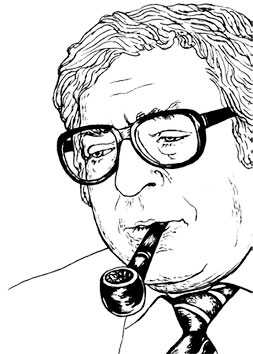

Anar (Anar Rasul Rzayev), well-known modern Azerbaijani writer, was born in 1938. His literary work dates from 1960. He achieved popularity with his very first publication - throughout the Soviet Union as well as in Azerbaijan - for his originality and the innovations in style and themes that he brought to the literary environment. White Port, Dante`s Anniversary, Contact, The Sixth Floor of the Five-storey House, Opportunity, Hotel Room etc. captured the affections of his readers. His dramatic works also attract large audiences and he is well-known as a film scri ptwriter and director.

Anar (Anar Rasul Rzayev), well-known modern Azerbaijani writer, was born in 1938. His literary work dates from 1960. He achieved popularity with his very first publication - throughout the Soviet Union as well as in Azerbaijan - for his originality and the innovations in style and themes that he brought to the literary environment. White Port, Dante`s Anniversary, Contact, The Sixth Floor of the Five-storey House, Opportunity, Hotel Room etc. captured the affections of his readers. His dramatic works also attract large audiences and he is well-known as a film scri ptwriter and director.His works have been translated into more than twenty languages. He was active in tackling the problems facing the state and the nation both during the Soviet period and the period of independence. He was a member of the Parliament of the Azerbaijan Republic.

Anar is noted for his great organizational work to support literary and artistic creativity in Azerbaijan: he has been Chairman of the Writers’ Union of Azerbaijan since 1991. We are happy to present here Anar’s The Morning after that Night (1964). (Anar, Works vol. І stories, p. 248-256. Baku, 2003). In this story the writer skilfully portrays the psychological discomfort suffered by people living under the Soviet repression of 1937.

The night in 1937.

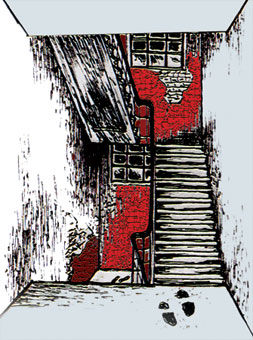

A silent street in Baku. Two big apartment blocks face each other at the opening of the street – blocks heavy as flat irons.

A small park nearby.

Just as the earth absorbs water, the street has swallowed the sounds of the day, sounds of chatter, footsteps and wheels. The park has emptied, now missing the laughter: the slats of a bench resemble the spotless, striped pages of a copybook.

On just one bench – the one a branch droops over, like a broken wing – a couple cuddle up together; the young man smoothing his girl’s hair.

Park, street and blocks have faded into the darkness. Only the faint light from one window of the four-storey block on the right leaks into the night.

All are asleep. But it is an anxious sleep. At about two o’clock in the morning, the silence of the night is split with a screech – a car has stopped in front of the four-storey block. The rusty brakes applied to the speeding car slice like a knife through the sleep of those in their apartments.

Nobody gets up. Nobody goes to the balcony. Nobody goes near a window. A husband and a wife have lived for years in flat number 1 on the ground floor of the four-storey block.

Bashir kishi* is a domkom*.

His wife’s name is Zuleykha.

Zuleykha has been dreaming about her village. Snow-white smoke rising from the flue of their hut. Someone shouting loudly:

- “You girl, Zuleykha, take these dishes and wash them up, where are you, girl?”

Zuleykha approaching, knowing who was shouting – her mother. In his dream, domkom Bashir is drinking tea. Strong tea, steaming pleasantly in an armudu* glass.

The rusty brakes wake both of them at the same time. They listen: the car doors open. Zuleykha whispers:

- “Allah, preserve us from danger!” She tries to recall and interpret the dream she has just seen. Water is happiness, her mother …

The car doors slam shut.

Zuleykha:

- “Allah, preserve us from danger!” Footsteps are heard. Bashir trying to guess the number of visitors from the sound of the steps: three or four.

The entrance door to the building opens. The steps come too close – right to Bashir’s door.

- “I wonder who has gone tonight.” – Bashir’s thought.

The footfalls pass their door.

Opposite Bashir’s door, in flat number two, lives an old widow, Zahra qari*. She has two rooms. After her husband’s death she rented one of them out.

Aunt Zahra is a little hard of hearing and fast asleep. She could sleep through gunshots. So she does not wake up this time either.

Her tenant is a typist, Sakina. Sakina is thirty two, mild-mannered, a plain face - a modest young woman.

She woke as soon as the car stopped at the door. Listened anxiously. As the footsteps approach their flat fifty two thousand thoughts go through Sakina’s mind. Her thoughts scatter like quicksilver, then return and reassemble, break again, merge once more.

- “It can’t be for just one letter. Nobody except Ahmedov knows about that. Would Ahmedov really do such a thing? No, no. It’s true that it was a very important word, I should have made a mistake with an ordinary word, that damned “z” just had to go next to the “p”. No, I don’t believe it. Ahmedov would never do such a thing. But he is only human, you never know, perhaps for fear of his own life… no, he is not a cowardly man, well, but only the two of us were in the office. Who knows? Perhaps I frightened him. To make a mistake in such a word... but who would have thought that one letter could change the meaning in such a way? Now how can I prove that I didn’t do it on purpose; that it happened by accident? Why would I have done it on purpose? I am a simple person, just doing my job, I write hundreds of pages, just one letter. Why no, Ahmedov is a true man, even though he often tells me off, he would never be mean to me. No, no it can’t be, I don’t believe, but what can I say? Why but….”

Sakina takes the handkerchief she embroidered herself from under the pillow and wi pes the cold sweat from her forehead, she hears the footsteps on the stairs.

Flat number three on the second floor is Surkhay’s. Surkhay is an unmarried architect. The faint light leaking out onto the street is filtering from his window. Surkhay is working. He has to complete and hand in a project for the building of a new school. So he is working through the night.

He is so preoccupied with the project that he is unaware of events outside. He has heard neither the screech of brakes at the entrance door nor the footsteps. Even though the steps ring out near his door he does not hear them, the sound passes. Heading towards flat number four.

Gurban kishi, who lives in flat number four is an old party member.

Every night for the last three months Gurban kishi* has put beside the bed two sets of clean underclothes, tooth-powder, a toothbrush and three bars of soap –friends have called him fastidious since his youth.

As soon as the car stopped Gurban kishi opened his eyes. He had not yet fallen asleep. He has slept badly of late. However, he is calm and relaxed. While the footsteps were climbing, step-by step, Gurban kishi was thinking:

- “So 14 April ’37.”

Some days are the most important in a person’s life – days engraved on the memory, birthday, the day of one’s first love, parenthood, the funeral of a dear one, the birth of a great hope - days engraved on the memory, one more day, a day that is not engraved on the memory, the day when memory dies, the day of death, the most important days in a person’s life.

The sound of footsteps approaches Gurban kishi’s door.

Gurban kishi repeats:

- “14 April.”

and for some reason he relives the most important days of his life.

7 December. The year 1903. The first secret student meeting.

18 August. The year 1904. The first student demonstration.

28 April. The year 1920. Baku. The morning of the revolution.

22 February. 10 September. 8 July. Tsarist exiles.

The years of revolution.

The civil war.

5 October. The last serious confrontation with somebody.

For the seven months that have passed since that day, Gurban kishi has been waiting for an important day in his life, to be more precise, an important night in his life. Waiting every night. Waiting for this night.

- “So the night of 14 April.”

Now Gurban kishi thinks not of this date, but of another date. He knows that even though this night is an important date in his life, it is not the final important date. He knows there is also an important day, an important morning in his life. The morning opening to truth, to justice. When will that morning come? What day? What year?

The footfalls pause near Gurban kishi’s door.

Gurban kishi leans onto his elbow, half rising from the bed to open the door, lowers his foot and tries to find his sli ppers. His bare foot touches the floor and he shivers; he bustles in the darkness like a blind man searching for the way with his stick and finds the sli ppers.

Gurban kishi puts his right foot into a sli pper but not his left foot, he is motionless, surprised, hearing the noise of footsteps fading slowly away.

There are two flats on the third floor.

Flat number five was emptied two weeks ago. A composer called Faraj had lived there. Nobody has moved into the flat yet.

Someone called Javanshir, his wife Tavus and their six year old daughter Rana live in flat number six.

As soon as the car turned into the side street, the hand stroking Tavus’ waist, Javanshir’s hand, fell motionless.

After a while Javanshir moved away from his wife and jumped up.

Tavus was also stressed and fell silent. They listened.

Little Rana is in a sweet sleep: there is a big, bright, blue window in her dream, a window without curtains. Somebody is teaching her to count: one, two, three, four, five.

One, two, three, four, five. One, two, three, four, five.

As soon as the car stopped and the sound of footsteps was heard, Javanshir said only one word to Tavus:

- “Gurban”.

Perhaps he had a reason for saying that. Two weeks ago when the noise of a car was heard, Javanshir had said only one word to his wife:

- “Faraj”.

When Tavus first understood, she frowned for a moment. Javanshir:

- “You are a woman, - he said - don’t meddle in man’s business”.

Two days later Tavus was happy again: - “It is none of my business - she thought – he is a man, he knows what he is doing”.

It was also reassuring to some extent. The night they made up, Javanshir kissed his wife’s neck and whispered:

- “I have not dreamed up anything, I don’t concoct, when I am asked I say that I heard it with my own ears.”

When the footsteps passed Gurban kishi’s door and hit the stairs the bed became uncomfortable. Javanshir puts his hand into the pocket of the jacket hanging near the bed, brings the cigarette to his mouth with quivering fingers.

- “Maybe they are mistaken - he thought - well, don’t they know that there are only two flats on this floor. The fifth is empty and the sixth is mine...”

- “Listen, Tavus, you haven’t talked too much, have you?”

- “What do you mean, Javanshir?” - “You know those lady friends of yours are very good at careless chatter.”

- “O Javanshir, we have talked about that and finished with it. None of them have been here since then and I have not seen their faces at all. You know better than me that we have stopped talking to all our friends and relatives. We don’t see anybody.”

The steps pass the door of the fifth flat.

- “O Javanshir,”

Tavus’s voice quavering. She cannot decide whether to tell. Finally she decides; anyway it is better for Javanshir to know.

- “You know, Javanshir, Rana, the brat, was singing that song again.”

- “What?”

Javanshir jumps out of the bed. The childless and widowed composer Faraj had loved little Rana whole-heartedly. He would teach her the funny, new children’s songs that he was composing.

The day before yesterday Javanshir was reading the newspapers and studying world events when suddenly he leaped up as if stung: Rana, unaware of world events, was lulling her doll to sleep and singing a cradle song, a song composed by enemy of the state, Faraj.

Javanshir was so taken aback that he hurled himself into the other room and, without any explanation to wife and daughter, gave Rana one, two slaps across the face. Eventually he calmed down and told Tavus that if he heard anything like that from the brat again, she alone would be to blame.

The sound of the steps stopped at Javanshir’s door.

Tavus, breathing heavily:

- “Yesterday she was singing it again. I grabbed her ear, she said that she had forgotten the song and was singing it again to find out if she had forgotten it completely or not.

In saying this, Tavus does something strange, she smiles.

A smile in this year, on this night and at this moment in this flat, is a great betrayal for Javanshir. He grasps Tavus’s arm:

- “Shut up” - he says, and swears.

The steps move away from their door.

Javanshir lights his cigarette with a nervous gesture.

- “I should have guessed, I am pigheaded - he says and laughs – I totally forgot.

You know there is one more floor upstairs.”

- “The fourth floor” – she sheds a few tears. Her husband’s swearing is still burning her ears.

- “The fourth floor” - Javanshir thinks - The fourth floor? Who will be there? The captain? The oilman?”

There are two flats on the fourth floor.

Salayev lives in flat number seven. He is the captain of a shi p travelling to Astrakhan.

Three days a week, on Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays, he is at home, and he is at sea on the other four days.

- “Today is Friday” – thinks Javanshir –

So it must be oilman Zeynalli? Imagine! Who would have thought? Such a swaggerer. He doesn’t even greet anybody these days”.

Javanshir pricks up his ears and listens.

The sound of the steps passes flat number seven and stops at the door of flat number eight. There is a knock at the door of flat number eight. It is a loud knock. The whole block hears it.

Javanshir in flat number six thinks:

- “So citizen Mura Zeynalli. So you were swaggering? And three big, light rooms have been emptied. I wonder who will move in.

You would never guess from Zeynalli’s imposing appearance that his life was going badly!”

In flat number five... The door of flat number 5 is sealed.

Gurban kishi is pacing up and down in flat number four and thinking, thinking... “Perhaps I can get to Moscow and take the letter personally. I will see...”

Surkhay in flat number three is working.

Sakina is crying quietly and bitterly in flat number two. Zahra gari is asleep. A dreamless sleep.

Domkom Bashir in flat number 1 is reprimanding his wife:

- “Don’t talk nonsense - he says –

Nobody is taken away unless they are guilty. Who knows what mistake he has made? –

Then he gives a deep sigh and adds: - Eh! If even Suleyman was mortal!

The door of flat number 8 opens. The steps go inside. After a while the steps are heard again.

They go down, floor by floor. The entrance door opens and then closes. The car starts up. It moves off. The sound of the car fades and disappears.

The street is silent, as if it has swallowed the noises.

The light leaks into the night from just one window of the block faded into the darkness. In the garden – on the bench over which a branch droops like a broken wing – the young man is kissing the girl on the li ps. Early in the morning domkom Bashir takes a brush and a bucket of paint and goes into the corridor.

There is a black board in the corridor with the names and surnames of the residents on it. Only the surname next to number 5 is blacked out and impossible to read. Domkom Bashir blacked it out two weeks ago. This morning, once again, domkom Bashir takes the black bucket and the brush and goes into the corridor.

It is seven o’clock.

The residents Sakina, Javanshir and Tavusm, who are rushing to work, meet in the corridor. They halt for a moment and look at domkom Bashir. Sakina shivers; she winds a scarf round her neck once more. Bashir kishi raises the brush towards the name “Zeynalli”.

Suddenly...

Javanshir and Tavus are startled. Sakina grasps the end of her scarf. Domkom Bashir is rooted to the spot in astonishment.

A slanting beam of light filters onto the grey cement floor from the entrance door. Through the partly open door can be seen part of the street, a window of the block opposite, green shoots sprouting on the window sill. However the people in the corridor are astonished by something else.

The occupier of flat number 8, oilman Murad Zeynalli, is standing in the doorway. Murad looks at domkom Bashir, the board, the brush, the bucket and immediately understands, but he does not move from the door.

Javanshir:

- “But ... you ... last night ... the car” – he mumbles.

Zuleykha, Bashir’s wife also comes to the door. She also looks at Murad and the people in the corridor with astonishment.

The sound of someone coming quickly down the stairs. The project papers under Surkhay’s arm are neatly rolled.

Surkhay is always grinning from ear to ear and all his healthy, snow-white teeth are on show.

Murad says:

- “Don’t think the worst. That was the ambulance. We took Farida to the maternity hospital. My son was born tonight.”

Tavus slaps her hand against her forehead, - “Wow, vakhsey!*, - she says. – I totally forgot. Farida was heavily pregnant.” Zuleykha:

- “Of course! It didn’t occur to any of us - she says – May Allah protect the child. May he grow up healthy! May Allah protect his parents!”

Javanshir turns yellow for some reason. Hastily takes out a cigarette.

Sakina blushes for some reason. Lowers her head.

There is a clatter, the brush has slipped out of Bashir’s hand.

Surkhay:

- “Congratulations, our best wishes” - he says and rushes out.

***

The child born that night was me.

***

There are different days every year, joyful days, sorrowful days.

Working days, holidays, funeral days. Our generation writes on forms: year of birth - 1937.

Only when we grew up did we discover that the year 1937 was a dark year and remains in people’s memories as a year of fear and anxiety.

But for us this year is the most important year of our life.

The year when we first saw the sun, the trees, the world.

Kishi* - a man

Domkom* (домовый комитет)

a community committee employee

Armudu* - pear-shaped

Qari* - an old woman

Vakhsey* - Goodness me!