, breathe in their ancient essence and take in an impression that is not just rare, but very refined. And so easily lost.

A WINDOW INTO THE SOUL

The song and dance belonging to a group of people is an important feature of their mindscape. One can read something essential about a society by listening to their music and observing their traditional dances. The dances in Azerbaijan engender a feeling akin to being airborne, and the arms held aloft feel like wings, as this peculiar joy-of-life sensation wells up from the belly, through the chest and into the head. There is a gentle version and a vigorous version, a scale of yin-yang in movement. It is almost impossible not to smile – but not grin – and to nearly close ones eyes, nearing a trance-like state during the gentle phase, and feeling that develop as the movements segue from yin to yang, until there is the fast and energetic exercising of one’s disciplined vigour, a crescendo of exuberance sustained and maintained.

All the Caucasian countries have this traditional dance, and the Azerbaijanis have their version too. In addition, the Azerbaijanis have their enchanting folk tunes, and their transcendent mugham. If a people’s music and dance is a window into their soul then the soul of Azerbaijan must be aloft, soaring, like the fl ight of an eagle. One of the great carpet production centres of Azerbaijan is in the district called Quba, specifi - cally the village of Zeywa, whose carpets bear the image of an eagle depicted in semi abstract outline, feathers, claws, and an energetic centre that imparts the sense of a bird in flight.

The colours vibrate and the serrations do too, each on their own frequencies, a chorus of warmth and beauty. Whoever wove these fi ne abstract depictions of real life, patiently rendered in naturally dyed wool, must certainly have had that inner warmth and beauty, and the only question is which came fi rst, the carpets and their lovely, enchanting, intriguing designs, or the music they hummed and sang while they wove them.

The colours vibrate and the serrations do too, each on their own frequencies, a chorus of warmth and beauty. Whoever wove these fi ne abstract depictions of real life, patiently rendered in naturally dyed wool, must certainly have had that inner warmth and beauty, and the only question is which came fi rst, the carpets and their lovely, enchanting, intriguing designs, or the music they hummed and sang while they wove them.Either way, together they embody the unique world of the folkloric fountainhead of Azerbaijani artistic creativity. Attuned to something in the human spirit that may very well be exactly that force in human life that Carl Jung referred to as the collective unconscious, the abstract energetic forms of the carpets and the delicate tracery of the embellished melodic expositions of mugham are manifestations of one mind, one gestalt of folkloric artistic creativity.

COMMUNAL ART

But these forms did not appear overnight, and they did not appear in one individual and then get copied by others. They evolved over time in a tribal society, expressed by individual members of that society, but belonging to the society as a whole. This notion of communal attribution of artistic creativity is strange to us westerners who are accustomed to artists signing their works and laying claim to the idea that begat such an artistic expression.

Our (western) sense of individualism, especially as it applies to the arts, doesn’t help us much to grasp the depth and meaning of the communal artistry originating with a particular ethnic group. Even this group creativity exists in a larger context of many neighbouring groups. The artistic creativity of Azerbaijani artists cannot be isolated from that of their Turkish, Turkic and Persian neighbours, each with their own signature form of artistic creativity in both musical and woven expressions. The general geographical region is crisscrossed with multi-cultural in- fl uences that are linked in a certain commonality but with vividly distinct features unique to each local region. Azerbaijan seems to me to be outstanding in certain respects. Because it is part of the Caucasus, it enjoys the cultural uniqueness of that region and that is refl ected in their version of the more general art culture shared by all the surrounding nation states with all the ethnic diversity they offer.

SONGS OF THE AGES

One tradition in the Caucasus, mainly in Azerbaijan, is the bardic tradition known as Ashiq, sometimes Ashokh or Ashug. There is no consensus on how old this tradition is. I have heard estimates that hark back over 4000 years. Talk about venerable. And durable. Ashiqlar (plural) tell the stories of legend, singing and accompanying themselves on the ancient string instrument, saz, which looks like an elongated mandolin. With three sets of three thin metal strings, the saz has a simple, sweet sound that does not tire the ears. Telling epic legends in a declamatory style of speech, the Ashiqlar keep us connected to their remote past. The sweet melodies and distinctive rhythmic patterns of Ashiq music have a story-like quality that blend nicely with the stories they tell and sing. The voice of the Ashiq is strong, powerful, electrifying, with a distinctive mountain ‘yodel’ that does not resemble the Swiss or Appalachian yodel at all but is unique to the Caucasus. I use the word yodel only because a similar group of throat muscles perform a similar fluttering glottal percussion, but the resemblance ends there. Better to just listen to some Ashiq singing, descriptions fail.

It may be the musical tradition of the Azerbaijani Ashiq that makes Azerbaijani mugham so distinctive among the many similar musical traditions of surrounding nations and ethnic groupings. And together, the two musical traditions may be why Azerbaijani carpets are so uniquely powerful and energetic in their designs and colours of all the great carpet weaving traditions from Turkey to China.

WEAVING THEIR WORLD

WEAVING THEIR WORLD Beside their music and dance, Azerbaijanis also put heart and soul into their carpets. Ironically, however, their carpets, among the best oriental carpets in the world, were not known as Azerbaijani carpets, but as Caucasian carpets – those woven in Kavkaz Azerbaijan – and Persian – those woven in Iranian Azerbaijan. Although there are other carpet weaving tribes in the Caucasus, the general consensus is that the vast majority of carpets woven in the Caucasus were made by Azerbaijani weavers, and perhaps half of the carpets woven in Iran were also by Azerbaijani weavers.

The accepted reason for this anomaly in properly naming carpets is that Azerbaijanis were called Turks by the Persians and Tatars by the Russians who later ruled over Kavkaz Azerbaijan. Now that Azerbaijan is an independent country and the people who live there call themselves Azerbaijani – as well as millions of Iranian citizens who also call themselves Azerbaijani, this misattribution of provenance of their carpets is beginning to change. There is an effort to correct the historical record that is gaining momentum. Already a major antique oriental carpet auction house in London with a branch in Germany is referring to many of the carpets they auction as Azerbaijani.

And what makes Azerbaijani carpets unique among all the oriental carpets has to be seen to be fully appreciated. They possess an exuberance that can be electrifying, enchanting, intriguing and mesmerizing. Bold juxtaposition of colours arrayed in astonishing geometric patterns, some relatively simple, some incredibly complex, the carpets of Azerbaijan, especially antiques from the 19th century, surprise and delight. Also inexplicably harmonious with nearly every interior décor, these classic designs can be found in nearly every home of merit, be it traditional or modern.

Not all Azerbaijani carpets are equally spectacular. Many are of ordinary quality, just like anything else in life. But those carpets that have that certain character, are museum standard. One particular style of carpet is especially intriguing. It comes from one of the small villages near the town of Quba in the north of Azerbaijan called Bijov. Also known as Alpan Bijov, these small carpets resemble the wildly imaginative abstract shapes on a Rorschach inkblot. Also sporting vertical symmetry, the designs of the Alpan Bijov must be the origin of the legend of the flying carpet.

While Persians, true Persians that is, love the curvilinear and somewhat realistic flowers in their carpet designs, Azerbaijani carpets look like they are trying to capture a lightning bolt. Some antique Persian carpets emanate a rich, shimmering luster, a transcendent beauty. Azerbaijani carpets pulsate, hum and buzz. These are the carpets of the descendents of the fire worshipping mystics of the Caucasus, a window into the soul of Azerbaijan.