Pages 12-15

Pages 12-15by Celia Davies

EC President Jose Barroso visits the Region

“Though I had many difficulties to fight against, it is certain that Nabucco was born under a lucky star.”

- Giuseppe Verdi (1842)

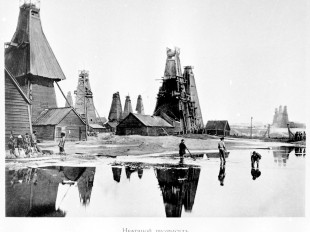

On a chilly autumn night one hundred and sixty years later, the Vienna State Opera rang with the libretto of Verdi’s most famous opera. In the audience sat a group of international energy investors, celebrating the successful conclusion of a long day’s negotiations. That day, they had written and signed a protocol of intention for the construction of a 4,042 km gas pipeline from Turkey to Austria. They would christen it Nabucco.

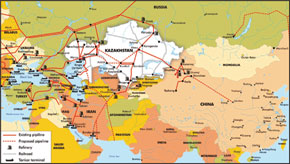

The proposed Nabucco pipeline will extend the existing South Caucasus Gas Pipeline (Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum), which carries natural gas from Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz gas field in the Caspian. It is central to the EU’s Southern Corridor energy strategy, which aims to diversify gas supply and transit routes.

The strategy as agreed at the Prague Summit of May 2009 includes Nabucco, the White Stream pipeline (under the Black Sea from Georgia to Romania), the Interconnector Turkey - Greece - Italy, and the Transadriatic Pipeline (Greece - Albania - Italy, running under the Adriatic).

Once the proposed lines of the Southern Corridor project are up and running, they will deliver the 60 to 120 billion cubic metres per year of Caspian and Central Asian gas that the European Commission wants to pipe directly to Europe. Nabucco’s projected final capacity is 31 billion cubic metres per year (bcm/yr). To put these numbers in perspective, Europe’s net requirement is around 500 bcm/yr. While no one claims Nabucco or the Southern Corridor will end Europe’s dependence on Russia, no one doubts that the Russians are apprehensive. January saw a flurry of comment on the news website ‘Voice of Russia’, much of which sought to dampen enthusiasm about the “notorious” Nabucco project.

This sudden anxiety reflects new developments in the Nabucco project. On 13 January, EC President Jose Barroso arrived in Baku for talks with President Aliyev. With him was Günther Oettinger, the Energy Commissioner, a sign that this was a visit with a very particular purpose. Barroso deemed the meeting “a major breakthrough”. Azerbaijan committed to supplying the EU with substantial volumes of gas over the long term. In terms of concrete promises, Aliyev has pledged 21 bcm/yr for the next five to eight years, which would be about two-thirds of Nabucco’s proposed capacity.

The remaining third, stakeholders hope, will come from Turkmenistan: Barroso and Oettinger flew from Baku to Ashgabat to meet with Turkmen President Berdymukhamedov. How strong is the commitment there? A press spokesman for Berdymukhamedov described the visit as “a step towards a more active dialogue between Turkmenistan and the EU”, and according to Jerome Pons, Head of Political Section for the EU Delegation to Azerbaijan, the EU wants to be “reasonably optimistic”, based on “commitment at the highest level”. Pons points out that this type of energy cooperation is unprecedented. “There has never been a time when all partners in the region have all been pushing in the same direction”.

Statement of integrity

For more than twenty years, Azerbaijan’s international relations have been coloured by the ongoing conflict with Armenia over the Nagorno-Karabakh territory. In fact, Barroso’s energy visit was no exception, and his remarks on the situation were immediately picked out by the Azerbaijani and Armenian press. There was much controversy after claims that Barroso’s live comments about “supporting the territorial integrity” of Azerbaijan were omitted from the official EU website. The Azerbaijani foreign ministry issued a protest statement which expressed “feelings of regret and surprise [that] might call into question mutual confidence and cooperation with the European Union.”

Regardless of this upset, what is unarguable is that Nabucco corresponds to the mutual interests of Azerbaijan and the EU, and captures a vision of how EU-Azerbaijan relations may develop over the next twenty years. Azerbaijan has declared significant gas resources and its desire to export to Europe’s stable, rule-based economy of 500 million people. The EU is aware of its commitment to reduce carbon emissions by 2020, which means cutting oil and coal-based energy production. Given that Caspian gas production seems to be on the up, this is all good news. Last November, for example, the Azerbaijan State Energy Company discovered 200 bcm at the Umid (Hope) gas field. The Southern Corridor will help both the EU and Azerbaijan put their eggs in more baskets: just as the EU wants to diversify its energy sources, Azerbaijan is trying to diversify its trade with the EU, which is currently 90 per cent in oil.

Diversification

The diversification of sources and routes is very much present in the declaration signed by Aliyev and Barroso, which highlights the importance of energy security. The 2006-2009 Russia-Ukraine gas disputes badly frightened Europe, and spurred on the search for alternatives routes and supplies. In January 2009, pricing conflicts reached crisis point and Russia cut off all gas supplies to the Ukraine- resulting in a pipeline pressure drop in several European countries. The European Union as a whole gets around 20 per cent of its gas from Russia, and about 80 per cent of that comes via pipelines crossing Ukraine. In a statement at the time, Barroso made a “call on member states to engage in a concerted action to find alternative ways of energy supply and transit.” A quick look at gas supply figures explains this urgency. As of 2009, the Russian gas monopoly, Gazprom, supplied Europe with 65 per cent of its imported natural gas (and, as mentioned above, around 20 per cent of the EU’s net requirement). Most of the remaining 35 per cent comes from Algeria. Thanks to North Sea reserves, the UK does not rely upon Russian imports- but other EU countries are very much beholden. Germany, for example, gets about 39 per cent of its total annual demand from Gazprom - and there are member states that in 2009 were 100 per cent dependent on Russian gas: Slovakia, Finland, and Bulgaria. In addition to security concerns, there is the issue of demand. European Commission researchers expect that Europe’s gas consumption will increase from 502 billion cubic metres in 2005 to 815 billion cubic metres in 2030 and, in that case, Russian supplies would not be able to keep up with demand.

It is noteworthy but not surprising, therefore, that the recent agreement is concerned to emphasise speed: “our common objective is to see the Southern Corridor established and operational as soon as possible”, and to “urge a swift allocation process for the available gas resources” and to “encourage investors to take all possible measures for the joint allocation of that gas in a timely manner”. According to Azerbaijani media sources, Oettinger has said that the pipeline will be functioning within the next two to three years.

While Russia has no real cause for concern in terms of losing its position as Europe’s most important source of gas, the dynamic of the energy sector looks set to shift dramatically. One of the sources of frustration for the EU has been the massive politicisation of these developments. Jerome Pons stresses that this is absolutely not a piece of political theatre or any kind of anti-Russian manoeuvre. Yes, the EU is interested in energy cooperation, but not for its own sake. Its foremost interest is gas - and gas at market prices. This has to be a competitive project to warrant EU involvement and investment. Nabucco, and the whole Southern Corridor project, is no less subject to economic selection than any other EU initiative.

For the long-term

Pons also point out that the EU’s interest in Azerbaijan predates the oil and gas boom. “We are not newcomers to the country or to the region, and we are not simply jumping on the energy bandwagon. We were here back in the early nineties, right after the breakup of the Soviet Union.” At that point, the EU was implementing projects across the newly independent states to support the development of market economies and democratic societies. Pons believes that the EU’s image in Azerbaijan is often maligned. “The way that trade works means that, of course, oil and gas will drive the economic side of things, but we are interested in many aspects of development here.”

He doesn’t expand upon this, but a little bit of digging reveals one possible area for expansion: renewable energy. Azerbaijan offers excellent natural conditions for wind, solar, hydro power, and possibly geothermal energy sources. In the summer of 2010, the government set up a state agency on “Alternative and Renewable Energy Sources”. Several international donors and implementation agencies are helping out with legal frameworks, economic incentives, scientific studies on technological requirements, management of pilot investment projects and campaigns to raise awareness. And things are already happening here - wind farms, solar powered water purification units in rural areas and solar powered water heating facilities are all under development.

The future for the Azerbaijani energy sector looks promising- and if the country plays its cards right, it could be that the real energy boom hasn’t even happened yet…