Pages 60-63

Pages 60-63by Bakir Nabiyev

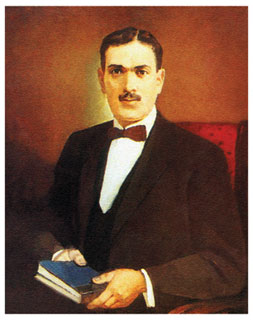

Ahmad Javad Muhammadali Akhundzadeh was born on 5 May 1892, in the Seyfali village near Shamkir, west Azerbaijan. His grandfathers were from Southern Azerbaijan.

His father Mullah Muhammadali was one of the rich intelligentsia of the time, but he died when his son was only six years old. Ahmad was soon recognised as a clever and perceptive child; even before school he knew some Suras of the Qur’an by heart and recited them in a pleasant voice.

He began his education at the Muslim school in his own village. The family went through difficult times when his father died and his mother Yaxshi khanim moved the few kilometres to Ganja and took work in a carpet workshop, putting Ahmad into the Muslim seminary near the Shah Abbas mosque for a good secondary schooling. Among his teachers were fine intellectuals such as poet and playwright Huseyn Javid, Sheyxulislam Pishnamazzaddin and others. As Ahmad excelled in difficult family circumstances, the school’s management provided him with a scholarship. He began writing at the seminary and attracted attention from teachers for his first poems.

Patriotism and love

Following Newton’s third law ‘To every action there is always an equal and opposite reaction’, as the chauvinist policy of tsarist Russia sharpened against minor nations, so Azerbaijani youth, particularly the rising educated generation, increasingly turned towards their origins and national roots; there was a growing respect for Turkism. Thus, when war broke out in the Balkans, a special Caucasus Volunteer Group, consisting mainly of Azerbaijanis, went to the battlefront on Turkey’s side. Ahmad Javad was one of the volunteers.

He had graduated that year and qualified as a teacher. During the First World War he was secretary of the Azerbaijan Charity Society which helped victims of the fighting, particularly in the Turkish cities of Erzurum and Kars, and in Georgia’s Batumi. Alongside this charitable work he found the time to write articles and poetries to inspire a national consciousness.

It was in Batumi, in 1916, that he met and fell hopelessly in love with Shukriyya khanim, a student in her last year at the girl’s gymnasium; she returned the feelings of the young, handsome and talented Azerbaijani poet. Shukriyya’s parents, Suleyman bey and Sahar khanim were members of the Batumi nobility. Although, Suleyman bey knew Javad, and had supported his charity work, he gave a negative response to the writer Ali Sabri - the petitioner sent by the poet. This, however, strengthened the young couple’s love for each other. Despite the difficulties in communicating, they somehow manged to elope… to Ganja. The poet found work as a teacher and their son Niyazi was born in1917. Shukriyya’s family were reconciled to the situation and the marriage flourished.

The October Revolution of 1917 gave patriotic Azerbaijanis the chance to throw off the Russian imperial yoke. They gathered in Tiflis (now Tbilisi) and, after much struggle and sacrifice, established the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR) on 28 May 1918.

Anthem to independence

The first capital of Azerbaijan’s first democratic state was Ganja, where Javad lived and worked. The poetry he wrote in that period shows clearly enough what this new, independent state meant to the lives and destinies of the patriotic, progressive intellectuals who had worked to achieve it. One of those poems was later adopted as the national anthem of the ADR and set to music by perhaps the country’s greatest composer, Uzeyir Hajibeyov. The ideological and artistic power of the song is such that it is also the anthem of the modern republic. It is as if the words are not written in ink but with the blood of the poet’s heart. The repeated exclamation of ‘Azerbaijan!’, ‘Azerbaijan!’ as a final chorus is a climactic summation of the text and music and around the central aim and idea. The text of the anthem, with some changes, was published in Baku in 1919 in the book National Songs and signed Jemo, representing the first letters of Javad Mammadali in the Arabic alphabet. (see and hear a version here - http://is.gd/ByGLwL)

The articles he wrote during the period of independence from 1918-20 shed some light on the poet’s biography. The article Independence Day in Ganja, dedicated to the first anniversary of the ADR, is very typical. His impressions of the holiday celebration on 28 May 1919, reveal Javad’s belief in independence as the greatest gift afforded the nation; a belief expressed in both his poetic and his political writing.

In late April 1920, the 11th Red Army, consisting mainly of Russian Bolsheviks and Armenian Dashnaks, crossed into Azerbaijan. The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, the ideal for which Javad had struggled, collapsed. Several months later he was sent to Gusar as a teacher. With his family, he moved to Khulug village of Gusar, in the country’s north-east, again working as a teacher. He was soon appointed school director.

It was here that the first seeds of the great tragedy that was to befall Ahmad Javad were sown by cruel and fickle fate. Mir Jafar Baghirov, who later became the Head of the Emergency Commission (the Cheka, forerunner of the KGB) in Azerbaijan and head of the Central Committee of the Azerbaijan Communist Party, also worked at that village. The poet read some of his works to Baghirov, they were full of the peoples’ spirit of Turkism and the latter liked them. The significance of Javad’s brief acquaintance with Baghirov to his repression and murder 16-17 years later is absolutely clear…

Denounced

In 1922, Javad entered the High Pedagogical Institute in Baku. In 1923, he was arrested. He was accused of assisting Mirzabala Muhammadzadeh a brother-in-arms of Mammad Amin Rasulzadeh, one of the driving forces behind the ADR, to go to Turkey. But, fortunately, the accusation was not proven and he was released. He went back to teaching language and literature at the Narimanov technical school. In 1924, he was elected secretary of the Literature Society. In 1925, he was appointed secretary of the journal Enlightenment and Culture. Working and studying at the same time, he graduated from the Institute and began working mainly in higher education institutions. He was a teacher at the Azerbaijan Polytechnic Institute and an associate professor at the Azerbaijan Agricultural Institute. In 1930, he moved to Ganja, with the institute, and later became head of the Department of Linguistics there, being one of the first Russian language professors in the institute.

Ahmad Javad taught at technical schools and high schools for many years, devoting his life, education and science to the nation’s youth. His deep knowledge, high culture and heart of a poet made him a popular teacher with students who maintained contact with him as they spread through the various regions of Azerbaijan.

The ideological authorities were not so happy with him, however: the Red Pens society of ‘proletarian’ poets, his adversaries, from time to time issued statements, made up false information, called him to the ‘right path’, to accept the new structure and to praise all its works, threatening that, otherwise, he woud be subjected to severe punishment. The writer A. Nazim declared in an article published in Moscow (1929) that some of Javad’s poems had been published in Istanbul in a book called For the Sake of Liberty. This news was a bombshell dropped into the tense atmosphere that already existed and the sensation had far reaching consequences.

In his poem I Strongly Protest, the poet declared that he knew nothing about the book, published after the April 1920 revolution by an organization he had no connection with, and that he had no idea about which of his works had been published in that book. His protest only stirred further the passions surrounding him and enraged opponents who waited for him to admit his ‘mistakes’.

Poison pens

Thus, the ideological chauvinists first spread the false information that Javad had sent his poetry abroad, and then began a new anti-Javad campaign.

In April 1932, the Central Committee of the All-Union Bolshevik Communist Party issued a special decision, The Reorganization of Literary and Artistic Organizations. By this decision, the Unions of Proletarian Writers were abolished and a single organization of writers ‘assisting the Soviet platform’ of the USSR was established. But locally, in the national republics, the Union of Soviet Writers had been established. The organizational committees founded there began their fieldwork. A plenary session was held in Baku in April 1933 to carry out the Central Committee decision to create the single Union of Writers. Writers were no longer to be attacked for not being original proletarians and creative intellectuals who were fellow travellers would be given the opportunity to participate in the ‘organisation of the new world’. However, the main purpose in making this decision was to stir up passions, encourage intellectuals belonging to the same nation to expose each other and thus, pave the way for the repression of 1937.

This process was particularly painful in Azerbaijan, numbers of talented writers were persecuted in this process, apart from the shattering psychological effect they were not allowed to work in any area of education or culture to maintain their families. Their past work was re-examined, ‘analyzed’ and ‘exposed’ for offences against ‘proletarian culture’. Javad was certainly one of the first targets among literary figures, judging from the number and viciousness of the attacks against him. In fact, at the plenary sessions held to discuss the establishment of the Union of Writers (1933), almost half of the discussions were dedicated to the fate of ‘old’ writers, including Javad. His works were characterised as anti-revolutionary and he was criticized strongly from all sides. He responded to the attacks with comprehensive speeches.

In 1934, a terrible tragedy struck the poet’s family. His beautiful, clever sixteen-year-old daughter Almas fell ill with a malignant tumour. Ahmad and Shukriyya khanim mobilized all their material and moral resources as well as their parental compassion. They took Almas to many physicians in Azerbaijan and Georgia, but even a professor invited from Moscow could not help her and treatment met with no success. … his daughter’s tragedy was a bitter blow. As his older son Niyazi Akhundzadeh wrote, Javad’s black hair turned grey as a result.

Javad moved to Baku in 1935 and worked as an editor of translated works at Azernashr publishers. He also worked at a cinema studio. After a gap in his poetry writing, he took up his pen once more to write a poem dedicated to the misfortune of his ill-fated daughter …

1937 – year of terror

One tragedy followed another. The attacks on scientists, literary and artistic figures in the press and at public meetings, for some reason mostly targeting Javad, increased and peaked in 1937.

At the March 1937 plenary session of The Union of Writers, his opponents were not satisfied with dwelling on the latest events and stories, they delved into the past, presenting the ordinary, everyday, facts of literary life in a political context and in very ugly form. Even expelling the poet from the Union of Writers did not sate the anti-Javad thirst. Materials about him had already reached the Union (Moscow) press, the strictures grew stronger and the demands more devilish. Always regarded with suspicion by Bolshevik and Dashnak politicians, his expulsion from the Union of Writers left him open to further attack and, on 3 June, Ahmad Javad was arrested.

He knew what awaited him from the totalitarian regime. He had a chance to escape to Turkey, but he did not want to even think about that. How could a poet who loved his children and family so much leave them to save his own skin? Pride and forbearance were essential to his character. Those closest to him said that, even in his most difficult trials, they never saw. Javad suffer, complain, or descend into deep sorrow. His view was one of optimism and benevolence. This was not just habit, it was, as someone remarked, a magical belief, the strong light of his inner humanity. Like creatures of the night, his enemies were afraid of this light and did all they could to extinguish it.

Case No 12493

It was terrifying to read about the persecution Ahmad Javad suffered under the Soviet regime: the repeated arrests, trials, oppression and torture he suffered in jail, the tragedy that befell his family, especially his wife Shukriyya khanim. I trembled to take up my pen to make notes on the information. There are terrible materials about case No 12493 in the archives of the former Peoples Commissariat on Internal Affairs (NKVD) of Azerbaijan. After decades of secrecy, comprehensive information was finally disclosed, including the content s of one case from the State Security office’s fourth devision. The necessity of instituting proceedings against A. Javad was justified as follows.

Akhundzadeh Ahmad Javad … has been a member of the Musavat (Equality) party since 1918. Within the period from 1920 to 1923 he was a member of the secret staff of the party’s Central Committee and that is why he was arrested in 1923; but he was officially released. He was one of the leaders of the ‘Green Pens’ Musavatist society … He did not leave his Musavatist position, continued his secret Musavatist activity and conducted propaganda in the spirit of Musavat among young Azerbaijani poets who gathered around him. From his anti-revolutionary Musavatist position, Ahmad Javad cast aspersions on the leaders of the republic, the party and the national policy they conducted… He participated in the activity of the anti-revolutionary, bourgeois, nationalist organization. It hardly needs saying that, according to ordinary international law accepted in civilized countries, even if everything written here were accepted, there are no serious grounds for the institution of criminal proceedings. This poet of gentle, romantic nature and strong national spirit, this translator of classical literary works from various languages and tireless publicist fell in the struggle for the freedom and independence of Azerbaijan, labelled an enemy of the people. On 3 June 1937, state agents entered Javad’s apartment and conducted a search. They seized the souvenir dagger presented to him by friends and Shukriyya khanim’s jewellery.

What does it mean, Karabakh was like heaven?

They took both of them away. (Shukriyya khanim was allowed to return home, only to be arrested again later and sent into long-term exile). As an indication of the pettiness of the poet’s accusers they asked him about the first line of his poem Leyla, written in 1934:

They say that Karabakh was like heaven

They asked him,

What did you mean by writing that? What does it mean, Karabakh was like heaven…? You wanted to say that now it is not?

Subjected to indescribable torture, during the first month and a half Javad rejected the accusations made against him and did not give false testimony against his colleagues; he flatly refused to add new names to the long black list drafted by his enemies. However, persecution, provocation, the tormenting of people with unorthodox views and the suppression of simple civil rights and freedoms had its effect.

The poet, after repeated beatings, suffering head injuries and deafness and falling into a fever eventually incriminated only himself. The torture applied in the prison of Beria, Baghirov, Gerasimov, Markaryan and Grigoryan, finally broke his strong spirit; he pleaded guilty and confessed to conducting ‘harmful activities. On 12 October 1937, the Military Board of the USSR Supreme Court imposed the death penalty, and the same night one of the most unjust death sentences in history was carried out. The executioners put an end to the life of the 45 year old poet…

Persecution continued

The tragedy of the surviving members of his family continued. 15 days after Javad was killed his wife Shukriyya khanim, who was closest to him and to whom he dedicated his rare poetic works, was declared the “wife of an enemy of the people” and was arrested together with her children. Again the state agents entered their apartment and searched it. Everything was seized. On 23 December, Shukriyya khanim and her children were deported to Akmolinsk. The children: 16 year old Aydin, 14 year old Tugay and 2 year old Yilmaz were handed over to the child reception point of the Peoples Comissariat for Internal Affairs. Tugay was sent to a camp for ‘problem children’ in Nikolayev city. Niyazi was of age and so he was also separated from his brothers. He was kept in Bayil prison for 3 months and 19 days and was released after multiple interrogations. After a short break Niyazi, realising that he was wanted, ran away. Fate took him to Leningrad. He found work there as a loader with the assistance of Azerbaijani intellectuals. In 1940, he entered the Financial and Economic Institute. He served at the front from the very beginning of the Second World War at his own request and was decorated. After demobilisation from the army he entered the Faculty of Geology at Baku University.

Shukriyya khanim, whose husband was shot and who was forcibly deprived of her children, suffered for 7 years in exile. Although she was released in 1945, she was not allowed to live in Baku. Only in December 1955 was the criminal case against the poet’s wife closed.

About the author: Professor Bakir Nabiyev is a PhD in philology, a member of the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences and Director of the Nizami Institute of Literature. He is the author of 40 books and many articles on Azerbaijani literature.