Marking the 135th anniversary of the Caspian-Black Sea Oil Industry and Trade Company (1883-2018)

The Rothschild brothers, co-owners of the Rothschild Brothers Banking House in Paris, began taking an interest in Russian oil fields in the late 1870s. However, the official registration of their firm, the Caspian-Black Sea Oil Industry and Trade Company (hereafter shortened to “the Caspian-Black Sea Company”), didn’t take place until 16 May 1883, on the basis of the bankrupt Batumi Oil Industry and Trade Company. The brothers chose to focus mainly on the foreign market and by the end of the 1880s had already become the leading exporters of Russian kerosene.

Alongside the Nobel brothers, the Rothschild brothers’ Caspian-Black Sea Company became one of the leading oil companies in the Russian oil business in the late 1880s

Kerosene kings

Since its very establishment, the company was very active, buying up kerosene from 135 small and medium-sized companies on mutually advantageous terms for shipment to various regions of Russia and abroad. The Rothschilds concluded contracts for the commission sale of kerosene on a preferential basis for enterprises, which ultimately led to the following: whereas in 1884 company exports of oil products from Baku was 2.4 million poods (one pood is approximately 16.38 kg - Ed.), in a matter of five years this figure reached 30 million poods. The first test for the Rothschilds was to transport the kerosene from Baku to Antwerp on the Ferguson oil steamer. Then they began shipping the kerosene to London as well.

With six million gold roubles and 25 million francs of initial capital in Russian safes, the Rothschilds began business with their characteristic energy. But the Caspian-Black Sea Company also owed its success to the ties the Rothschilds established in the upper echelons of the Russian government (as the Nobels had prior to them). Alongside the Nobel brothers, the Rothschild brothers’ Caspian-Black Sea Company became one of the leading oil companies in the Russian oil business in the late 1880s.

For a long time, the chief engineer of the Rothschilds’ oil industry in Baku was David Landau, father of the 1962 Nobel Prize winner in physics and native of Baku, Lev Landau. One of the company’s managers was the well-known chemist Adolf Gukhman (1866-1914), a member of the board of the Baku branch of the Imperial Russian Technical Association (BB IRTA). The company’s founder was Baron Alphonse Rothschild (1827-1905), who headed the Paris Banking House in 1868 and was the son of famous banker James Rothschild (1792-1868).

Through Alphonse Rothschild, the tsarist government issued a series of loans in France. In particular, the construction of the Transcaucasian Railway linking Baku with Batum was completed in 1883 thanks to a loan granted by Alphonse Rothschild. As a result, he gained the right to preferential ownership of Baku oil enterprises. In 1884 alone, about 5.6 million poods of various petroleum products were transported by the Transcaucasian Railway, which opened the door for Russian oil to the West and marked the beginning of a brutal and sustained (about 30-year) struggle for world oil markets which in fact continues to this day.

When the Rothschilds’ Caspian-Black Sea Company received permission to install its own tank wagons on the Transcaucasian Railway, the available number of 600 wagons was clearly insufficient to meet demand. Therefore, the company supplied a further 300 tank wagons in 1887 and lent capital (two million roubles) to many smaller companies to install an additional 1,500 tank wagons on the condition of repayment within five years with an annual interest rate of six per cent. This led to the fact that as early as December 1888, of the 3,932 wagons with kerosene shipped from Baku, the Rothschilds’ firm received 1,800 in Batum (renamed Batumi in 1936). By the end of the 19th century, major oil companies of the Nobel brothers, Rothschilds, Shibayev, Unanov and others had the largest number of tank wagons on the Transcaucasian, Gryaz-Tsaritsyn and other railways of Russia.

After the death of Alphonse in 1905, his younger brother, Baron Edmond, dealt directly with Russian oil affairs. Another key figure in the oil business was the chief engineer of the Paris Rothschild Brothers House, George Aron, who managed the oil companies on site as well as the export and sale of oil and petroleum products.

The board of the Caspian-Black Sea Company consisted of three directors – Moris Efrusi (Alphonse Rothschild’s son-in-law), Prince A. G. Gruzinsky and Arnold Feigl, who was in charge of all the firm’s preliminary and preparatory work.

in 1888 kerosene exports by the Rothschilds’ company exceeded 16 million poods, accounting for 58.6 per cent of all Russian exports

At home and abroad

Alphonse Rothschild’s company pioneered the unification of the Russian export trade by starting, in 1887, along with the export of its own products, the commission sale of kerosene belonging to 40-50 other Russian oil producers. As a result, in 1888 kerosene exports by the Rothschilds’ company exceeded 16 million poods, accounting for 58.6 per cent of all Russian exports. In fact, the Rothschilds’ own enterprises produced only 2.5 million poods; in other words, according to an 1888 issue of the newspaper Kaspiy, what had formed was, a sort of syndicate concentrating more than half of kerosene exports from Russia in its hands.

The abolition of the repurchase system in Russia at the end of 1872 had led to an unprecedented growth in the number of refineries; by 1893, there were 69 plants in the Baku oil district alone.

Nonetheless, at the end of the 19th century, the concentration of production intensified in the Russian oil industry, which is evidenced by the following figures: only the seven largest factories, accounting for about 10 per cent of all the factories in the empire, contributed 68 per cent of the total kerosene production (22.5 million poods). These factories belonged to the Nobel brothers – 10.7 million; the Caspian Association – 3.5 million; Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev – 2.4 million; the Baku Oil Company – 1.7 million; Alphonse Rothschild – 1.5 million; Musa Naghiyev – 1.5 million; and Shamsi Asadullayev – 1.2 million poods.

In 1890, just 13 factories (about nine per cent of the total number of plants) produced three quarters of the total quantity of lighting oils (51 million poods), of which 17.9 million came from the Nobel brothers’ factory and 4.7 million from the Rothschilds’.

In an effort to conquer the domestic market, Alphonse Rothschild opened branch offices of the Caspian-Black Sea Company in cities of the Volga region: Nizhny Novgorod, Samara, Tsaritsyn, Astrakhan, and also in the Baltics – the so-called Riga reservoirs, in Belorussia – the Vitebsk reservoirs, and in Poland – the Warsaw reservoirs. The delivery of oil products to these regions was carried out by the Mazut trade and transport company established by Alphonse Rothschild in 1898. Subsequently, Mazut became one of the largest oil export associations, possessing 13 tankers in the Caspian Sea alone.

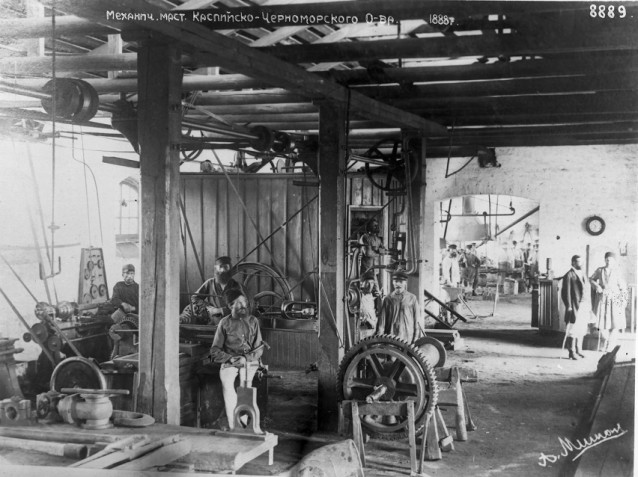

Mechanics workshop of the Caspian-Black Sea Society. Photo: Azerbaijan National Photo and Film Archive

Mechanics workshop of the Caspian-Black Sea Society. Photo: Azerbaijan National Photo and Film Archive

Since the Transcaucasian Railway couldn’t fully cope with the volume of oil and petroleum products, transport via the Caspian Sea was of particular importance. Ships were divided into categories depending on their shipowners. The repair of oil ships belonging to the Caspian fleet was carried out in Baku or Astrakhan, where most of the ship repair enterprises were located. By 1900, there were about 30 ship repair enterprises in the Astrakhan governate alone, the largest of which were owned by Caucasus and Mercury (237 workers), the Rothschilds’ Mazut (195 workers), the Eastern Society (176 workers) and the Nobel brothers (170 workers).

After the opening of the Transcaucasian Railway in 1883 and the establishment of direct links along the Caspian and the Volga, the idea to construct the Baku-Batumi pipeline was put forward. Among those that supported the initiative were Alphonse Rothschild and other oilmen including Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev, Musa Naghiyev, Ivan Ilimov, Alexander Benkendorf and S. Baghirov. Construction began in 1897 and when the pipeline came into operation in July 1907, it became a unique event in the empire’s oil industry. It was the longest (885 km) and best kerosene pipeline of the time, with an annual carrying capacity of 60 million poods.

Merging with the Nobels

In 1903, a cartel agreement was concluded between the Nobel brothers and the Mazut association according to which Emmanuel Nobel (son of Ludwig Nobel) and Alphonse Rothschild joined forces in exporting Russian kerosene to foreign markets. Already by the end of 1901, the Nobmazut cartel transported 43 per cent of fuel oil, 57 per cent of kerosene and 67 per cent of the technical oils extracted from Baku oil.

By pursuing a coordinated economic policy, Nobmazut successfully countered the other major player on the world’s kerosene market, the American syndicate Standard Oil, which was trying very hard to gain a footing in the Caucasus and Absheron oil markets. Standard Oil tried in every possible way to cooperate with the Rothschilds’ Caspian-Black Sea Company, but no deals that would contradict Russia’s interests ever took place, contrary to rumours circulating in the Russian press.

The establishment of Nobmazut provoked resistance from a number of competing firms, which in order to counter the Nobel-Rothschild agreement created the firm Tocamp in 1901 with financial support from the British. And had it not been for the consent received by Emanuel Nobel from British industrialists on the joint sale of kerosene in Germany, Tocamp might have become a strong rival for the Nobmazut cartel.

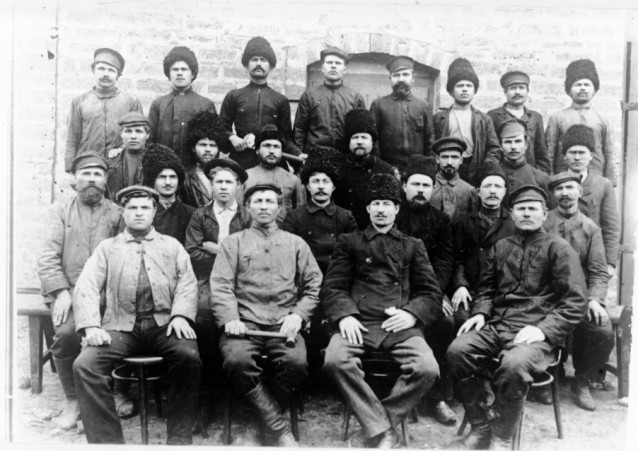

Workers of the Rothschilds’ Bibiheybat oil fields. Photo: Azerbaijan National Photo and Film Archive

Workers of the Rothschilds’ Bibiheybat oil fields. Photo: Azerbaijan National Photo and Film Archive

Later on, a group of several large and medium-sized oil companies (with a combined annual production of 150 million poods) formed an alliance which aimed to weaken Nobmazut’s mediation in the delivery of oil and petroleum products, as well as these two firms’ influence on price setting both in Baku and on foreign markets.

At the beginning of 1907, the Nobel-Rothschild cartel possessed warehouses in many regions of the Russian Empire. Naturally, the most extensive storage system for petroleum products was created in Baku: by 1900, there were about 2,000 different storage facilities with a total capacity of 276.5 million poods there. But there were also many warehouses located in the Volga cities. For example, there were oil depots with a total capacity of 35 million poods in Astrakhan in 1900. In Saratov, there were 46 metal tanks and a large number of earth pits to store oil products belonging to the Nobel brothers, the Rothschilds’ Mazut, the Eastern Society and the Ryazan-Ural railway. These had a total capacity of 20 million poods.

Most of the fuel oil reserves also belonged to the Nobel brothers and the Rothschilds. In particular, of 8.9 million poods of oil left in the warehouses of Nizhny Novgorod by April 1899, the Nobel brothers owned 2.96 million and Mazut owned 2.90 million poods, which constituted over 65 per cent.

Having monopolized oil production, Nobmazut started monopolizing kerosene production as well. By the end of 1907, the cartel accounted for 75 per cent of kerosene sales in the domestic markets of the Russian Empire. Under the skilled management of Emanuel Nobel and Edmond Rothschild, in 1909 the Nobmazut cartel accounted for 90 per cent of the gross sales of all oils produced in Baku, with all the other companies making up the remaining 10 per cent. The Nobmazut cartel also possessed a powerful oil fleet. For example, in 1913 it owned 72 of 160 oil barges on the Volga.

The cartel also controlled the London oil company Consolidated Petroleum Co., formed in August 1900 with a fixed capital of 500,000 pounds sterling and a competitor for American oil companies. Nobmazut was the only representative of British companies in international markets.

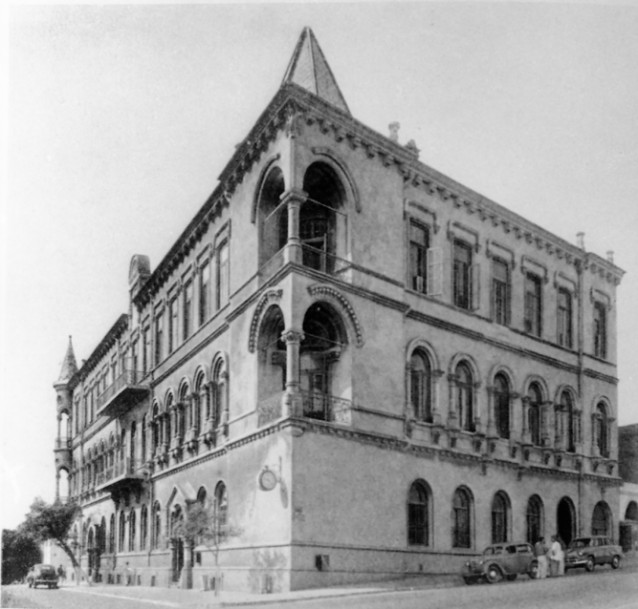

Building belonging to the Caspian-Black Sea Society in Baku. Photo: Azerbaijan National Photo and Film Archive

Building belonging to the Caspian-Black Sea Society in Baku. Photo: Azerbaijan National Photo and Film Archive

Ahead of the game

At a time when Russia had overtaken the USA in oil production, the distribution of oil production in June 1901 looked as follows: Nobel brothers – 5.7 million poods; the Caspian-Black Sea Company – 3.9 million poods; and the Baku Oil Society – 3.4 million poods.

The success of the Caspian-Black Sea Company was largely down to the reliable information it possessed. The Rothschilds received accurate data in Paris, St Petersburg and Baku based on economic and technical calculations. Their accurate knowledge of the oil business and ability to observe and promptly react to all changes in Russian oil production allowed them to firmly establish themselves on the Absheron (Baku), in the Caucasus (Grozny, Maykop, Batum) and in Turkmenistan (Cheleken).

For example, the relatively weak enterprises Russian Standard and Moscow Oil Industry Society, under the Rothschilds’ powerful patronage, conducted effective exploration and development of oil fields in Grozny, the Kuban region and in Maykop in 1902. As a result, the North Caucasus, previously known for being purely agricultural, became an oil region thanks to the activities of large firms, especially those of Alphonse Rothschild, Emanuel Nobel and I. Akhverdov.

In 1907, the Rothschilds subsidized and then established control over many oil companies through the Russian-Asian Bank: the Absheron Oil Company, having seized 40 per cent of its shares; Shikhovo; Melikov; the Russian Oil Society etc.

In 1910-1911, Edmund Rothschild acquired the majority of the shares in the Russian companies Neft (Oil) and G. M. Lianozov & Sons for approximately two million roubles. The shares of these companies were highly quoted on the Paris stock exchange. As a result, before the 1917 October Revolution, the Rothschilds owned over 35 per cent of the total share capital of 15 large enterprises of the Russian oil industry.

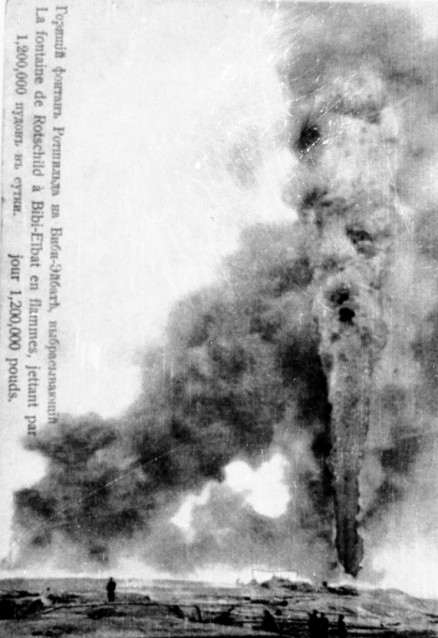

A burning fountain in the Rothschild’s oil field in Bibiheybat. Photo: Azerbaijan National Photo and Film Archive

A burning fountain in the Rothschild’s oil field in Bibiheybat. Photo: Azerbaijan National Photo and Film Archive

The nationalization of the Caspian-Black Sea Company and the Mazut association by a decree of the Baku Commune dated 2 June 1918 had no direct bearing on the Rothschilds because they had sold their Russian oil companies to the Anglo-Dutch Trust Royal Dutch Shell (the main rival of the American syndicate Standard Oil) in 1912, receiving in return 27.5 million roubles, as well as 20 per cent of the shares of the Shell trust in Paris. Already by 1913 British entrepreneurs had begun to take the lead in Russia’s oil business.

In other words, possessing reliable information about the impending start of World War One and several years before the October Revolution in Russia, the Rothschilds ceded their oil business to the British. Thus, the losses of these brothers (as opposed to the Nobel brothers) in revolutionary Russia were minimal and Edmund Rothschild (Alphonse’s successor in the banking business), who stopped lending money to the tsarist government as early as 1911, was regarded as the most prudent person in Europe.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the Rothschilds, like the Nobel brothers, were also engaged in charitable activities in Russia. Their enterprises provided compulsory insurance for workers who received significant cash benefits in the event of injury or illness. The reports of Mazut for 1908 indicate that 100,000 roubles were transferred to the insurance capital fund from the shareholders’ profit. The Oil and Bibi-Heybat Oil Society companies, which were also part of the Rothschilds’ oil group, replaced ordinary bonuses for workers with interests in the profits from the oil fields, thereby laying the foundation for “people’s capitalism.” Directors of Rothschild enterprises also acted as trustees of city schools and provided generous material assistance to Jewish communities in Russia.

On the basis of all this, overall the Rothschild brothers played an undeniably positive role in the accelerated development of the Russian (now Azerbaijani) oil business.

About the author: Mir-Yusif Mir-Babayev is a doctor of chemistry, a professor at the Azerbaijan Technical University and author of books on Azerbaijan’s oil history.