Pages 92-97

Pages 92-97By Atakhan A.Pashayev

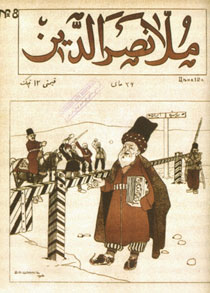

The Molla Nasreddin magazine was one of the most remarkable projects in the history of the Azerbaijani press; it represented a new stage in the development of national consciousness through art and literature, the first swallow of a glorious summer of political satire in the region in the early 20th century.

From its very inception, the magazine was involved in the fiercest struggle with the old world, in the process attracting a huge following, not only in the South Caucasus and Russia, but across the Near and Middle East. It fought on many fronts, against: the colonialism of imperialist countries and tsarist autocracy. In the East – especially with the despotic regimes ruling in Iran and Turkey – it resolutely exposed the remnants of medieval feudalism, bourgeois exploitation, backwardness, obscurantism, indolence, religious fanaticism and the hypocrisy of its ministers.

The founder, publisher and chief editor of Molla Nasreddin was the great writer, selfless journalist and public figure, Jalil Mammadguluzadeh.

Mammadguluzadeh was born in 1866 in what is now the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhchivan, entered first an ecclesiastical school and went on to the Nakhchivan city school aged thirteen where he learned Russian. In 1882, he entered the Transcaucasia teachers’ seminary in the Georgian city of Gori; this was to prove highly significant to the development of his world outlook.

Teacher, lawyer, writer, editor

Mammadguluzadeh completed his education in 1887 began work as a teacher in a village school in Irevan province. In 1901, he went to Irevan city and turned to law, studying to qualify as an advocate. In December 1903 he took his wife to Tiflis (now Tbilisi – ed.) for medical treatment, but she died soon afterwards. Here the writer Muhammad agha Shakhtakhtinski read his story The Post Box and advised him to cooperate with the newspaper Eastern Russian, published then in Tiflis, the only newspaper written in Azerbaijani. He took the advice and later became its temporary editor.

Work in the editorial office provided a great schooling in journalism for the future editor of Molla Nasreddin. Mammadguluzadeh wrote:

...the Eastern Russian was a doubly valuable experience:

Firstly, our respected writer Muhammad agha Shakhtakhtinski introduced me to the world of newspapers by taking me on to his newspaper.

The second benefit was that I met there a man whose friendship helped me to establish the Molla Nasreddin magazine.

This man was Omar Faig Nemanzade, who was to become a close friend and colleague and later an eminent journalist and public figure. Eastern Russian did not last long: launched in March 1903, it ceased publication in January 1905.

On 10 February of the same year, Mammadguluzadeh bought the newspaper’s printing-house under the pretext of fulfilling various orders.

The idea of publishing an Azerbaijani language newspaper was not forgotten, but it was very difficult to get permission to start a newspaper at that time. On 20 February, Mammadguluzadeh asked for the Tiflis governor’s consent to publish and distribute the telegrams of the Russian and Petersburg telegraph agency in Azerbaijani; permission was given on March 7. He wrote in his memoirs:

During 1905 we only took special orders at the printing-house and for a short period printed and distributed the telegrams.

Publishing telegraph news was never going to be enough for the writer of such peerless works as The Post Box and Stories from Danabash Village. His memoirs confirm this:

I wanted to write! I wanted to write so much! But I did not know why to write and for whom!? And I was not sure that the government would let me publish and distribute the things I would write.

On 10 May 1905, Mammadguluzadeh asked for the Caucasus governor’s permission to publish a newspaper called Novruz in Azerbaijani. His memoirs record:

Therefore we requested the government’s consent to publish newspapers for writers who wished to publicize their concerns. However, the three-hundred-year-long despotism of the Romanov government was still very strong. It was so strong that even in a century when the world was beginning to shake, they hesitated so much that it all ended very badly.

Second thoughts

In summer 1905 consent to publish Novruz was given. But on 11 August, he relinquished this right on the pretext of a concession to publish the Igbal newspaper owned by M.M. Vakilov. The real reason for this move was somewhat different. When the appeal for permission to publish Molla Nasreddin went in, Mammadguluzadeh wrote only that the Novruz project had been dropped for ‘certain reasons’, but he expanded on this later:

We also understood that, even if we got permission, we would be forced either to fawn upon the clergy so that the mollas would subscribe to our newspaper ….. or to write odes to his majesty the governor in our first issue in order to appear respectable to the government, as the owner of ‘Mazhar’, Kamal effendi did. But we cannot do that.

Mammadguluzadeh understood that he would not be able to show his sorrow and publicise it or popularize progressive ideas in a newspaper like that. Thus he abandoned the idea of publishing Novruz.

The great writer was looking much further ahead. Having bought the printing-house he had the means to publish a newspaper or magazine as a tool in the struggle against the autocratic regime. Of course, even in a magazine it was impossible to write everything openly but he found soon found a solution. He knew that people always expressed their most secret thoughts via the medium of traditional wise men like Molla Nasreddin and Bahluli-Dananda. When it was unwise to name the author of an article, then it was attributed to Molla Nasreddin, Hop-hop (Hoopoe), Laglagi (Joker), Hardemxeyal (Frivolous) or various other noms de plume.

The idea of setting up Molla Nasreddin was in incubation from the closure of the Eastern Russian until the magazine finally appeared in April 1906. There is no doubt that the first Russian revolution which began in 1905 was a significant factor in the magazine’s establishment.

Such a ridiculous time....

With this publication, Mammadguluzadeh opened a new chapter in the history of Azerbaijani literature and press – the chapter heading is Molla Nasreddin. As Professor Aziz Sharif wrote:

There was no great political or social event that the magazine did not respond to, and there was no matter of public interest that it would not lighten with an advanced, progressive, and revolutionary point of view.

The magazine employed sharp satire to unmask the colonial governors serving the despotic imperialism of Iran and Turkey, whose bourgeois-feudal rule exploited the people outrageously. Extorting khans, beys and feudal lords, the superstitious, merciless confessors – none were spared the magazine’s barbed wit. Mammadguluzadeh wrote:

Wasn’t it natural to establish Molla Nasreddin at such a ridiculous time, to write the history of these strange and terrible people, to describe their moods and behaviour? The Molla Nasreddin magazine was created by the nature of contemporary life itself.

Assembled intelligentsia

The newly established magazine soon assembled the most advanced team of Azerbaijani intelligentsia. Alongside the editor, Mirza Alakbar Sabir, Abdurrahimbay Hagverdiyev, Ali Nazmi, Aligulu Gamkusar, Mammad Said Ordubadi, Omar Faig Nemanzadeh, Salman Mumtaz and other similarly celebrated writers and poets were published on the magazine’s pages under various pseudonyms and cryptonyms. Pictures and caricatures were supplied by the artists Oskar Schmerling and Josif Rotter.

Mammadguluzadeh was keen to stress that the magazine was not the work of a single man, it was the product of several close colleagues and he himself was just their ‘leading friend’. However it was produced, it achieved great popularity, not only in the South Caucasus and Russia, but across countries of the Near and Middle East as well. It was distributed widely in Iran and Turkey. The tsarist government suspected that the magazine was connected to revolutionaries in Transcaucasia and Iran and kept it under close scrutiny.

In its early days the magazine was banned by Iran and Turkey. In a satirical article, Potbellied, published in issue No 36, 6 December 1906, Mammadguluzadeh wrote:

We decided to increase our readership a little by distributing calendars and booklets; but that goddamn devil; everyday he comes to us and insists, for example, that we write that in Tabriz the successor to the throne assembles his ‘humble’ robbers and sends them to ransack Iran’s villages and cities and distributes part of the booty between them, keeping the rest for himself.

If we wrote such things in our periodical, as soon as the successor, Mahammadali Mirza, read it, he would order them to burn it at the border...

Then we read in a story:

The Ottoman consulate sends an order to our office: “If you once more write bad things about Sultan Hamid, i.e. if you write once more that when the Ottoman Minister of Foreign Affairs informed the sultan that European governments were preparing to give Crete to the king of Greece, Sultan Abdulhamid summoned his Greek harem and said: ‘I would give up Crete, Damascus and Bosnia before my Greek wife’s black mole’, I will write to Istanbul and ask them not to allow Molla Nasreddin onto Ottoman soil.”

Nevertheless, Molla Nasreddin continued to publish sharp cartoons and comment on events in Turkey and Iran and there were repeated representations to the governing tsar requiring that the magazine refrain from satirising the sultans of Iran and Turkey.

Sultan insulted

The magazine was closed down in 1907 and until recently the main reason was believed to have been an article about Akhund Pisnamazzada, the Sheikh-ul-Islam (religious head of Shia Muslims) of Transcaucasia and two open letters written by Mammadguluzadeh in issue No. 22 of the magazine on June 2 of that year. The satirical articles in that issue gave an extensive airing to the topic of women’s freedom.

But newly-discovered documents reveal the real reason for the closure in 1907. In March of that year, Feyzi bey, Turkey’s consul general in Tiflis, went in person to see L.S.Kokhanovski, an official in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs representation to the Caucasus governor, taking with him issues 23 and 29 of 1906 and 1 and 11 of 1907; all of them carried sharp caricatures of the Ottoman sultan. ‘In the context of the friendly relations between the governments of Turkey and Russia’ the consul offered to deliver to the governor of the Caucasus a request that he take appropriate measures to prevent the publication of articles about the sultan and government of Turkey in the magazine. The governor, after making some enquiries, in his turn ordered the governor-general of Tiflis to take the appropriate measures. The governor summoned Mammadguluzadeh and ordered him to:

stop publishing caricatures of Turkey and the sultan of Turkey.

From early April until late May nothing was published in the magazine about Turkey. But in issue 21 published on 26 May, the magazine again published a cartoon criticizing the plunder of the Turkish people’s wealth. The new documents prove that the real reason for closing Molla Nasreddin in 1907 was not the raising of women’s freedom, but the publication of cartoons about Turkey.

…the cause of the steps taken regarding the magazine is publication of a critical article directed against the leaders of neighbouring Muslim countries and articles which are inappropriate from the diplomatic point of view.

The magazine was to return to this episode several years later. Influenced by the first, 1905-1907 Russian revolution and the revolutionary movement in Iran, the Young Turks also sprang into revolutionary action. In April 1909, Sultan Abdulhamid II was dethroned. Mehmed V, who swore to be faithful to the constitution, was elected by the parliament to be the new sultan of Turkey, but the Young Turks were unable to resolve the main problems of the bourgeois revolution in Turkey. The country remained a semi-bourgeois, semi-feudal state. The Ottoman Empire gradually collapsed as the movement for freedom strengthened and Molla Nasreddin could not ignore these events. Thus on 31 December 1911, issue 47 had an article Abdulhamid:

This is the same Abdulhamid whose picture in our publication was the cause for complaint by consul Feyzi bey to the Russian government. It is now clear that while there have been so many rulers, shahs and sultans in the world, not one has been so bad an enemy to his nation and the state.

Parliament consulted

It is a fact that a meeting of the Iranian parliament was dedicated to a discussion about an article published in Molla Nasreddin. On 21 August 1910, one of the Russian embassy staff in Tehran, stated in a letter to Petersburg that:

the whole meeting of the parliament was dedicated to an attempt by parliamentarian Seyid Nasrulla to clear himself of criticism for indecent behaviour in the comic magazine Molla Nasreddin, published in Tiflis.

Back by public demand

52 editions of the magazine were issued in 1908 and 1909. In 1906 there were 39 issues, in 1907 - 49, in 1910 - 42, in 1911 - 47, in 1912 - 9, in 1913 – 29 and in 1914 - 25 editions appeared. These figures reveal the effect of tsarist censorship, hindering regular publication. It is clear from archive documents that although the magazine was banned and prosecuted several times and suffered confiscations of issues among other problems, Mammadguluzadeh continued stubbornly on his way. The question arises of how the magazine continued for such a long period in such difficult conditions. The main reason was its authority within the general population and the intelligentsia and their active support. In 1907, for example, the temporary governor-general of Tiflis took the decision to close the magazine. But he had to relent due to popular demand.

The closure in 1907 coincided with Mammadguluzadeh’s marriage to Hamida khanim. The Karabakh beys were not happy about a woman from the family of a respected landowner marrying a renegade journalist who criticised the governing class and the mullahs. They tried to set up an ‘accident’ at the Aghdam bazaar for the phaeton carrying Mammadguluzadeh to Tiflis and to injure or kill him. On the other hand, Aghdam’s intelligentsia telegrammed the temporary general governor of Tiflis asking him to allow the earliest restoration of publication of Molla Nasreddin, which was:

the real teacher of Muslims, showing them the way to morality and honour.

The magazine’s circulation was one of the largest of the periodicals of that period. From a letter sent to the Tiflis Committee’s head office for press matters on 26 November 1909, we learn that while Molla Nasreddin had a circulation of 2,500, the Mazhar newspaper was printing just 200 copies.

Later information indicated even higher figures. In 1913, the Tiflis Committee’s office for press matters recorded the confiscation of 3,505 copies of the 16th edition of the magazine. It had subscribers not only in Russian, Iran and Turkey but also in America, England, France, Italy, India, China, Finland and other countries.

Libraries in Russia, Paris, Cambridge, Ankara, Istanbul, Tehran, Helsinki and other cities all hold collections of the magazine.

Molla Nasreddin did the spadework for a Muslim satirical press along the Volga, in Central Asia, Iran and Turkey. The satirical magazines Bahlul, Zanbur, Mirat, Kalniyat, Mazali, Tuti and Babayi Amir in Baku, Laklak in Irevan, Gachiga and Chokuj in Orenburg; Yashen and Yalt-yult in Kazan; Tup in Astrakhan; Azerbaijan in Tabriz; Nasimi-Shimal in Resht; Suri Israfil in Tehran; Garagoz and Khoja Nasreddin in Istanbul and others all owed something to its influence.

Molla Nasreddin continued to appear under the Soviet regime. It was published regularly in Baku from late 1922 until early 1931, before Jalil Mammadguluzade, progressive pioneer of satire, died in Baku in January 1932.

Bibliography

1. Mammadguluzadeh J., Works. p.1-6. Baku, 1983-85

2. H. Mammadguluzadeh’s memories of Mirza Jalil. Baku, 1967

3. Mammadli G., Molla Nasreddin. Baku, 1966.

4. From The History of the Publication of the Magazine Molla Nasreddin. Baku, 2009

5. Pashayev A., Molla Nasreddin: Friends and Enemies. Baku, 2010

6. Ed. V. SPb., Collection of Diplomatic Documents on Events in Persia. 1912

7. A. Bennigsen et Ch. L. Quelquejay., La Presse et le Mouvement National chez les Musulmans de Russie avant 1920. Paris, 1964

About the author: Atakhan A.Pashayev, PhD in History, is Head of the Azerbaijan Republic State Archive Department and author of research into J.Mammadguluzadeh and the Molla Nasreddin magazine.