Azerbaijan was a major area of silk farming in the Soviet Union, alongside Ukraine and Uzbekistan, and following a post-Soviet dip and unpredictable oil prices, the Azerbaijani government is now striving to revive the industry. In this article, however, we revert to the Soviet past and explore the Azerbaijani sericulture industry through a recently unearthed family photo album.

I spent my early childhood mostly at my grandmother Aida Ismailova’s home. More so than the time at my parents’ home, my grandmother’s house and the times I spent with her were carved into my mind as childhood memories. My favourite activities at my grandmother’s house were painting with watercolours, eating pasta, riding my big blue bicycle and watching television programmes in the evenings with my grandmother. One entertainment I was allowed from time to time was looking at photo albums and greeting cards written by various people.

Perhaps I saw these photos many times, but as a child these monochrome prints were not interesting to me

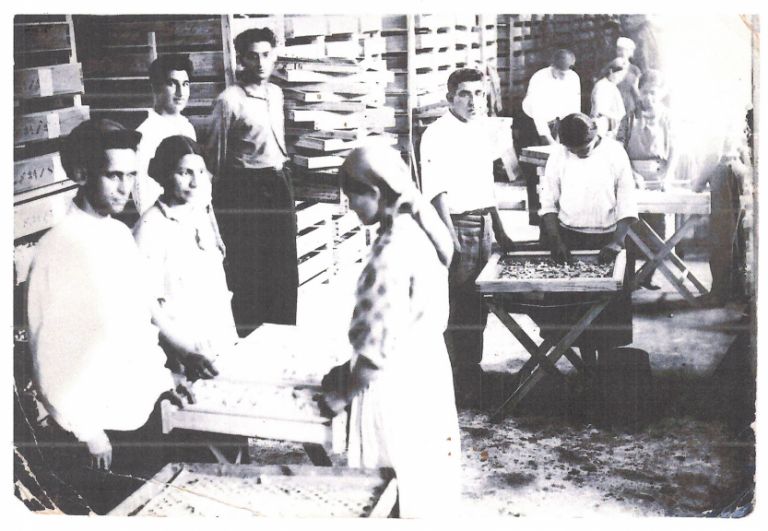

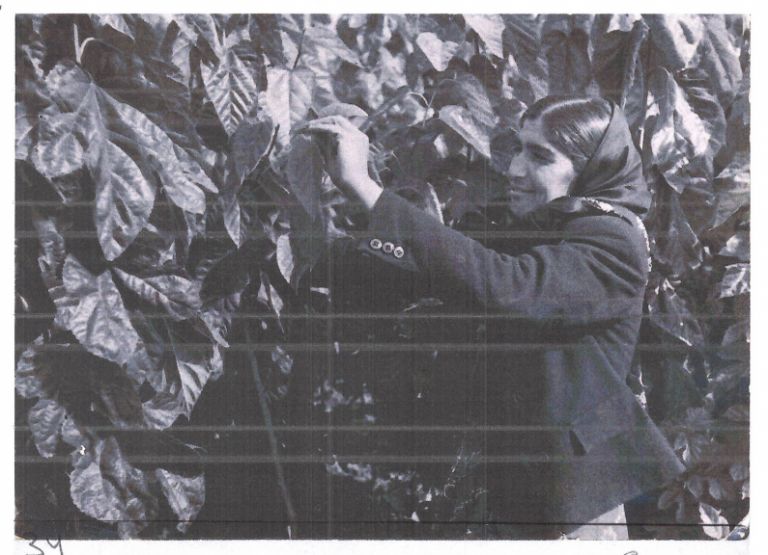

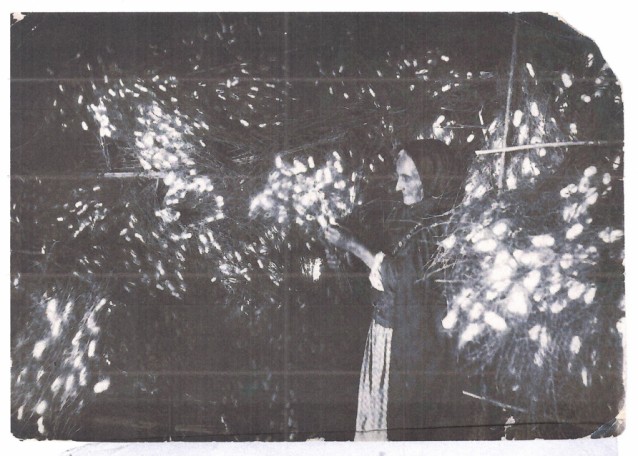

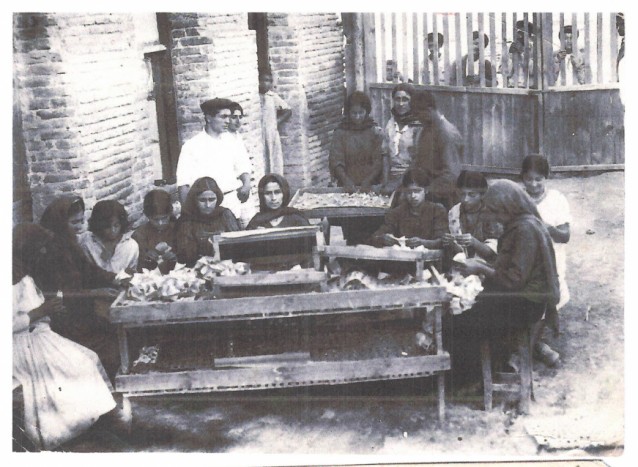

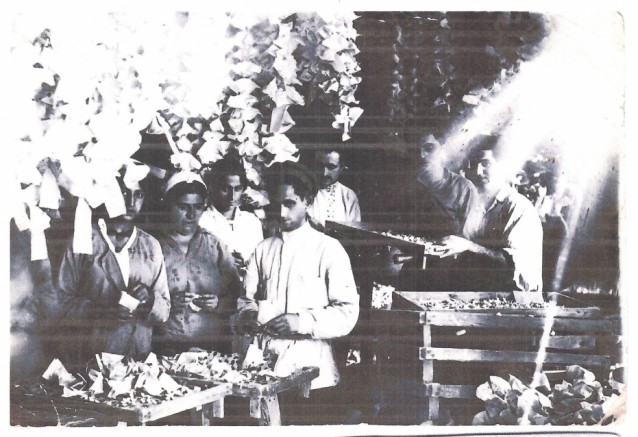

There were black-and-white photos depicting women with scarves on their heads against a background of mulberry trees and white-gowned factory workers who for reasons unknown to me were folding paper and hanging it from a pan. Perhaps I saw these photos many times, but as a child these monochrome prints were not interesting to me and I just flipped through them.

Life has a bitter irony – at the time when our grandparents have plenty to tell us we are less likely to listen and understand them, and then once we have grown up we have so many questions for our aging grandparents as we explore our roots, but by then they cannot answer us. Either their memory has weakened and broken down completely, or they are no longer in the same world as us.

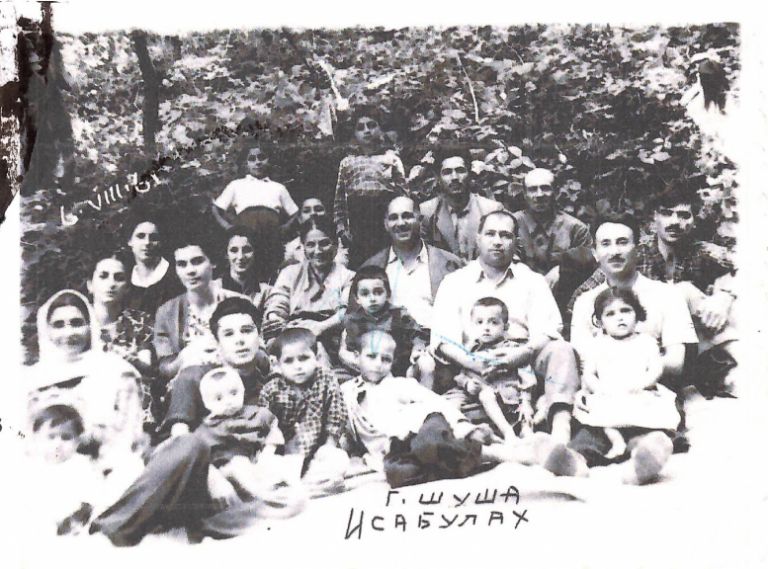

Some time ago I took out my grandmother’s album to find photos of my ancestors for my son’s school project. That was how I found the archive of my grandmother Aida’s parents, Siddiga Afandiyeva and Isa Ismailov. My great-grandmother Siddiga was originally from Sheki and my great-grandfather Isa was from Lanberan (presently part of Barda).

They met while they were studying in Ganja at the Azerbaijan Agricultural Institute and married soon after. Initially, my great-grandfather worked in Quba in line with his profession and later both of them were appointed to work in their area of expertise at the Aghdam silkworm breeding plant.

Sericulture in the USSR

In the history of sericulture, the first large silkworm breeding enterprises were established in the Soviet Union, where sericulture was most developed in Uzbekistan, Ukraine and Azerbaijan. The largest silkworm breeding plant in the South Caucasus began functioning in Sheki in 1931. Another factory in Ordubad functioned in the 1960s and 1970s, when, according to Azernews, Azerbaijan was producing some 7,800 tonnes of raw cocoon annually. The raw silk was used in light industry, in the military to produce parachutes and explosives and in medicine to produce surgical thread.

In Azerbaijan at that time there were seven grainages breeding silkworms and 80 factories collecting and processing the cocoons. Grainages (from the French word “grainage”) were called “Grenzavod” in the USSR for short. The function of these plants was to obtain healthy silkworm larvae by fighting communicable diseases that can infect silkworm larvae. The purebred silkworm larvae they produced were sent to an affiliated sericulture enterprise for feeding and breeding. The mature silkworms bred by these enterprises spun cocoons, which were then delivered back to the grainage factories.

From 1936 the Aghdam grainage plant where my great-grandfather worked was supplied its silkworm products by the Tractor collective farm in the Stepanakert (Khankendi) region of Nagorno-Karabakh. The Aghdam farm developed the yellow “ascoli” and “oro” larvae breeds. Elsewhere in Karabakh, 80 people worked in silkworm breeding at the Avant-garde collective farm in the Gadrut region.

In the Soviet Union, the cellular method was used to produce healthy larvae. In this method, after the fertilization of moths, the female moths were placed into paper bags in which they produced larvae. Then the moths were checked for infection with a microscope. The infected moths were disposed of together with their larvae while the larvae produced by healthy moths were collected, washed and placed again in paper bags of 25-29 grams each. These bags were hung and stored in a cold place until the following spring.

As production developed, mulberry gardens were planted to feed the silkworms in 15 regions of Azerbaijan, including Shamakhi, Ganja, Sheki, Zaqatala, Aghdash, Qakh and Qabala.The advantage of the mulberry silkworm, obtained by genetic methods, was that the females could only produce high-quality male larvae, and the male silkworms in turn produced cocoons with more silk fibre. Another type of silkworm, the oak silkworm, was first brought to the Soviet Union from China in 1937. Silk fibres made by this type are coarser and stronger than those made by the mulberry silkworm, but since oak silkworms were not beneficial from an economic point of view, the Soviet Union stopped breeding them. Prior to that, however, in 1938 the Telman collective farm in Qusar achieved great success in oak silkworm breeding.

Other noteworthy collective farms in the Soviet Azerbaijani sericulture industry were the Lenin, Yukhari Sovet and Qizil Azerbaijan collective farms in the Aghdash region, and the Qizil Oktyabr collective farm in the Goychay region. Selection work (to obtain highly productive breeds) was mainly conducted by the Central Asian Scientific Research Institute of Sericulture in Tashkent, the Azerbaijan Scientific Research Institute of Sericulture in Ganja and the Georgia Agricultural Institute.

Silk RevivalA presidential decree signed in late November 2017 aims to resurrect the country’s once thriving sericulture industry, which almost ground to a complete halt after the fall of the USSR when state funding ceased and collective farms fell apart. In 2015 the country produced just 236 kg of raw cocoon. The following year it rose to approximately 70 tonnes and 2017 saw 245 tonnes. The Azerbaijani government is reportedly seeking to increase this figure to 6,000 tonnes of raw cocoon by 2026. |

Lives interrupted

During World War II, my great-grandparents had to stop working in sericulture. My great-grandfather went to war. My great-grandmother worked as a teacher in Barda on the eve of the war and then moved to Zaqatala.

During the war, the family received death notices informing them that great-grandfather Isa and his brother had been killed. The mourning ceremony for both brothers was held in Lanberan. But one year after the end of the war my great-grandfather, alive, returned to his family. It appears that he was held captive for a while, and then was forced to marry a German widow and even had a son by her. After the war my great-grandfather decided to return from Germany to the Soviet Union to his dear wife and four children.

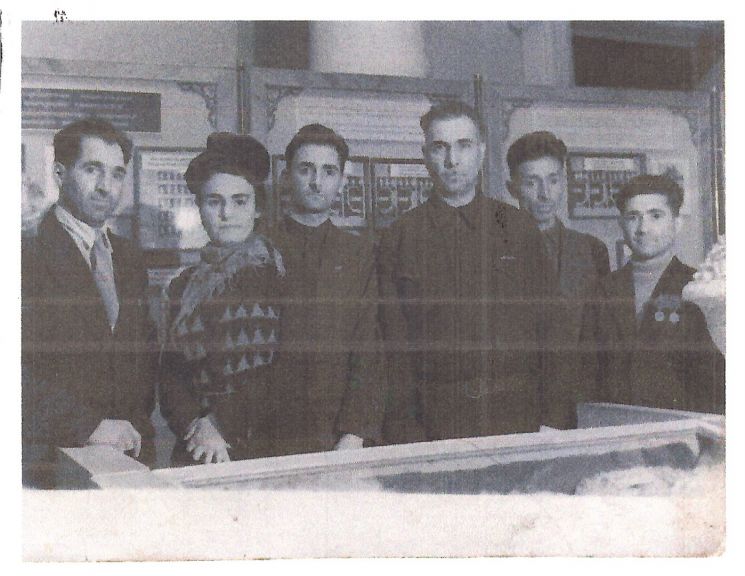

Once peace had been restored, my great-grandparents returned to their previous professions. As far as I know Isa Ismailov worked as a director of the Aghdam Grainage Factory and Siddiga Afandiyeva worked as a chief agronomist for many years. The photos I discovered were most likely intended to show the technology of the equipment and the organisation of the farm for an exhibition or event.

The most prominent emotion I feel is pride

For me these photographs bring up a strange mixture of emotions. I did not know my great-grandmother and great-grandfather in person, so I have a sense of distance. But from another perspective, I carry my closeness to my great-grandparents in my blood, so I also feel a familiarity. Being able to look at these photos today is the heritage they left me. Thanks to these photos, I have a detailed explanation of their lives’ work, which they did with such love. The most prominent emotion I feel is pride. It is a great honour for me to share the success story of these people who played a role in the development of sericulture in Azerbaijan.

About the author: Saltanat Zulfugarova holds an MA in Environmental Sciences and is an author of children’s books.