Pages 38-45

by Shirin Bunyadova

Knock on any door...

Azerbaijan’s customs of hospitality are very revealing of the culture and the spirit of the world in which its people live. These customs tell us much about the people who live in this land and their potential. Alexandre Dumas wrote about Azerbaijani hospitality and also of the Caucasus peoples: “If you knock on any door in Azerbaijan, or anywhere in the Caucasus, say that you’re a foreigner and have no place to spend the night, the owner of the house will immediately give you his largest room. He and his family will move to the small room. Moreover, during the week, two weeks, or the month that you stay in his house he will take care of you and will not let you want for anything”.

Azerbaijanis consider it a duty to show infinite respect for a guest. The guest is sacred in Azerbaijan and the tradition of respect is taken very seriously.

The great 12th century Azerbaijani poet Nizami Ganjavi returned often to the noble custom of hospitality in his works. He wrote in his work “Yeddi Gozel” (The Seven Beauties):

She was welcoming as a garden flower,

Her smile was the bud of a rose.

Her palace was prepared for guests

And it reached to the skies

She laid a table and arranged a celebration,

Her servants were raised in grace.

For each new arrival, they held his horse’s bridle,

They laid the table according to rule.

They showed him courteous hospitality,

And dined him according to his rank.

In Nizami Ganjavi’s writings, hospitality is clearly seen as a custom routine in the everyday life of the Azerbaijani people.

Every household in Azerbaijan (within their means, sometimes even beyond their economic means) believed it their duty and a matter of honour to receive their guest with great respect, entertain him and send him on his way. This was not a tradition restricted to acquaintances only. It also applied to strangers, people who did not know each other at all and travellers on a journey.

In Azerbaijan hospitality acquired a certain status, took on a moral quality and became an internal instinct.

That is to say, regardless of whether the guest was personally invited or whether the householder knew him, everyone regarded a visitor to their country as their personal guest and felt bound to receive him and see him off sincerely. This is a distinctive feature of our people. The custom of hospitality seems simple enough, but it has specific requirements and can be quite demanding. Thus, it takes much effort and attention on the part of the householder to do the job thoroughly of receiving a guest, hosting him and seeing him off appropriately.

Guest: first and foremost

Even if an enemy steps into one’s house in Azerbaijan, no retribution may be exacted; as a guest he is untouchable. Eastern hospitality rises above all other customs of everyday life.

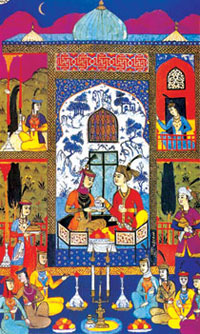

The householder would even set a guard to protect a guest whose life was in danger and who asked for help; as well as providing comfort, the safety of a guest was all part of the responsibility. This extended, of course, to protection of the guest’s belongings. All household members saw the guest off,  Miniature showing Khagan receiving Iskender as a guest, Nizami’s ‘Iskendername’ (Isfahan, 1560-1570) but the host would always suggest that the stay be prolonged a little.

Miniature showing Khagan receiving Iskender as a guest, Nizami’s ‘Iskendername’ (Isfahan, 1560-1570) but the host would always suggest that the stay be prolonged a little.

As a mark of respect, the householder followed the departing guest with his eyes until he was out of sight. However, if the guest had a request or a wish when he was leaving the house, naturally, the host did his best to fulfil it and, if need be, he would expect to walk the guest to a staging post or take him to his destination.

There is a tradition in Azerbaijan that if a passer-by, even a complete stranger, says that he is a guest, a householder must serve him with all his heart and soul. Often, not only the house owner but also his relatives, consider it their duty to invite the guest to their place.

All household members were prepared for the sudden arrival of a guest. One or two extra portions of every meal would be prepared for just such an eventuality. In the past, a group of horsemen would meet high-level guests. Foreign guests were the centre of special attention and all influential people in the locality would call and invite them to their homes.

Azerbaijani households kept either a separate building or a room in the house as a guest room. Children were not allowed in there. If the visitor had a horse, even this was allocated a special place and well looked after.

In general, it was thought improper for the host to tire a guest with many questions, to ask why he had arrived or when he would leave. Only after the newcomer had said who he was and announced his purpose would the household rally round to provide all he needed.

Guests were freely given food, a room and a bed.

Each household member had a specific responsibility for the guest. The householder always ensured there were reserves of food and provisions.

Lay a good table...

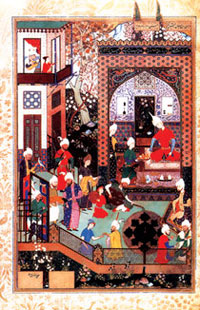

From the earliest of times, a banquet would be held to honour a visitor, the table was laid and festivities began.

The guest was placed at the head of the table. Next to him sat the elder of the house, then other respected elders and people. Only adults could engage in conversation. It was not thought right to talk too much at the table during banquets and all had to know their place. The host also arranged for a selection of meals to appear on his banquet table.

The table on such occasions was laden with more delicious and abundant meals than for the everyday meal. The drinks served were sherbet and ayran (a diluted yoghurt drink – ed.) and, in some cases, wine. The meals served at a banquet table were mainly of rice and meat, accompanied by herbs. Along with different types of sweetmeats, jams etc., fruit was also served as dessert.

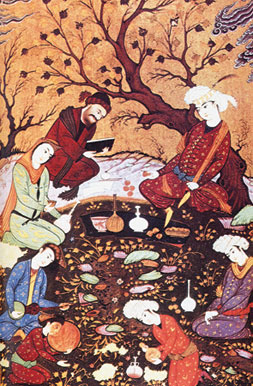

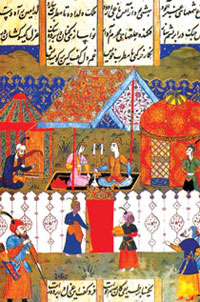

As a rule, banquets were accompanied by music – as confirmed by miniature paintings, which indicate that a special corner was set aside for musicians. For the sound to carry, the musicians would sing on the lower floor of a house, or from some distance within a tent.

Tradition decreed that it was impolite not to listen to the music at banquets, to ignore it or to talk a lot.

A common part of traditional hospitality was to give presents to the guest. The guest would offer a gift to the host and, in turn, the householder would send the guest off with other presents. This custom has survived to the present day.

The celebrated 17th century Turkish traveller and geographer Evliya Celebi described his reception in Azerbaijan, the banquet table and the presents given to guests: “During the banquet, a kalamkari (hand-printed – ed.) tablecloth was laid. Eleven types of plov (pilaf – ed.) were served: and soup, we ate tasty meals and had good conversation.

After the banquet, the guest, I and small Hasanagaya were given fine lynx leather. From there we went down to our tent. He sent us about 50 sheep, some 1,000 loaves of white bread, seven to eight mules of fruit and sherbet. That night we had a huge celebration; we stayed another two days there and had a look at the beautiful palaces on the bank of the river Qarsi.”

According to tradition, a man’s best quality is generosity, demonstrated by his ability to lay a good table and give a banquet for visitors to his house. People say that a generous person’s prosperity comes from Allah.

Guest for one, guest for all

When the householder is unable to provide a good reception for a guest, people help him. At this time, relatives and neighbours will help poor families. Thus hospitality goes beyond the limited framework of a household and becomes a collective effort. Good relations can be formed by benevolence and lending each other a helping hand is accepted as a moral law and the most honourable thing to do.

According to a folk custom, after receiving the guest it is advisable to leave him by himself for some time to rest, adjust and make himself comfortable. However, this should not be for too long, because one should not be inattentive to one’s guest. If the guest is a stranger and his stay is temporary, the house owner will not think it right to stay too long by his side, so as not to tire him.

The time of arrival also helps determine the rules. Thus, if the guest arrives in the evening, he is given food and a bed made up quickly. If the guest is someone close, an acquaintance or a relative, in this case the house owner naturally prefers greater contact. In this case, not only the house owner but also his relatives assemble and entertain the guest and fulfil the smallest of his wishes with enthusiasm. The guest becomes one of the family.

Since travellers were often not familiar with the country and the roads, naturally, as a sign of special attention to and care for travellers, they were given guides to enable them to continue their journey in comfort. The guide would not restrict himself to merely accompanying the guest on their journey but he would arrange meals and help with other things, too.

Decorating the guest house or room was by no means a formality. The interior of the house or guest room was decorated in the best taste. During the guest’s stay, everything in there was his. This meant that every single item in the room was for the guest’s use and at his disposal.

Hospitality during holidays is special. It is still a tradition, a duty and a good deed to invite a guest for a meal to break the fast during Ramazan, or to visit others to take them sweets and, during the Festival of Sacrifice (the Gurban Bayram holiday – ed.) to take some sacrificial meat (usually lamb) to close relatives and neighbours.

Thus, along with abstaining from food during these holidays, giving an evening meal to those fasting during the day and distributing the meat of sacrificial animals brings people closer together. The Novruz holiday is a particular time for visiting, when people settle quarrels and hand out presents and sweets.

Historically hospitable

The 17th century Dutch traveller Jan Struys, who attended Novruz holiday ceremonies, wrote of dashing in the company of aristocrats to eat now in one Azerbaijani’s place and now in another’s.

Visitors from various countries to Azerbaijan normally commented in their reports about how the local population received them and saw them off. This confirms once again the high level of hospitality in Azerbaijan. The 16th century Venetian Michele Membre often visited the houses of people that Shah Tahmasib made responsible for him in Tabriz. He noted that “all these people were pleased to talk to me, freely took me to their homes and sometimes allowed me to stay there for 15 to 20 days. They are pleased to hear about developments in Europe because they do not know anything about these countries....Their meals are similar to those of Turks but they are more generous and open-hearted and they give people food at their homes more often than the Ottomans do.” This indicates the hospitality developed over the centuries and is characteristic of our people. The primary indicator of hospitality is the laying of the table and its adornment with many dishes. This is the breaking of bread and sharing it equally with someone else.

The 15th century Venetian ambassador Ambrogio Contarini was greeted with gifts on his arrival in Isfahan. He writes with enthusiasm about the hospitality with which Uzun Hasan received him and Giosafat Barbaro, whom he invited to his palace in Isfahan in November 1474: “when we entered the room, we saw the shah surrounded by his courtiers.

According to the local custom, I bowed my head and he gestured that I sit on the carpet. Afterwards, we were served various delicious dishes cooked according to local custom. Then we parted. He invited us again. He kindly showed us his palace built on the bank of a river. Here, too, he treated us to different kinds of sweets.

Uzun Hasan invited us round often. Sometimes, we happened to eat in his marquee. The meals which came in bowls were served in large helpings and they were excellent. When we were not near Uzun Hasan, he often sent us various consumer goods. I was also quickly provided with a house.”

Anthony Jenkinson also wrote about the high level of hospitality in Azerbaijan. An English merchant and sailor, Jenkinson embarked upon a major sea journey in the 16th century and visited Azerbaijani territory. In his memoirs, he also provides information about the custom of hospitality here.

Thus he notes that he was sincerely and very well received when he was a guest of Abdulla khan in Shemakha. He writes about how he was invited to lunch. As a sign of respect, he was shown to a seat near the host. He notes that an expensive carpet was laid on the floor and that people were sitting on the floor with their legs folded. “When they saw that I was not used to sitting like that, a table was specially brought for me. A tablecloth was laid and various dishes were brought. There were about 140 of them. When they were removed, in its stead they laid a table full of fruit and adorned with other meals (there were about 150 of these). I was bid ‘welcome’ there. The next day, I was invited to go hunting. The hunting was fun. Upon our return, they presented me with long garments sewn according to their tradition; they put the garments on me and took me to the khan. I kissed his hand. Then, he seated me next to himself and we had lunch together. During the conversation, he inquired about how the hunting had gone. Upon my return, he gave me an excellent horse as a gift. He even gave me a guide and a watchman for the continuation of my journey. Finally, when we got to Ardebil, we were placed in a caravanserai built from white stone and designed for foreigners and other travellers. Everyone here is provided with food and feed for the horses.”

Home stays and caravanserais

There was a separate building for guests in the courtyards of rich and wealthy people. They were normally built in a convenient part of a common courtyard. This was especially important in places with no caravanserais (mainly in mountainous regions and villages). The construction of a separate house for guests indicates the importance of hospitality in our country. They were built with particular attention to their appearance, beauty and comfort as a reflection of both the house owner’s taste and his respect for a guest. The decoration of the house or the room allocated to the guest was meant to ensure his comfort and complete freedom: carpets were a special feature. In addition, there was bedding and sometimes even a musical instrument. The householder bore great responsibility for the guest but, at the same time, the guest’s presentation and manners were also important. Acting in line with the rules of propriety, maintaining self-control and behaving according to the customs of the alien environment he was in were the guest’s responsibilities. The guest was absolutely not expected to interfere in the family’s internal affairs or intervene inappropriately.

Like many oriental countries, Azerbaijan also had caravanserais. They were located in towns and on important commercially significant routes and were widespread in their capacity as hotels. There were more of them in large trading centres. There was a certain similarity in the construction of caravanserais in all areas of Azerbaijan. Along with rooms for relaxation, caravanserais also had a canteen, mangers, storage facilities, shops etc.

Home-style caravanserais, which were places of temporary shelter, usually served guests arriving in Azerbaijani territory. Most of the travellers and merchants who visited Azerbaijan at various times and travelled through the country spoke of the presence of such caravanserais and remarked on their interior and exterior appearance.

Cleanliness next to...

In Azerbaijan, too, as in a number of Muslims countries, Shari’ah rules applied and this was directly evident as regards hospitality. For example, according to Shari’ah, “hands should be washed and wiped with a towel before and after eating”.

Also, unlike in the West, guests in the Muslim East did not retreat to a special room or corner to wash their hands. Water in an elegant container, and a bowl, were brought to guests at the table. The guests washed their hands without leaving their places.

This is how hands should be washed according to the etiquette: after the first of the guests washes his hands, next is the one sitting to his right. Thus, all of them take turns to wash their hands. After they have eaten, a parch (a type of metal jug – ed.) and a bowl are also brought. The guest who was last to wash his hands before eating is the first to wash his hands after eating. As a rule, a servant or the host’s underage daughters or sons pour the water onto the guests’ hands. As a sign of special respect, the host himself brings water for honoured guests.

Class distinctions are at work here. If a high-ranking aristocrat visits a person of a lower class, the householder himself brings the water for him to wash his hands.

“The householder should start eating before everyone else and stop eating after everyone else. Before starting to eat, they pronounce Allah’s name and say “bismillah”. If different courses are brought to the table, Allah’s name is mentioned separately every time” A visitor was considered to be a guest from Allah. This was widely acknowledged in Azerbaijan. For example, when asked “Do you want a guest from Allah?” a householder replied “May I be the sacrifice for both Allah and his guest”. The guest, too, knew that he would never be rejected; he could arrive uninvited and would not hear any protest. Thus he could knock on the door of any house.

Seeing the guest off in a proper manner made the host feel comfortable and experience inner satisfaction. Over the centuries, children were brought up in families in a spirit of respect for guests and this feeling was instilled in them time and again. It could not actually be otherwise, because in the future the guest would extol the good name of the family (after leaving their house).

Regardless of the aim of the visit, it is characteristic of hospitality to get together, share in someone’s joy and have a good time. There is always a hero of the occasion at such events, and at banquets a toastmaster is selected who congratulates the hero of the occasion on behalf of all participants and then glasses are raised to the health of all.

The wisdom of the ages

Hospitality is deeply rooted in people’s lifestyles. From ancient times people have visited each other and considered it their duty to offer help with building houses or other work in their community and also at wedding parties. Even after a house was built, it was a rule to invite people to celebrate.

Wise proverbs that have passed from generation to generation and travelled across the centuries have this to say about the guest and the respect due to him:

- A guest brings prosperity.

-A hospitable person’s table is never empty.

- A guest decorates one’s house.

- A guest is a flower of the house.

- May I be a sacrifice for the guest and for the road which brought him.

- The food for a guest comes before the guest himself arrives.

- A house without a guest is like a mill without water.

- The guest’s job is to come and the householder’s job is to host him.

In the modern period, hospitality is still especially important on a number of occasions. This can be seen during birthday parties, and match-making, engagement and wedding ceremonies. Congratulating someone on their birthday became fashionable. One of the customs is to give presents to the birthday person.

Hospitality involves ancient folk customs and is a widespread, long-lived rite that embraces certain of our people’s traditions and has preserved them to date.

Everybody knows that traditions of hospitality evolved gradually, passed from generation to generation and they have developed. The characteristic features of hospitality make people forget about their grief at weddings, celebrations and other festivities and inspire joy in the celebrants.

Hospitality has been adjusted to modern times and has undergone qualitative changes. The only feature that has not changed with time is the great respect for a guest. Customs and traditions are an indestructible bridge between generations. Historical upheavals and ruthless conquests have not been able to destroy this treasury of trust.

About the author Shirin Bunyadova is a Doctor of Historical Science, Member of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the Azerbaijani National Academy of Sciences and lecturer at Baku State University. She has written four books and a number of articles on Azerbaijan’s historical ethnography (12th-16th centuries) and hospitality.

by Shirin Bunyadova

Knock on any door...

Azerbaijan’s customs of hospitality are very revealing of the culture and the spirit of the world in which its people live. These customs tell us much about the people who live in this land and their potential. Alexandre Dumas wrote about Azerbaijani hospitality and also of the Caucasus peoples: “If you knock on any door in Azerbaijan, or anywhere in the Caucasus, say that you’re a foreigner and have no place to spend the night, the owner of the house will immediately give you his largest room. He and his family will move to the small room. Moreover, during the week, two weeks, or the month that you stay in his house he will take care of you and will not let you want for anything”.

Azerbaijanis consider it a duty to show infinite respect for a guest. The guest is sacred in Azerbaijan and the tradition of respect is taken very seriously.

The great 12th century Azerbaijani poet Nizami Ganjavi returned often to the noble custom of hospitality in his works. He wrote in his work “Yeddi Gozel” (The Seven Beauties):

She was welcoming as a garden flower,

Her smile was the bud of a rose.

Her palace was prepared for guests

And it reached to the skies

She laid a table and arranged a celebration,

Her servants were raised in grace.

For each new arrival, they held his horse’s bridle,

They laid the table according to rule.

They showed him courteous hospitality,

And dined him according to his rank.

In Nizami Ganjavi’s writings, hospitality is clearly seen as a custom routine in the everyday life of the Azerbaijani people.

Every household in Azerbaijan (within their means, sometimes even beyond their economic means) believed it their duty and a matter of honour to receive their guest with great respect, entertain him and send him on his way. This was not a tradition restricted to acquaintances only. It also applied to strangers, people who did not know each other at all and travellers on a journey.

In Azerbaijan hospitality acquired a certain status, took on a moral quality and became an internal instinct.

That is to say, regardless of whether the guest was personally invited or whether the householder knew him, everyone regarded a visitor to their country as their personal guest and felt bound to receive him and see him off sincerely. This is a distinctive feature of our people. The custom of hospitality seems simple enough, but it has specific requirements and can be quite demanding. Thus, it takes much effort and attention on the part of the householder to do the job thoroughly of receiving a guest, hosting him and seeing him off appropriately.

Guest: first and foremost

Even if an enemy steps into one’s house in Azerbaijan, no retribution may be exacted; as a guest he is untouchable. Eastern hospitality rises above all other customs of everyday life.

The householder would even set a guard to protect a guest whose life was in danger and who asked for help; as well as providing comfort, the safety of a guest was all part of the responsibility. This extended, of course, to protection of the guest’s belongings. All household members saw the guest off,

Miniature showing Khagan receiving Iskender as a guest, Nizami’s ‘Iskendername’ (Isfahan, 1560-1570)

Miniature showing Khagan receiving Iskender as a guest, Nizami’s ‘Iskendername’ (Isfahan, 1560-1570) As a mark of respect, the householder followed the departing guest with his eyes until he was out of sight. However, if the guest had a request or a wish when he was leaving the house, naturally, the host did his best to fulfil it and, if need be, he would expect to walk the guest to a staging post or take him to his destination.

There is a tradition in Azerbaijan that if a passer-by, even a complete stranger, says that he is a guest, a householder must serve him with all his heart and soul. Often, not only the house owner but also his relatives, consider it their duty to invite the guest to their place.

All household members were prepared for the sudden arrival of a guest. One or two extra portions of every meal would be prepared for just such an eventuality. In the past, a group of horsemen would meet high-level guests. Foreign guests were the centre of special attention and all influential people in the locality would call and invite them to their homes.

Azerbaijani households kept either a separate building or a room in the house as a guest room. Children were not allowed in there. If the visitor had a horse, even this was allocated a special place and well looked after.

In general, it was thought improper for the host to tire a guest with many questions, to ask why he had arrived or when he would leave. Only after the newcomer had said who he was and announced his purpose would the household rally round to provide all he needed.

Guests were freely given food, a room and a bed.

Each household member had a specific responsibility for the guest. The householder always ensured there were reserves of food and provisions.

Lay a good table...

From the earliest of times, a banquet would be held to honour a visitor, the table was laid and festivities began.

The guest was placed at the head of the table. Next to him sat the elder of the house, then other respected elders and people. Only adults could engage in conversation. It was not thought right to talk too much at the table during banquets and all had to know their place. The host also arranged for a selection of meals to appear on his banquet table.

The table on such occasions was laden with more delicious and abundant meals than for the everyday meal. The drinks served were sherbet and ayran (a diluted yoghurt drink – ed.) and, in some cases, wine. The meals served at a banquet table were mainly of rice and meat, accompanied by herbs. Along with different types of sweetmeats, jams etc., fruit was also served as dessert.

As a rule, banquets were accompanied by music – as confirmed by miniature paintings, which indicate that a special corner was set aside for musicians. For the sound to carry, the musicians would sing on the lower floor of a house, or from some distance within a tent.

Tradition decreed that it was impolite not to listen to the music at banquets, to ignore it or to talk a lot.

A common part of traditional hospitality was to give presents to the guest. The guest would offer a gift to the host and, in turn, the householder would send the guest off with other presents. This custom has survived to the present day.

The celebrated 17th century Turkish traveller and geographer Evliya Celebi described his reception in Azerbaijan, the banquet table and the presents given to guests: “During the banquet, a kalamkari (hand-printed – ed.) tablecloth was laid. Eleven types of plov (pilaf – ed.) were served: and soup, we ate tasty meals and had good conversation.

After the banquet, the guest, I and small Hasanagaya were given fine lynx leather. From there we went down to our tent. He sent us about 50 sheep, some 1,000 loaves of white bread, seven to eight mules of fruit and sherbet. That night we had a huge celebration; we stayed another two days there and had a look at the beautiful palaces on the bank of the river Qarsi.”

According to tradition, a man’s best quality is generosity, demonstrated by his ability to lay a good table and give a banquet for visitors to his house. People say that a generous person’s prosperity comes from Allah.

Guest for one, guest for all

When the householder is unable to provide a good reception for a guest, people help him. At this time, relatives and neighbours will help poor families. Thus hospitality goes beyond the limited framework of a household and becomes a collective effort. Good relations can be formed by benevolence and lending each other a helping hand is accepted as a moral law and the most honourable thing to do.

According to a folk custom, after receiving the guest it is advisable to leave him by himself for some time to rest, adjust and make himself comfortable. However, this should not be for too long, because one should not be inattentive to one’s guest. If the guest is a stranger and his stay is temporary, the house owner will not think it right to stay too long by his side, so as not to tire him.

The time of arrival also helps determine the rules. Thus, if the guest arrives in the evening, he is given food and a bed made up quickly. If the guest is someone close, an acquaintance or a relative, in this case the house owner naturally prefers greater contact. In this case, not only the house owner but also his relatives assemble and entertain the guest and fulfil the smallest of his wishes with enthusiasm. The guest becomes one of the family.

Since travellers were often not familiar with the country and the roads, naturally, as a sign of special attention to and care for travellers, they were given guides to enable them to continue their journey in comfort. The guide would not restrict himself to merely accompanying the guest on their journey but he would arrange meals and help with other things, too.

Decorating the guest house or room was by no means a formality. The interior of the house or guest room was decorated in the best taste. During the guest’s stay, everything in there was his. This meant that every single item in the room was for the guest’s use and at his disposal.

Hospitality during holidays is special. It is still a tradition, a duty and a good deed to invite a guest for a meal to break the fast during Ramazan, or to visit others to take them sweets and, during the Festival of Sacrifice (the Gurban Bayram holiday – ed.) to take some sacrificial meat (usually lamb) to close relatives and neighbours.

Thus, along with abstaining from food during these holidays, giving an evening meal to those fasting during the day and distributing the meat of sacrificial animals brings people closer together. The Novruz holiday is a particular time for visiting, when people settle quarrels and hand out presents and sweets.

Historically hospitable

The 17th century Dutch traveller Jan Struys, who attended Novruz holiday ceremonies, wrote of dashing in the company of aristocrats to eat now in one Azerbaijani’s place and now in another’s.

Visitors from various countries to Azerbaijan normally commented in their reports about how the local population received them and saw them off. This confirms once again the high level of hospitality in Azerbaijan. The 16th century Venetian Michele Membre often visited the houses of people that Shah Tahmasib made responsible for him in Tabriz. He noted that “all these people were pleased to talk to me, freely took me to their homes and sometimes allowed me to stay there for 15 to 20 days. They are pleased to hear about developments in Europe because they do not know anything about these countries....Their meals are similar to those of Turks but they are more generous and open-hearted and they give people food at their homes more often than the Ottomans do.” This indicates the hospitality developed over the centuries and is characteristic of our people. The primary indicator of hospitality is the laying of the table and its adornment with many dishes. This is the breaking of bread and sharing it equally with someone else.

The 15th century Venetian ambassador Ambrogio Contarini was greeted with gifts on his arrival in Isfahan. He writes with enthusiasm about the hospitality with which Uzun Hasan received him and Giosafat Barbaro, whom he invited to his palace in Isfahan in November 1474: “when we entered the room, we saw the shah surrounded by his courtiers.

According to the local custom, I bowed my head and he gestured that I sit on the carpet. Afterwards, we were served various delicious dishes cooked according to local custom. Then we parted. He invited us again. He kindly showed us his palace built on the bank of a river. Here, too, he treated us to different kinds of sweets.

Uzun Hasan invited us round often. Sometimes, we happened to eat in his marquee. The meals which came in bowls were served in large helpings and they were excellent. When we were not near Uzun Hasan, he often sent us various consumer goods. I was also quickly provided with a house.”

Anthony Jenkinson also wrote about the high level of hospitality in Azerbaijan. An English merchant and sailor, Jenkinson embarked upon a major sea journey in the 16th century and visited Azerbaijani territory. In his memoirs, he also provides information about the custom of hospitality here.

Thus he notes that he was sincerely and very well received when he was a guest of Abdulla khan in Shemakha. He writes about how he was invited to lunch. As a sign of respect, he was shown to a seat near the host. He notes that an expensive carpet was laid on the floor and that people were sitting on the floor with their legs folded. “When they saw that I was not used to sitting like that, a table was specially brought for me. A tablecloth was laid and various dishes were brought. There were about 140 of them. When they were removed, in its stead they laid a table full of fruit and adorned with other meals (there were about 150 of these). I was bid ‘welcome’ there. The next day, I was invited to go hunting. The hunting was fun. Upon our return, they presented me with long garments sewn according to their tradition; they put the garments on me and took me to the khan. I kissed his hand. Then, he seated me next to himself and we had lunch together. During the conversation, he inquired about how the hunting had gone. Upon my return, he gave me an excellent horse as a gift. He even gave me a guide and a watchman for the continuation of my journey. Finally, when we got to Ardebil, we were placed in a caravanserai built from white stone and designed for foreigners and other travellers. Everyone here is provided with food and feed for the horses.”

Home stays and caravanserais

There was a separate building for guests in the courtyards of rich and wealthy people. They were normally built in a convenient part of a common courtyard. This was especially important in places with no caravanserais (mainly in mountainous regions and villages). The construction of a separate house for guests indicates the importance of hospitality in our country. They were built with particular attention to their appearance, beauty and comfort as a reflection of both the house owner’s taste and his respect for a guest. The decoration of the house or the room allocated to the guest was meant to ensure his comfort and complete freedom: carpets were a special feature. In addition, there was bedding and sometimes even a musical instrument. The householder bore great responsibility for the guest but, at the same time, the guest’s presentation and manners were also important. Acting in line with the rules of propriety, maintaining self-control and behaving according to the customs of the alien environment he was in were the guest’s responsibilities. The guest was absolutely not expected to interfere in the family’s internal affairs or intervene inappropriately.

Like many oriental countries, Azerbaijan also had caravanserais. They were located in towns and on important commercially significant routes and were widespread in their capacity as hotels. There were more of them in large trading centres. There was a certain similarity in the construction of caravanserais in all areas of Azerbaijan. Along with rooms for relaxation, caravanserais also had a canteen, mangers, storage facilities, shops etc.

Home-style caravanserais, which were places of temporary shelter, usually served guests arriving in Azerbaijani territory. Most of the travellers and merchants who visited Azerbaijan at various times and travelled through the country spoke of the presence of such caravanserais and remarked on their interior and exterior appearance.

Cleanliness next to...

In Azerbaijan, too, as in a number of Muslims countries, Shari’ah rules applied and this was directly evident as regards hospitality. For example, according to Shari’ah, “hands should be washed and wiped with a towel before and after eating”.

Also, unlike in the West, guests in the Muslim East did not retreat to a special room or corner to wash their hands. Water in an elegant container, and a bowl, were brought to guests at the table. The guests washed their hands without leaving their places.

This is how hands should be washed according to the etiquette: after the first of the guests washes his hands, next is the one sitting to his right. Thus, all of them take turns to wash their hands. After they have eaten, a parch (a type of metal jug – ed.) and a bowl are also brought. The guest who was last to wash his hands before eating is the first to wash his hands after eating. As a rule, a servant or the host’s underage daughters or sons pour the water onto the guests’ hands. As a sign of special respect, the host himself brings water for honoured guests.

Class distinctions are at work here. If a high-ranking aristocrat visits a person of a lower class, the householder himself brings the water for him to wash his hands.

“The householder should start eating before everyone else and stop eating after everyone else. Before starting to eat, they pronounce Allah’s name and say “bismillah”. If different courses are brought to the table, Allah’s name is mentioned separately every time” A visitor was considered to be a guest from Allah. This was widely acknowledged in Azerbaijan. For example, when asked “Do you want a guest from Allah?” a householder replied “May I be the sacrifice for both Allah and his guest”. The guest, too, knew that he would never be rejected; he could arrive uninvited and would not hear any protest. Thus he could knock on the door of any house.

Seeing the guest off in a proper manner made the host feel comfortable and experience inner satisfaction. Over the centuries, children were brought up in families in a spirit of respect for guests and this feeling was instilled in them time and again. It could not actually be otherwise, because in the future the guest would extol the good name of the family (after leaving their house).

Regardless of the aim of the visit, it is characteristic of hospitality to get together, share in someone’s joy and have a good time. There is always a hero of the occasion at such events, and at banquets a toastmaster is selected who congratulates the hero of the occasion on behalf of all participants and then glasses are raised to the health of all.

The wisdom of the ages

Hospitality is deeply rooted in people’s lifestyles. From ancient times people have visited each other and considered it their duty to offer help with building houses or other work in their community and also at wedding parties. Even after a house was built, it was a rule to invite people to celebrate.

Wise proverbs that have passed from generation to generation and travelled across the centuries have this to say about the guest and the respect due to him:

- A guest brings prosperity.

-A hospitable person’s table is never empty.

- A guest decorates one’s house.

- A guest is a flower of the house.

- May I be a sacrifice for the guest and for the road which brought him.

- The food for a guest comes before the guest himself arrives.

- A house without a guest is like a mill without water.

- The guest’s job is to come and the householder’s job is to host him.

In the modern period, hospitality is still especially important on a number of occasions. This can be seen during birthday parties, and match-making, engagement and wedding ceremonies. Congratulating someone on their birthday became fashionable. One of the customs is to give presents to the birthday person.

Hospitality involves ancient folk customs and is a widespread, long-lived rite that embraces certain of our people’s traditions and has preserved them to date.

Everybody knows that traditions of hospitality evolved gradually, passed from generation to generation and they have developed. The characteristic features of hospitality make people forget about their grief at weddings, celebrations and other festivities and inspire joy in the celebrants.

Hospitality has been adjusted to modern times and has undergone qualitative changes. The only feature that has not changed with time is the great respect for a guest. Customs and traditions are an indestructible bridge between generations. Historical upheavals and ruthless conquests have not been able to destroy this treasury of trust.

About the author Shirin Bunyadova is a Doctor of Historical Science, Member of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the Azerbaijani National Academy of Sciences and lecturer at Baku State University. She has written four books and a number of articles on Azerbaijan’s historical ethnography (12th-16th centuries) and hospitality.

.jpg)