Pages 8-12

by Mais Amrahov

Ancient origins

The word bayrag (flag) is Turkic in origin. It is mentioned in the 11th century dictionary Divani-lugat-it-turk (dictionary of the Turkish language) of Mahmud Kashkarli, both in the modern meaning and in literal meanings of the word bayrak – batrak. The word bayrag has the same meaning in most ancient and modern Turkic languages. Batrak, bayrak originated from the verb ‘to stick in’, to thrust (batir – batirmaq, sanjmag). Alongside bayrag other words were also used to mean flag: tugra, bunjug, sanjag - which also arose from the verb meaning to thrust (sanjmag).

Archaeological finds in Azerbaijan confirm that flags to be used as standards were present even in the Bronze Age (4th – 2nd Millennium B.C.). Circular bronze boards and bronze standards in other shapes, decorated with various geometrical figures, such as a horned deer, an eight-pointed star and a radiant sun, were found during archaeological excavations carried out in Shaki and Shamkir; they were probably the symbols of the head of a tribe or ruling authority. Most of the standards found carried images of horned animals. These are also encountered in Assyrian reliefs of the 8-7 centuries B.C., depicting fortresses in Manna. Standards in these shapes probably served as talismans. In today’s Azerbaijan, the horns of goats and rams, animal skulls (dogs, horses, deer) are still fastened above gates and doors and used as symbols or talismans to protect against ‘the evil eye’ and malevolent deeds.

The Azerbaijani flag has an ancient history. The Albanian historian, Musa Kalankatli in his work, History of Albaniya devoted a section to the images of flags. The bodies of these flags were shaped as dragons or birds and were made from silk. Their shafts were made from silver and depicted the heads of mythical animals. Similar flags were widespread in Europe and other Eastern countries in the Middle Age.

Flags had a military significance. They were particularly protected during battles, their fall or capture by the enemy meant defeat. In the Book of Dede Gorgud Salur Gazan, who succeeded to taking vengeance for an attack by enemies, “cut the sanjag (the flag) of the kaffir with his tugh (sword) and threw it to the ground”. The images of a lion and a human face in the shape of the Sun (Shiri-Khurshid) on the background of the flag of the Safavids’ state, which was especially prominent in the history of Azerbaijani statehood, shows that the state was based on national traditions and ancient history.

The Azerbaijani khanates also had special flags. These flags were removed from Azerbaijan during the Russian occupation by various routes in the early 19th century and were later passed to the Caucasian Military Museum in Tbilisi.

Flags come home

In April 1919, during the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, the question of returning flags which reflected the history of Azerbaijani statehood to their homeland was raised. Minister of Defence General Samad bey Mehmandarov, instructed Lieutenant Colonel Mammadbey Aliyev the Azerbaijan attaché in Georgia, to obtain the Georgian government’s consent to return to Baku the Azerbaijani flags and other symbols of state that were held in the Tbilisi Museum. This question was raised again at the First All-Azerbaijani Congress of Local History (September 1924) after the establishment of the Azerbaijan State Museum in June 1920. In the same year, the State Museum of History succeeded in obtaining the flags of the khanates, of Azerbaijani generals who had served in the tsarist army and of certain Muslim regiments.

The President of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, and first lady Mehriban Aliyeva at the newly established State Flag Square Museum

The flags of the Azerbaijani khanates were triangular, quadrangular, and pentagonal in shape, were sewed from fine eastern fabric and decorated with various ornaments and inscriptions. They were fringed with silk thread of different colours as well as with gold and silver thread. The shafts were cylindrical and were made from light wood; they were painted, their tops were decorated with decorated metal caps and tassels made from thread of gold, silver and other colours were attached.

The flag of the Ganja khanate was rectangular in shape and was made from a specially knitted fabric 127 cm long and 174 cm wide. The flag was sewn manually from a crimson and green moiré fabric. At the top of the flag there were three bunches of gold-coloured flowers and a scarlet oblong, on the right two golden oblongs. The Arabic word Allah was written inside the scarlet oblong and surrounded by gold lilies.

The rectangular flag (220 cm long, 127 cm wide) of the Baku khanate was sewn manually from four pieces of light crimson and one piece of light moiré fabric. A piece of green fabric (31 cm wide) placed lengthwise, was fastened via the red satin border (6 cm wide). On the first stripe, inside two light and dark butas (‘paisley’ pattern) were ornaments of six-sided flowers similar to lilies, placed side by side and top to tail, and pointed, undulating, leaf-like patterns.

The second stripe was wider. On this there were two crescents in light and dark green; their ends were joined. Six- and eight-pointed flowers were embroidered inside the circle created by the joining of the crescents. The rest of the flag was also embroidered with various ornaments.

In general, the flags of the khanates differ in size, style and ornamentation. Silk thread in various colours was generally used.

Slightly later, after the Turkmenchay agreement (1828) was concluded between Russia and Iran, which resulted in the division of Azerbaijani lands, six Muslim regiments were formed from the population of Muslim provinces in the Southern Caucasus, including Azerbaijanis and the Kengerli cavalry unit. The battle flags of the regiments, distinctive in their patterns and political symbolism, were made from silk fabric of various colours with the Russian double-headed eagle depicted on them. There were inscriptions in Arabic on the flags.

The flags of the Muslim cavalry regiments were also noted for their fabric, design and decoration. The flags of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th etc. sotnias (squadrons) were made from fine taffeta. The Russian expression “Transcaucasian Regiment: 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and etc. sotnias” was written on them in patchwork, in large capital letters in the Cyrillic alphabet.

Attractive religious flags were made at the end of the 19th century and the early 20th century for use in religious ceremonies.

Birth of the modern state flag

During the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR), the first government resolution on the state flag was issued in July 1918. By this resolution, a white crescent and eight-pointed star were depicted on the state flag, which was basically red. This flag was only slightly different from that of the Ottoman Empire. This was misunderstood at the time and Azerbaijan began to be thought of as part of Turkey. So the government of the ADR decided to change the image. The Cabinet’s resolution read: “A flag consisting of the colours green, red and blue with a white crescent and eight-pointed star is to be considered the National flag”. Thus, on 9 November 1918, the three-colour flag of Azerbaijan was accepted as the State Flag.

The Azerbaijani flag consisted of three stripes of equal width. The upper stripe was blue, the middle stripe was red and the lower stripe was green. In the middle of the red stripe on both sides of the flag were depicted a white crescent and eightpointed star. The ratio of the flag was 1:2. The blue colour expressed Turkism, the red colour meant modernity and the green colour stood for Islam.

The crescent has been the emblem of Turks from ancient times. In Azerbaijani mythology, the moon is a male symbol and the star is a female symbol. The moon was also the emblem of Caucasian Albania. The priests of the Moon temple were regarded as the most holy men in Albania after the ruler. There are some explanations for the combination of the crescent and the eight-pointed star. According to the ADR it was an allusion to equality of rights for men and women. It was also seen as a symbol of happiness.

There is another explanation, that the eight-pointed star reflects the writing of the word “Azerbaijan” in the old alphabet. According to another version, the eightpointed star represented the “eight doors of Paradise”.

After the Bolsheviks seized power, the ADR collapsed. The Soviet era began (1920-1991). During that time the image of Azerbaijan’s flag was changed several times. At different periods there were different flags. From 1921-1925, on the upper left side of the red fabric ,SSRA was written in green material, from 1925-1931, on the upper left side of the red fabric, there were images of the hammer and sickle, a crescent and five-pointed star above them and the acronym SSRA written in Cyrillic and Arabic. From 1931-1937, it was a red banner with the hammer and sickle on the upper left side, a crescent and fivepointed star above them and the acronym SSRA written in Cyrillic. From 1937-1940, a flag with the hammer and sickle on the upper left side of the red banner and the acronym Az. SSR was in use. From 1940- 1952, a flag with the hammer and sickle on the upper left side of the red fabric and the acronym Az.SSR below it was used. From 1952-1991 the flag was red, with a hammer and sickle and a five-pointed star, and a blue stripe at the foot.

Military divisions participating in World War II, including Azerbaijani divisions, military units, regiments, sections and fleets, all had their own flags.

National parties, political organisations and societies and educational enterprises also had flags.

In spite of all the prohibitions by the USSR’s totalitarian regime, Azerbaijanis living here, as well as those who had migrated abroad, never forgot the threecolour flag; it was held in the national memory.

In 1956, Jahid Hilaloglu raised the three-colour flag on Maiden Tower as a protest against the existing Soviet regime. He was imprisoned for four years for this action and his accomplice was placed in a special clinic for mental patients.

The three-colour flag was waved again as a symbol of independence during the national liberation movement which began in 1988.

‘A flag once raised will never fall’

So said Mammad Amin Rasulzade, one of the founders of the ADR in 1918, and the flag was again given legal status by Heydar Aliyev. Thus, on 17 November 1990 on his initiative, the Supreme Mejlis (Assembly) of the Autonomous Republic of Nakhchivan accepted the three-colour flag as its state flag and presented a petition to the Supreme Soviet of the SSR of Azerbaijan to recognise the three-colour flag as the of- ficial state symbol of Azerbaijan. Finally, on 5 February 1991, the Supreme Soviet passed a “Law of the Republic of Azerbaijan on the State Flag of the Republic of Azerbaijan”, shortly afterwards the “Constitutional Act on the State Independence of the Republic of Azerbaijan” was approved.

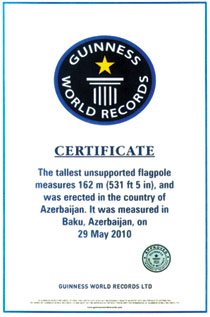

On 17 November 2007 the president of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, signed a directive to create State Flag Square in Baku. In December of the same year, the foundation of State Flag Square was laid near the Naval Base in the Bayil settlement of Baku. The directive defined the dimensions of the state flag as follows: the flagpole is 162 metres high, the flag’s dimensions are 35x70 metres, its area 2,450 square metres, its weight 350 kg. The ceremonial opening of State Flag Square took place on 1 September 2010. The flag of Azerbaijan is a symbol of the independence and freedom of the Azerbaijani nation.

The flag of Azerbaijan is the state’s emblem and its moral and political passport.

About the author: Mais Amrahov is a professor in the “Department of History of Turkic and Eastern Europe nations and History Teaching Methodology” at the Azerbaijan State University of Teacher Training and a PhD in History. He is the author of monographs and articles devoted to World War II and the modern history of Azerbaijan.

by Mais Amrahov

Ancient origins

The word bayrag (flag) is Turkic in origin. It is mentioned in the 11th century dictionary Divani-lugat-it-turk (dictionary of the Turkish language) of Mahmud Kashkarli, both in the modern meaning and in literal meanings of the word bayrak – batrak. The word bayrag has the same meaning in most ancient and modern Turkic languages. Batrak, bayrak originated from the verb ‘to stick in’, to thrust (batir – batirmaq, sanjmag). Alongside bayrag other words were also used to mean flag: tugra, bunjug, sanjag - which also arose from the verb meaning to thrust (sanjmag).

Archaeological finds in Azerbaijan confirm that flags to be used as standards were present even in the Bronze Age (4th – 2nd Millennium B.C.). Circular bronze boards and bronze standards in other shapes, decorated with various geometrical figures, such as a horned deer, an eight-pointed star and a radiant sun, were found during archaeological excavations carried out in Shaki and Shamkir; they were probably the symbols of the head of a tribe or ruling authority. Most of the standards found carried images of horned animals. These are also encountered in Assyrian reliefs of the 8-7 centuries B.C., depicting fortresses in Manna. Standards in these shapes probably served as talismans. In today’s Azerbaijan, the horns of goats and rams, animal skulls (dogs, horses, deer) are still fastened above gates and doors and used as symbols or talismans to protect against ‘the evil eye’ and malevolent deeds.

The Azerbaijani flag has an ancient history. The Albanian historian, Musa Kalankatli in his work, History of Albaniya devoted a section to the images of flags. The bodies of these flags were shaped as dragons or birds and were made from silk. Their shafts were made from silver and depicted the heads of mythical animals. Similar flags were widespread in Europe and other Eastern countries in the Middle Age.

Flags had a military significance. They were particularly protected during battles, their fall or capture by the enemy meant defeat. In the Book of Dede Gorgud Salur Gazan, who succeeded to taking vengeance for an attack by enemies, “cut the sanjag (the flag) of the kaffir with his tugh (sword) and threw it to the ground”. The images of a lion and a human face in the shape of the Sun (Shiri-Khurshid) on the background of the flag of the Safavids’ state, which was especially prominent in the history of Azerbaijani statehood, shows that the state was based on national traditions and ancient history.

The Azerbaijani khanates also had special flags. These flags were removed from Azerbaijan during the Russian occupation by various routes in the early 19th century and were later passed to the Caucasian Military Museum in Tbilisi.

Flags come home

In April 1919, during the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, the question of returning flags which reflected the history of Azerbaijani statehood to their homeland was raised. Minister of Defence General Samad bey Mehmandarov, instructed Lieutenant Colonel Mammadbey Aliyev the Azerbaijan attaché in Georgia, to obtain the Georgian government’s consent to return to Baku the Azerbaijani flags and other symbols of state that were held in the Tbilisi Museum. This question was raised again at the First All-Azerbaijani Congress of Local History (September 1924) after the establishment of the Azerbaijan State Museum in June 1920. In the same year, the State Museum of History succeeded in obtaining the flags of the khanates, of Azerbaijani generals who had served in the tsarist army and of certain Muslim regiments.

The President of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, and first lady Mehriban Aliyeva at the newly established State Flag Square Museum

The flags of the Azerbaijani khanates were triangular, quadrangular, and pentagonal in shape, were sewed from fine eastern fabric and decorated with various ornaments and inscriptions. They were fringed with silk thread of different colours as well as with gold and silver thread. The shafts were cylindrical and were made from light wood; they were painted, their tops were decorated with decorated metal caps and tassels made from thread of gold, silver and other colours were attached.

The flag of the Ganja khanate was rectangular in shape and was made from a specially knitted fabric 127 cm long and 174 cm wide. The flag was sewn manually from a crimson and green moiré fabric. At the top of the flag there were three bunches of gold-coloured flowers and a scarlet oblong, on the right two golden oblongs. The Arabic word Allah was written inside the scarlet oblong and surrounded by gold lilies.

The rectangular flag (220 cm long, 127 cm wide) of the Baku khanate was sewn manually from four pieces of light crimson and one piece of light moiré fabric. A piece of green fabric (31 cm wide) placed lengthwise, was fastened via the red satin border (6 cm wide). On the first stripe, inside two light and dark butas (‘paisley’ pattern) were ornaments of six-sided flowers similar to lilies, placed side by side and top to tail, and pointed, undulating, leaf-like patterns.

The second stripe was wider. On this there were two crescents in light and dark green; their ends were joined. Six- and eight-pointed flowers were embroidered inside the circle created by the joining of the crescents. The rest of the flag was also embroidered with various ornaments.

In general, the flags of the khanates differ in size, style and ornamentation. Silk thread in various colours was generally used.

Slightly later, after the Turkmenchay agreement (1828) was concluded between Russia and Iran, which resulted in the division of Azerbaijani lands, six Muslim regiments were formed from the population of Muslim provinces in the Southern Caucasus, including Azerbaijanis and the Kengerli cavalry unit. The battle flags of the regiments, distinctive in their patterns and political symbolism, were made from silk fabric of various colours with the Russian double-headed eagle depicted on them. There were inscriptions in Arabic on the flags.

The flags of the Muslim cavalry regiments were also noted for their fabric, design and decoration. The flags of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th etc. sotnias (squadrons) were made from fine taffeta. The Russian expression “Transcaucasian Regiment: 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and etc. sotnias” was written on them in patchwork, in large capital letters in the Cyrillic alphabet.

Attractive religious flags were made at the end of the 19th century and the early 20th century for use in religious ceremonies.

Birth of the modern state flag

During the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR), the first government resolution on the state flag was issued in July 1918. By this resolution, a white crescent and eight-pointed star were depicted on the state flag, which was basically red. This flag was only slightly different from that of the Ottoman Empire. This was misunderstood at the time and Azerbaijan began to be thought of as part of Turkey. So the government of the ADR decided to change the image. The Cabinet’s resolution read: “A flag consisting of the colours green, red and blue with a white crescent and eight-pointed star is to be considered the National flag”. Thus, on 9 November 1918, the three-colour flag of Azerbaijan was accepted as the State Flag.

The Azerbaijani flag consisted of three stripes of equal width. The upper stripe was blue, the middle stripe was red and the lower stripe was green. In the middle of the red stripe on both sides of the flag were depicted a white crescent and eightpointed star. The ratio of the flag was 1:2. The blue colour expressed Turkism, the red colour meant modernity and the green colour stood for Islam.

The crescent has been the emblem of Turks from ancient times. In Azerbaijani mythology, the moon is a male symbol and the star is a female symbol. The moon was also the emblem of Caucasian Albania. The priests of the Moon temple were regarded as the most holy men in Albania after the ruler. There are some explanations for the combination of the crescent and the eight-pointed star. According to the ADR it was an allusion to equality of rights for men and women. It was also seen as a symbol of happiness.

There is another explanation, that the eight-pointed star reflects the writing of the word “Azerbaijan” in the old alphabet. According to another version, the eightpointed star represented the “eight doors of Paradise”.

After the Bolsheviks seized power, the ADR collapsed. The Soviet era began (1920-1991). During that time the image of Azerbaijan’s flag was changed several times. At different periods there were different flags. From 1921-1925, on the upper left side of the red fabric ,SSRA was written in green material, from 1925-1931, on the upper left side of the red fabric, there were images of the hammer and sickle, a crescent and five-pointed star above them and the acronym SSRA written in Cyrillic and Arabic. From 1931-1937, it was a red banner with the hammer and sickle on the upper left side, a crescent and fivepointed star above them and the acronym SSRA written in Cyrillic. From 1937-1940, a flag with the hammer and sickle on the upper left side of the red banner and the acronym Az. SSR was in use. From 1940- 1952, a flag with the hammer and sickle on the upper left side of the red fabric and the acronym Az.SSR below it was used. From 1952-1991 the flag was red, with a hammer and sickle and a five-pointed star, and a blue stripe at the foot.

Military divisions participating in World War II, including Azerbaijani divisions, military units, regiments, sections and fleets, all had their own flags.

National parties, political organisations and societies and educational enterprises also had flags.

In spite of all the prohibitions by the USSR’s totalitarian regime, Azerbaijanis living here, as well as those who had migrated abroad, never forgot the threecolour flag; it was held in the national memory.

In 1956, Jahid Hilaloglu raised the three-colour flag on Maiden Tower as a protest against the existing Soviet regime. He was imprisoned for four years for this action and his accomplice was placed in a special clinic for mental patients.

The three-colour flag was waved again as a symbol of independence during the national liberation movement which began in 1988.

‘A flag once raised will never fall’

So said Mammad Amin Rasulzade, one of the founders of the ADR in 1918, and the flag was again given legal status by Heydar Aliyev. Thus, on 17 November 1990 on his initiative, the Supreme Mejlis (Assembly) of the Autonomous Republic of Nakhchivan accepted the three-colour flag as its state flag and presented a petition to the Supreme Soviet of the SSR of Azerbaijan to recognise the three-colour flag as the of- ficial state symbol of Azerbaijan. Finally, on 5 February 1991, the Supreme Soviet passed a “Law of the Republic of Azerbaijan on the State Flag of the Republic of Azerbaijan”, shortly afterwards the “Constitutional Act on the State Independence of the Republic of Azerbaijan” was approved.

On 17 November 2007 the president of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, signed a directive to create State Flag Square in Baku. In December of the same year, the foundation of State Flag Square was laid near the Naval Base in the Bayil settlement of Baku. The directive defined the dimensions of the state flag as follows: the flagpole is 162 metres high, the flag’s dimensions are 35x70 metres, its area 2,450 square metres, its weight 350 kg. The ceremonial opening of State Flag Square took place on 1 September 2010. The flag of Azerbaijan is a symbol of the independence and freedom of the Azerbaijani nation.

The flag of Azerbaijan is the state’s emblem and its moral and political passport.

About the author: Mais Amrahov is a professor in the “Department of History of Turkic and Eastern Europe nations and History Teaching Methodology” at the Azerbaijan State University of Teacher Training and a PhD in History. He is the author of monographs and articles devoted to World War II and the modern history of Azerbaijan.