It is a great feeling to stand before a Tahir Salahov painting and take in the expressive power of a truly great artist. It had long been an ambition to meet the source of that power but, given his status and the many demands on his time, it had always seemed unrealisable. However, this is Azerbaijan, where there always seems to be a way. Thus at the end of March we found ourselves in a three-floor studio/gallery that we never imagined existed in the alleys of Icheri Sheher, Baku’s medieval inner city. The paintings were impressive enough, but the man was a revelation. Skim his credentials, what images are conjured up?

It is a great feeling to stand before a Tahir Salahov painting and take in the expressive power of a truly great artist. It had long been an ambition to meet the source of that power but, given his status and the many demands on his time, it had always seemed unrealisable. However, this is Azerbaijan, where there always seems to be a way. Thus at the end of March we found ourselves in a three-floor studio/gallery that we never imagined existed in the alleys of Icheri Sheher, Baku’s medieval inner city. The paintings were impressive enough, but the man was a revelation. Skim his credentials, what images are conjured up?He is Vice-President of the Russian Academy of Arts, Hero of Socialist Labour, People’s Artist of the USSR, Azerbaijan and Russia, holder of the Heydar Aliyev and Istiglal (Independence) Awards (Azerbaijan) and Order of Merit for the Fatherland, II and III class (Russia). He was First Secretary of the Union of Artists of the USSR.

He is very obviously a man of considerable social, cultural and political standing, but far more impressive than all those titles is the simple fact that here is a man in love with life and people who can’t help expressing his feelings – whether in paint or in joyfully welcoming guests interested in his art. This character has been formed during a life lived through all the vicissitudes of the Soviet experience and beyond.

I’m going to bed, paint Chapayev

He was born in Baku in 1928, into a family which had no history of artistic leanings; his father was first secretary of the Communist Party in Lachin from 1930-37. However, there were early influences. The young Tahir was struck by pictures which had been left in their house by the previous owners. He still distinctly remembers a picture of a beautiful woman with flowing hair and hands tied behind her; he wondered how it was made. But the most direct trigger of his artistic potential was possibly a tired father’s ruse to get some peace and quiet from his three sons.

Arriving home in the evening Teymur Salahov liked to take a short rest. Putting one rouble into a silver inkpot on the table and handing out pens and paper, he would leave the room with, ‘I’m going to bed, paint Chapayev.’ A couple of hours later he would re-emerge and judge whether Sabir, Mahir or Tahir had achieved the best likeness of the Red Army hero and deserved the rouble. The oldest brother was to become a poster maker, Mahir worked on calligraphy in a cinema studio, and the youngest…. well, look at the paintings accompanying this article.

In fact a creatively weary father was not the only artistic encouragement that the young Tahir received. While at primary school he joined the Belinsky Library in the centre of the city, where an elderly librarian was in the habit of instructing young borrowers to first read, then paint a picture; the results were put on display. Again, Tahir was not the only one to benefit from this attention; Viktor Golyavkin and Toghrul Narimanbeyov (see http://www.visions.az/art,182/) also went on to become celebrated artists. He still values the simple encouragements that proved to be so effective.

The knock on the door

The nine year old boy was, however, to receive the hardest of knocks in 1937, the notorious onset of Stalin’s repression. A knock on the door late on 29 September signalled the end of normal life. Father Teymur was led away to an NKVD (predecessor of the KGB) prison and mother Sona and her five children were condemned to isolation as the family of an ‘Enemy of the People’ – friends and relations were too scared to be seen in their company. Told that Teymur had been sentenced to 10 years in prison, the family waited in vain for his release. Not until 1955 did they learn that he had been shot some 10 months after his arrest.

Sona somehow ushered her children through poverty and stigma, they all resisted adversity and achieved professional status. After school Tahir enrolled first at the Azim Azimzade State Art College in 1944, moonlighting as a poster painter for entertainments at Kirov Park up on the hill overlooking the city. The ‘posters’ were actually painted on the asphalt streets at some 20 sites around the city. As this had to be done at night, by torchlight, and there was a 12-6am wartime curfew in operation, the 16 year old had a special pass to be out. He remembers the police being diverted by his work, sometimes helping and then calling him to share their canned wartime rations. A critic was later to hail him as the artist who Began from the Asphalt.

There was no art academy in Baku then and so Tahir entered the Surikov Moscow Art Institute in 1951. The approved style in Soviet art was Socialist Realism whose mandate was the production of real, not fanciful, imagined or symbolic, images. The added proviso was that as all was advancing so well in the USSR, then artistic images should naturally reflect that good life.

Severe Style

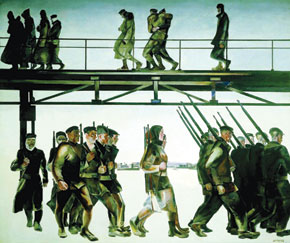

Tahir Salahov was content to work with realism, but he could not present a false optimism. His final diploma work was an early sign of what came to be known as Severe Style and is a fine example of the differences pioneered by Salahov and others in seeking to portray reality. The Shift is Over was exhibited in Moscow in 1957 and received wide acclaim, even though it almost literally did a U-turn, albeit within a Soviet tradition. A comparison with a predecessor is interesting. There are certain structural similarities between The Shift is Over and Aleksandr Deineka’s The Defence of Petrograd, but there are also crucial differences. Exhibited in 1928 in celebration of a decade of the Red Army, Deineka’s painting still reflects with a certain realism the pride in the initial struggle against the odds to establish a revolution; thus we see the suffering (above) as well as the heroic discipline of the army (below). However, with Stalin’s elimination of the collective leadership and consolidation of his own power, the struggle was over and all that was left, according to party ideology, was to celebrate the glorious achievements of the state of the heroic worker, and so Socialist Realism was the way for a generation.

By the 1950s a new tide of artists had become frustrated by this bland and blind optimism – but they were also the successors to a tradition. Rather than the heroics of the Red Army, Salahov turned for inspiration to the industrial army, especially the oil workers of his homeland.

I had lived for some time in Sabunchi on the Absheron peninsula, and pools of oil and the smell of kerosene were very familiar!

It was a summer trip to the miraculous offshore ‘city’ of Oil Rocks (see http://www.visions.az/oil,47/) that engendered The Shift is Over. In this painting, the workers are walking in similar ragged file, but in the opposite direction to Deineka’s refugees, and their demeanour is not one of defeat. They are moving in the same direction as Deineka’s Red Army but they are by no means in parade formation – this is no show, there is a real struggle going on, in this case with the elements, and it is being conducted by distinct individuals rather than a military machine. It is little wonder that their spirit and the energy in the painting, whether of the waves, the birds, the people, even the sky, brought acclaim from reviewers long subject to the monolithic mythology of Socialist Realism.

Of course, change is never easy and for some years Salahov had to overcome criticism from diehards that his paintings were pessimistic. But for those with eyes to see, there was always a heartbeat in the images – even in an industrial landscape.

Red is the colour?

Morning Train, exhibited one year after The Shift is Over, is perhaps closer to Deineka’s tradition in its presentation of ‘slabs’ of colour. There are the merest shadows of human figures and just a hint of nature, otherwise all is man-made modernity. Is there one interpretation of this painting? Do you see featureless slabs of concrete and environmental pollution, or are you more impressed by the clean, open road to progress (with the promise of trees in the distance)? Passing overhead is the fuel of this vision – oil in tanks being pulled by a train. Generally the colours are subdued except for one tank painted red and the tanks are not as clean-cut as the highway below. Salahov himself resists the suggestion that the red contrast featured in many of his paintings is any kind of trademark;

It is not deliberate; when I see red is needed, I put it in, for emotional or colour balance…

but it does make a significant appearance in a remarkable number of paintings. Does the red simply balance the colour composition? Is it a heartbeat, representing the people whose work creates this landscape? The exhaust from the train and truck, the position of the vehicles, disappearing engine and even the subtle shades in the concrete slabs, as well as the brow of the rise from under the bridge, all anticipate movement ie a human presence, even though people are almost invisible. Plenty of food for thought in a painting beautifully balanced on the lip of modernity.

Art across the curtain

As the post-Stalin thaw melted more of the frozen ideology, there was greater acceptance of new approaches, including the Severe Style and in 1973 Tahir Salahov was elected First Secretary of the Union of Artists of the USSR, a post he was to hold for nearly 20 years (1973-92). This meant a move to Moscow and the opening up of new worlds of art. This son of an ‘Enemy of the People’ had once forbidden to travel abroad (he went instead to Oil Rocks, a blessing in disguise) but it was clear from the photographs covering a studio wall that as First Secretary he had set out to meet the world and its people. From Pope John Paul to Michael Jackson, Robert de Niro and Nassia Kinski, Robert Rauschenberg and Francis Bacon, Robert, Brezhnev, Yeltsin, Putin… Not content with taking Soviet art to the West, he also brought the West to the East, organising exhibitions in Moscow with works by Bacon, Giorgio Morandi, Jean Tinguely and Jannis Kounellis. The 1989 exhibition he organised of Robert Rauschenberg’s work was the first solo exhibition by a modern American artist in the USSR and was hailed as a hugely significant symbol of the reforms underway in the Soviet Union. In the same year Muscovites saw the Lenz Schoenberg collection of European artists. There were exhibitions of Arab and Israeli artists:

It was very difficult to organise these exhibitions in the USSR, but they got a great response. For me this was very positive work. I wanted reform and to stay friendly with the rest of the world.

Portraits, the fax

As he moved in different circles, so Tahir Salahov made new acquaintances, especially among creative people and found a new challenge in conveying their characters through portraits. Given their status and the demands made of them, this was usually no easy process. He described the painting of one of his most striking portraits, that of the great cellist and composer Mstislav Rostropovich:

He was in France for a concert celebrating the bicentenary of the Institut de France, in 1995. I and my wife attended and I did a sketch on the concert programme. Three years later we met in Baku as Rostropovich was giving master classes at the Music Academy; I did some more sketching in a notebook and asked if I could paint his portrait. He said, ‘I’ll expect you at 7.15 in the morning.’ At 7.00 I was at the government place in Ganjlik where he was staying, but the security people would not let me in until 7.30.

‘You are late!’

‘They wouldn’t let me in.’

‘That’s not my concern!’

He changed out of his dressing gown into a conductor’s outfit and began playing a piece by Shostakovich; I worked on the portrait. After thirty minutes he stopped and went out to look for something; I knew he would not play again. After half an hour he was still looking:

‘What’s the matter?’

‘Jacques Chirac sent me a fax and I need to show it to (President) Heydar Aliyev at 11.00.’

The cleaner had cleared it away and it was found only after a two-hour search. Rostropovich changed and went to see the president. He returned an hour later and we all left for the airport. He asked me if I had finished. I showed him and he signed it with ‘Thank you for your talent’.

In the portrait the maestro is looking up as he plays. According to his portrayer this was a characteristic stance in his search for energy from above - the red shades in the final painting indicating just how much was required.

We were allowed a preview of another portrait in progress – eight or nine sketches in very different stances and styles – and while Tahir Salahov has a distinctive touch, he is by no means tied to one genre.

It depends on mood….on the personality…. and you think how to convey the character… Shostakovich was difficult.

Indeed, the composer’s portrait has a very different feel from the cellist’s. Shostakovich was near the end of a productive but difficult life lived through traumatic times, including periods in which political denunciations and Stalin’s disfavour threatened his life. Thus Salahov’s portrait shows a man with the weight of the world on his shoulders. This in itself brought criticism; the composer was now a rehabilitated hero and should have been depicted as such. Only as the mental shackles began to loosen, could the painting be assessed for the realism of its representation of Shostakovich’s life. And tired as he is, the composer still sits and holds onto his red-cushioned piano stool; music the heart of his life.

Carpets, curtains and cosmonauts

Tahir Salahov himself has lived a long and still very productive life. With carpet maker Taryer Bashirov he has been ‘painting’ on this most traditional of Azerbaijan’s art forms. Asked why he turned in this direction, his answer is cheerfully simple,

It’s easy to take them to exhibitions… just roll them up….

We come to sketches of designs for a production of Fikret Amirov’s 1001 Nights at Moscow’s Kremlin Theatre and he delights in telling of the way the forty thieves emerged from their urns and abseil down onto the stage. We pass the painting displayed the day Gagarin flew and used as the motif for an exhibition in Vienna celebrating 50 years of space flight.

With longer-term plans to open up his studio, it is evident that his belief in artistic communication is at the heart of an optimism and openness that has seen Salahov through the extremes of human experience: If there were no painters or writers the world could not advance. When I see good works I am happy. I have never seen a painter get up and do bad work. Every artist paints what is in his heart. Painters are the most courageous of cultural workers. They sit, work and show. If their work is not liked they take it back. I respect all artists, they work hard, whether they are Rauschenberg or a painter in Montmartre I respect them all. Tahir Salahov is undoubtedly one of the great painters of the modern era, but he is much more than even that, we hope this article gives some indication of the contribution he has made. We left our interviews with him enthused by his creativity, optimism and love for life. It takes someone special to live the experiences he has and still to give with a smile. Tahir Salahov is a very special man.